In the lead-up to the March 4, 2012 presidential vote, authorities have harassed a major election-monitoring nongovernmental organization, directly and indirectly interfered with the operation of independent news outlets critical of the government, and harassed and threatened civic activists.

(Human Rights Watch/IFEX) – Moscow, March 1, 2012 – Russian authorities are cracking down on government critics at the same time as they are tolerating large public protests, Human Rights Watch said today.

In the three months between the December 2011 parliamentary election and the March 4, 2012 presidential vote, the authorities have harassed a major election-monitoring nongovernmental organization, directly and indirectly interfered with the operation of independent news outlets critical of the government, and tried repeatedly in cities around the country to intimidate civic activists. Several activists have also been violently attacked by unidentified people.

“The Russian government has done the right thing by allowing unprecedented public protests and proposing some reforms,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “But the authorities are also trying in numerous ways to make their critics think twice about speaking out or protesting. Despite the positive developments, the climate for civil society is as hostile as it ever was.”

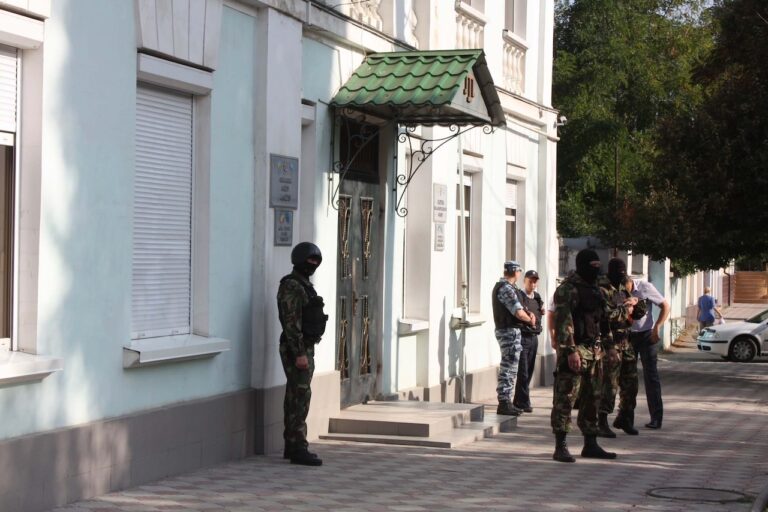

Interference with nongovernmental organizations and independent media outlets and their staff has included lawsuits, detention, and threats from state officials. State-controlled media have run articles that seek to discredit the protest movement, government critics, and the political opposition.

Civil society activists from several major Russian cities told Human Rights Watch that police officials had summoned them, and in some cases their family members, for questioning, during which they were either intimidated or overtly threatened. New regulations make it possible for websites to be shut down without a court order. Members of parliament have suggested new restrictions on nongovernmental organizations that receive foreign funding.

“I never had problems of this nature before – not until I got involved in political activism,” one activist told Human Rights Watch, describing an attack outside his apartment building that left him bruised and with a concussion. Another activist was forced into a car, threatened, and beaten up by men who told him they were from the Federal Security Service.

Already angered over President Dmitry Medvedev’s announcement in September that Prime Minister Vladimir Putin would seek another term as president, thousands took to the streets following the December 4 Duma elections to protest alleged election fraud. They also called for an end to government corruption, the release of political prisoners, and even Putin’s resignation. The unprecedented wave of protests continued throughout the winter in Moscow and several other major Russian cities.

Toward the end of December, Medvedev announced reforms aimed at political liberalization and increasing political pluralism. The reforms included restoring a system to regional governors, who under Putin had become political appointees, and simplifying registration for political parties. The Kremlin maintained that the reforms had been planned for some time instead of in response to the protests.

“Russia’s new president, whoever it is, needs to show he’s serious about reform by putting an end to the harassment of the very people who are advocating for it,” Williamson said.

(. . .)