David Cecil faces two years in jail on a charge of "disobeying lawful orders" after refusing to let the authorities suspend his play about a gay business man in Uganda.

UPDATE: British theatre producer freed in Uganda (Index on Censorship, 3 January 2013)

(Index on Censorship/IFEX) – 21 November 2012 – “Absolute freedom of speech in enshrined in the constitution. The fundamentals of the law are that you can do and say what you like as long as you don’t incite public disorder and so on. People are unaware of that.”

British theatre producer David Cecil, 34, is talking about Uganda, the country where he has lived and worked in for the past three years.

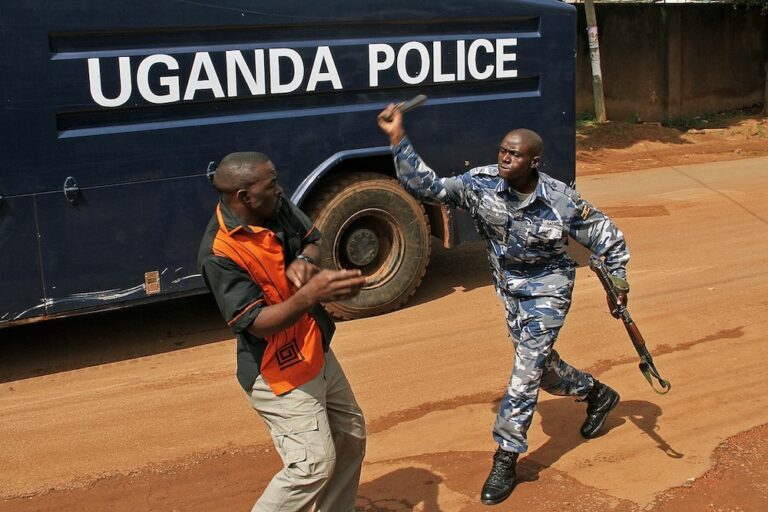

On 13 September, he was arrested in Kampala and held in detention for three days. Eventually released on bail, he now faces two years in jail or deportation on a charge of “disobeying lawful orders” after refusing to let the authorities suspend and review his play the River and the Mountain.

The play, which tells the story of a successful gay businessman who is murdered by his employees when he comes out, was always likely to cause controversy in Uganda.

The country’s terrible gay rights track record received international attention when the Anti-Homosexuality Bill was tabled in 2009. Homosexuality remains illegal in Uganda but the bill sought to introduce the death penalty for “repeat convictions.”

In October 2010 local tabloid the Rolling Stone published the names, photos and addresses of “known homosexuals,” and published a front page headline reading “Hang Them.”

Members of the LGBT community suffered verbal and physical attacks and gay rights activist David Kato — one of the people identified by the paper — was killed in his home in Mukono, outside Kampala, in January last year.

Following widespread international condemnation, the bill was shelved but only to be revived in February 2012, Speaker of Parliament Rebecca Kadaga recently vowing it would pass before the end of the year. The death penalty clause has been removed, but it remains a highly discriminatory piece of legislation and this summer the government attempted to ban 38 NGOs it claimed were promoting gay rights.

Against this backdrop, Cecil was aware the play was likely to be politicised by both sides of the LGBT debate, with outspoken homophobes rallying against it and gay rights groups using it as a launchpad for advocacy. Despite this, he stresses the theatre company’s intention was not to make a political statement.

“It is a drama and it’s quite provocative, but it’s comedy, it’s entertainment. Our intention was to make a comedy drama that would make people think and talk.”

Only days before the play was set to open in August, Cecil received a letter from the country’s Media Council, the body tasked with regulation of media. It stated the play was to be suspended pending an official content review. Cecil and his company, under legal advice, interpreted this as a request rather than an order. Initially, the play was to run at the National Theatre, open to the general public but Cecil decided to move the production to private venues and eight performances were seen by an invited audience. Cecil was arrested after the short run, and branded a gay rights activist by an angry media.

Initially director Angella Emurwon wasn’t worried about a government backlash. In her seven years of putting on plays in Uganda, this was the first time the government asked to review one prior to preview. “For me it was never a question that we would be in trouble, either physically or legally. It was never a thought that entered my mind.”

While Emurwon concedes censorship exists in Uganda, she points to its selective and seemingly random nature. Indeed, in 2005, a local production of the Vagina Monologues was banned and mere weeks after Cecil’s arrest, the play The State of the Nation Ku Ggirikti was suspended. The production is said to criticise corruption and bad governance in President Yoweri Museveni’s administration. But Emurwon says productions critical of authorities have run without any issues.

She has personally not experienced any backlash, but is worried about Cecil and finds the whole situation scary.

“I’ve noticed that people pay a lot more attention to what I say. Every word I utter has gravity. That means I have to be very careful about what I say. That is not the sort of person that I am, so that has been difficult. I feel like I’m becoming a self-censor, because everyone can take something that I’ve said and make it into a big deal.”

Cecil’s second hearing is taking place tomorrow. There, it will be decided if the prosecution have enough evidence to take the case to court. Cecil’s legal team will argue that there were no references to any parts of the constitution or penal code in the letter from the Media Council. It did not refer to any legal consequences if they should choose to perform the play. Furthermore, Cecil says the Media Council is supposed to be an advisory body, it holds no executive authority over individuals’ rights to express themselves.

A petition calling for the charges against Cecil to be dropped has been signed by more than 2,500 people, including Mike Leigh, Stephen Fry, Sandi Toksvig and Simon Callow. The petition was organised by Index on Censorship and David Lan, the artistic director of the Young Vic.

While Cecil warns artists in Uganda against trying to directly influence policy through their art — labelling it a “risky and even ill-advised” strategy — but he hopes some positive changes will come from his case.

He wants other artists to see that:

“not only is it possible to put on a play about something quite controversial, but [they] will see the importance of if, and see that by making controversial statements, you are actually reaching a lot more people.”