Mikhail Kosenko faces indefinite detention in a psychiatric institution on charges of mass rioting and an act of violence threatening the life of an official.

UPDATE: On October 8, 2013, Mikhail Kosenko was convicted on charges of mass rioting and an act of violence threatening the life of an official. He was sentenced to forced psychiatric treatment.

Russian authorities should withdraw the charges against a protester on trial in relation to the 2012 mass protest, Human Rights Watch said today. The protester, Mikhail Kosenko, faces indefinite detention in a psychiatric institution on charges of mass rioting and an act of violence threatening the life of an official.

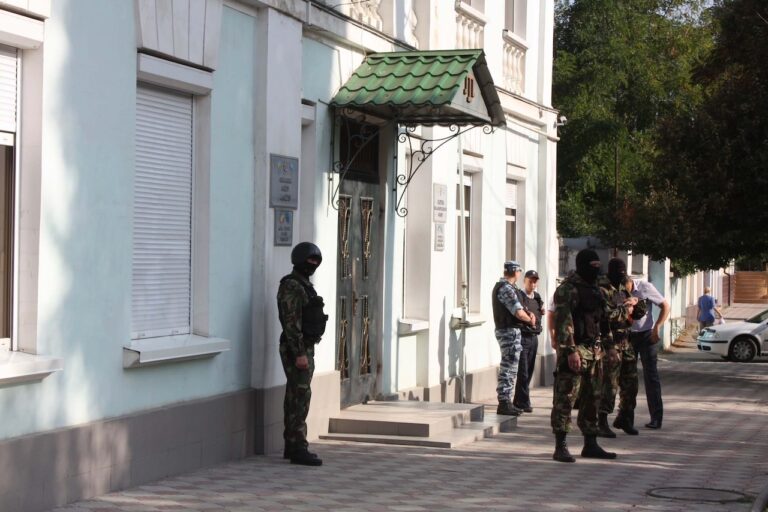

Moscow’s Zamoskvoretski District Court is expected to deliver a verdict in the case against Kosenko on October 8, 2013. A prominent psychiatrist told Human Rights Watch that he considers the case a stark example of the use of psychiatry for political purposes.

“The Russian authorities should end the injustice against Kosenko,” said Tanya Lokshina, Russia program director at Human Rights Watch. “Kosenko should never have been forced to spend 16 months behind bars on grossly disproportionate charges, and now he faces indefinite, forced psychiatric treatment.”

The prosecutor should drop the charges against Kosenko, request his release from custody, and ensure that he is not under any circumstances sent for forced psychiatric treatment, Human Rights Watch said.

Kosenko, who has been in pretrial detention for 16 months, was one of tens of thousands of demonstrators who protested in central Moscow’s Bolotnaya Square on May 6, 2012, the day before President Vladimir Putin’s inauguration. There were scattered clashes between a small number of protesters and police.

Kosenko, who has a mental disability, is one of 25 people charged in relation to the protest. But he was tried separately because the prosecution is seeking his incarceration in a psychiatric institution for forced treatment.

Kosenko is accused of hitting a police officer, Alexander Kozmin, “at least once with his leg and once with his arm” during the protests and tearing off the officer’s protective gear. However, at Kosenko’s trial, which Human Rights Watch attended, Kozmin testified that he could not identify Kosenko as the man who hit him, and stated that he did not want Kosenko to be punished for a crime he did not commit. Another police officer testified that he did not remember Kosenko from the rally and could not recognize him on a video recording of the events.

Three prominent Russian human rights defenders who were standing near Kosenko when Kozmin was attacked also testified that Kosenko did not hit the policeman.

Human Rights Watch scrutinized the video recording the prosecution presented in court and could not find any indication that Kosenko took any part in the violent clash. Amnesty International has named Kosenko a “prisoner of conscience.”

The only witness who supported the prosecutor’s accusation was a policeman who said Kosenko “moved his hands in the direction of” Kozmin. The witness claimed that he recognized Kosenko in the video by the color of his clothes and hair.

“The majority of the evidence, including from the police officer himself, indicates that Kosenko never touched him,” Lokshina said. “The court heard nothing that would justify the charge of threatening the life of the official.”

Kosenko is also charged with participation in “mass riots,” which under Russian law involves “violence, pogroms, arsons, destruction of property, use of firearms and explosives, and putting up armed resistance vis-à-vis an official.” The prosecutor’s office filed the same charge against a number of Bolotnaya protesters, citing beatings of about 40 policemen, damage to police protective gear, destruction of six portable toilets, and an incident in which a Molotov cocktail broke against the road, setting a protester’s pants on fire.

The prosecutor contended that Kosenko acted unwillfully, claiming he was “mentally incompetent,” and asked the judge to commit him to forced confinement in a psychiatric institution.

In 2001 Kosenko was diagnosed with “sluggishly progressing [i.e. mild] schizophrenia.” Since then, his mental health has been regularly monitored by doctors, and he has been on medication. His sister told Human Rights Watch that Kosenko regularly and willingly took his medication, and never showed aggression, needed special assistance, or required hospitalization.

Kosenko had no police record before the Bolotnaya events. His sister and lawyers told Human Rights Watch that throughout his 16 months in custody, Kosenko showed no aggression toward prison staff and inmates, even after learning, through the media, about the death of his mother in September. Authorities did not allow Kosenko to attend her funeral.

In July 2012, forensic psychiatrists from the Serbsky Institute, Russia’s state psychiatric research center, evaluated Kosenko and diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia, a more serious condition that, they claimed, made Kosenko “a danger to himself and others.” They recommend confining him for psychiatric treatment.

In August 2012 Dr. Yuri Savenko, the head of Russia’s Independent Psychiatric Association, a Russian nongovernmental organization, told Kosenko’s lawyers that the Serbsky Institute’s evaluation was deeply flawed. Savenko, a prominent psychiatrist with 50 years of clinical practice, said that the Serbsky Institute experts overlooked 12 years of observations by Kosenko’s doctors, who clearly indicated in Kosenko’s medical history that he was not prone to aggression and had no violent episodes. He said the Serbsky Institute specialists also ignored the fact that Kosenko’s medications were very mild and that he had never required hospitalization.

Kosenko’s lawyers presented this evidence in court and petitioned the court to order the Serbsky Institute to carry out a new evaluation. The court dismissed the petition.

Dr. Savenko told Human Rights Watch that the Serbsky Institute’s assessment of Kosenko was “punitive” and specifically aimed at justifying forced treatment. “The case is emblematic of the use of psychiatry for political purposes,” Savenko said.

The United Nations special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, specifically noted in his report to the UN Human Rights Council in March that “free and informed consent [for psychiatric treatment] should be safeguarded on an equal basis for all individuals without any exception. He also said that the “severity of the mental illness cannot justify detention nor can it be justified by a motivation to protect the safety of the person or of others” and that “deprivation of liberty that is based on the grounds of a disability and that inflicts severe pain or suffering falls under the scope of the Convention against Torture.”

“Kosenko has needlessly spent more than a year behind bars,” Lokshina said. “Committing him to forced psychiatric treatment would be a grave violation of his rights.”