Teams of government officials have inspected at least 30 civil society groups in the past two weeks in Moscow and many more in other regions of Russia.

A wave of inspections of nongovernmental organizations in Russia is intensifying pressure on civil society since the adoption of a series of restrictive laws in 2012, Amnesty International, Frontline Defenders, and Human Rights Watch said today. Teams of officials from a variety of government agencies have inspected at least 30 groups in the past two weeks in Moscow, and many more in at least 13 other regions of Russia.

The inspections appear to target groups that accept foreign funding and that engage in advocacy work, and are part of a broader crackdown on civil society that began in 2012, the organizations said. The Russian prosecutor’s office has stated publicly that it plans to inspect between 30 and 100 nongovernmental organizations in each of Russia’s regions, which could amount to thousands of groups throughout the country. According to media reports, the prosecutor’s office in St. Petersburg alone plans to inspect about 100 groups.

“The scale of the inspections is unprecedented and only serves to reinforce the menacing atmosphere for civil society,” said Hugh Williamson, Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The Russian authorities should end, rather than intensify, the crackdown that’s been under way for the past year.”

On March 21, 2013, five officials from the prosecutor’s office, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ministry of Justice, and the Tax Inspectorate arrived without warning at Memorial society, one of Russia’s most prominent nongovernmental groups, to conduct an inspection.

A television crew from NTV, a pro-Kremlin station, arrived with the inspectors to film the proceedings. It is not clear how NTV learned about the inspection since most government inspections in the current wave are unannounced.

Nevertheless, later that day, the station aired a news report alleging that Memorial may be in violation of the “foreign agents” law. In recent years, NTV has broadcast numerous shows seeking to portray Russia’s political opposition as foreign-sponsored.

“The foreign agents law was, from the start, aimed at demonizing advocacy groups in Russia,” Williamson said. “It’s distressing, but sadly unsurprising, that NTV is part of the effort to discredit independent voices.”

Also on, March 21, the prosecutor’s office inspected the offices of at least four other human rights organizations, all in St. Petersburg.

Pavel Chikov, head of Agora, a human rights group that provides advice about laws governing nongovernmental groups, said that the inspections are to determine whether groups are complying with a raft of regulatory laws.

The laws include one adopted in November that requires any group that accepts foreign funding and engages in “political activity” to register as a “foreign agent.”

“There has long been a fear that Russia’s new NGO law would be used to target prominent critical organizations,” said John Dalhuisen, Amnesty International’s Europe and Central Asia director.

“The spate of inspections in recent weeks appears to confirm this suspicion. The bigger fear is that this is just round one, and that, after the smearing, the forced closures will come.”

The “foreign agents” law was roundly criticized in Russia and abroad, including by the United Nations high commissioner for human rights and the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, of which Russia is a member.

For months after the law’s adoption it was not clear how and whether it would be enforced.

However, at a February 14 meeting with the Federal Security Service, President Vladimir Putin said, “We have a set of rules and regulations for NGOs in Russia, including rules and regulations about foreign funding. These laws, naturally, should be enforced. Any direct or indirect interference in our internal affairs, any form of pressure on Russia, on our allies and partners is inadmissible.”

In late February, the media began to report on inspections of nongovernmental groups by the prosecutor’s office in the Saratov region in southern Russia, and then on March 5, the wave of inspections began in Moscow.

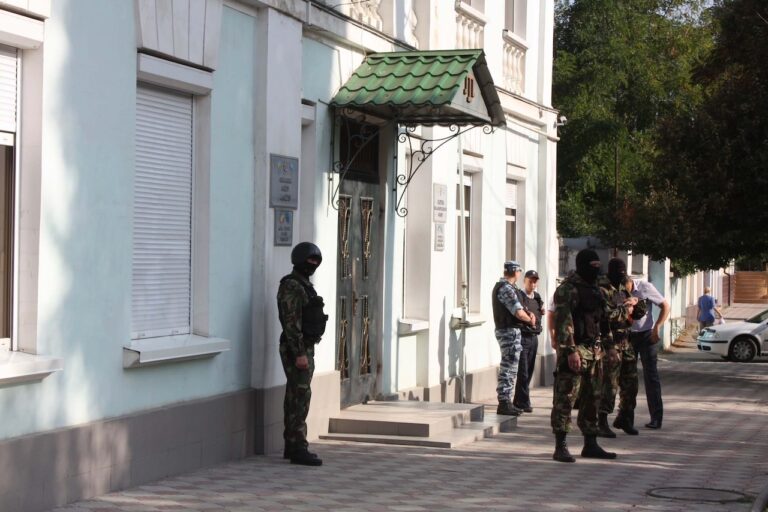

In most cases the inspections are carried out by a team of prosecutorial, Justice Ministry, and tax officials. In some cases the inspectors also examine whether a group’s work is “extremist,” in response to an alleged complaint filed by an individual or government agency. Some inspections have included agents from the Federal Security Service, fire department, sanitation department, and other agencies.

The scope of the inspections appears to be far-ranging. Memorial and several other groups that were inspected said that officials showed the representatives of the groups documents referring to the officials’ authority to check for “compliance with the laws of the Russian Federation” in general.

But a document leaked to the media that provides instructions to local prosecutors’ offices for conducting inspections specifically urges them to analyze sources of foreign funding for the groups and their involvement in political activities, as well as any evidence of “extremism.”

In many cases the officials have provided no advance notice about the inspection. In some cases, the officials have refused to present documents authorizing the inspection but have ordered the representatives of the group to provide immediately all documents the inspectors demand. Several organizations stated on social media that officials thoroughly examined the premises and attempted to probe more intrusively into the groups’ offices, searching libraries for “extremist” literature and requesting to look into computers.

“The inspections are initiated by the prosecutor’s office, which has a wide-ranging jurisdiction,” Dalhuisen said. “This allows the authorities to bypass some of the legal protections groups have under laws regulating NGOs.”

Since Putin’s return to the presidency in May 2012, a parliament dominated by members of the pro-Putin United Russia party has adopted a series of laws that imposed dramatic new restrictions on civil society. A June law introduced limits on public assemblies and raised relevant financial sanctions to the level of criminal fines. Two more laws were passed in July. One re-criminalized libel, while the other imposed new restrictions on internet content. Another law, adopted in November, expands the definition of “treason” in ways that could criminalize involvement in international human rights advocacy.

In December, Putin signed a law allowing the suspension of nongovernmental organizations, and the freezing of their assets, if they engage in “political” activities and receive funding from US citizens or organizations. Organizations can be similarly sanctioned if their leaders or members are Russian citizens who also have US passports.

Russian law envisages unannounced inspections of nongovernmental groups under a variety of circumstances. The “foreign agents” law, for example, authorizes “unannounced” (vneplanovye) inspections upon a request by the prosecutor’s office, among other grounds.

“This ongoing harassment of human rights defenders is contrary to Russia’s international commitments and indicates a fear of free and open discussion about the human rights situation in Russia,” said Andrew Anderson, deputy director of Front Line Defenders.