Rwanda's controversial Media Bill is back in Parliament after President Paul Kagame rejected it in an apparent response to petitions by local media and press freedom groups.

(Media Institute/IFEX) – Rwanda’s controversial Media Bill is back in Parliament after President Paul Kagame rejected it in an apparent response to petitions by local media and press freedom groups.

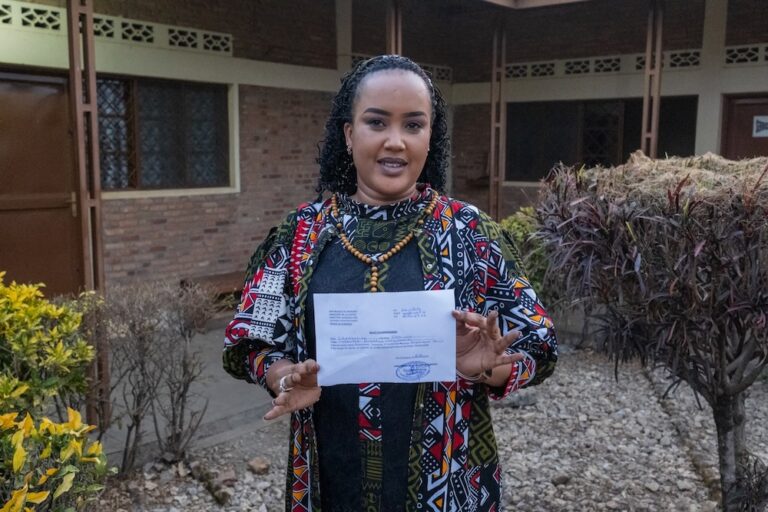

Information Minister Louise Mushikiwabo re-tabled the bill in Parliament on 22 May 2009 together with amendments proposed by the president.

The bill, passed by Parliament in February, was heavily criticised by media watchdogs and local practitioners as infringing on media freedom and civic liberties. The Rwanda Journalists Association (ARJ) petitioned President Kagame to reject the law, arguing that parliamentarians had pushed it through without sufficient consultations. Ironically, both the Senate and Lower chambers are dominated by Kagame’s ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF), and the amendments proposed by the president are likely to be passed without much debate.

Among the clauses the president wants amended, according to Mushikiwabo, are limitations on level of education, qualifications for practicing journalism as well as unlawful access to classified information. He, however, upheld defamation as a crime.

“On who should be a journalist, the president said the article was discriminative and would leave behind many people with potential to practice the profession. He advised that any person should be allowed to practice journalism provided they have relevant training,” Mushikiwabo said, adding that the president felt that this would encourage specialised reporting depending on one’s field of education.

In late March, journalists, media managers and journalism lecturers called for the scrapping of criminal libel from the media bill. A meeting held on 20 March to examine the controversial clauses asked the president to send the bill back to Parliament. Initially, journalists were expected to select a committee to study the legislation but, according to Gasper Safari, the president of ARJ that organised the meeting, a committee could not have represented every journalist’s view.

“We decided to have everyone in the meeting to widen participation as much as possible and forestall complaints about the resolutions. I also think what we have discussed could not have been done by a committee of a few people,” Safari said.

The Rwanda Human Rights Commission seconded a lawyer, Laurent Nkongoli, to interpret the terms and implication of the different clauses for the journalists. Nkongoli said that such a meeting was necessary because of the implications of the legislation upon press freedom and access to information.

“Getting different people’s views through such meetings is very important. Whether they respect the views is another issue. The most important thing is that we have done what we think is right in helping people understand the legislation and its implications,” Nkongoli pointed out.

During their discussion on the bill, journalists recommended that defamation be scrapped off the list of criminal offences, people with qualification in different fields but with added training in journalism be allowed in the profession, and that there be a five-year transition for those practicing journalism without relevant training to access it.

The bill also proposes that journalists be compelled to reveal their sources, failure to which they will be fined Rwf 100,000 to 300,000 (approx. US$180-530).

Another controversial issue is the start-up capital required to open a media house. The earlier draft bill had proposed that any investor seeking to set up a print media house have at least Frw6 million, and radio and television stations between Frw50 million and Frw 100 million, respectively. The president proposed that the requirements be left to a ministerial decree.

The president’s action is not without precedent. Before the existing 2002 press law came into being, he also declined to sign it and proposed a review of articles prescribing a death penalty for those denying that genocide occurred. This and other clauses were subsequently deleted from the law.

Since the passage of the law, numerous international and local groups had protested at the stringent clauses that undermined the independence of the media. In November 2008, before Senate endorsed the bill, the Media Institute and UNESCO conducted a mission to Rwanda that identified the flaws and recommended amendments.

Rwanda has defended itself against criticism of suppressing press freedom by citing unprofessionalism in the media.