(RSF/IFEX) – The following is an RSF report: RWANDA Discrete and targeted pressure The President Paul Kagame is a predator of press freedom A delegation of Reporters Sans Frontières (Reporters Without Borders – RSF) went to Rwanda from 2 to 10 October 2001 in order to assess the press freedom situation. Please find below this […]

(RSF/IFEX) – The following is an RSF report:

RWANDA

Discrete and targeted pressure

The President Paul Kagame is a predator of press freedom

A delegation of Reporters Sans Frontières (Reporters Without Borders – RSF) went to Rwanda from 2 to 10 October 2001 in order to assess the press freedom situation. Please find below this RSF report.

Introduction

Between April 6th, 1994, the start of the Rwandan genocide, and the rise to power of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (FPR) in July the same year, at least 48 press professionals were killed in the country. Most of them were killed in the early days of the genocide, as if the regime were trying to silence the opposition’s voice and all those who condemned the massacres that were underway. It is impossible to know for certain whether they were eliminated because of their ethnic affiliation, their political opinions, their journalistic activities or for all three reasons.

Other “journalists” preached hatred. The executives and presenters of Radio-télévision libre des mille collines (RTLM) and the newspaper Kangura, to mention only the best known of these “hate media”, called for murder and encouraged the people to help in the killings.

By the time the genocide was over there was practically nothing left of the Rwandan press. Several months elapsed before certain titles reappeared or new ones were created. Today things have calmed down. Surviving journalists or those returning to the country from exile are working together on newspapers and magazines in Kinyarwanda, English and French. The “hate media” have vanished, leaving behind a press corps generally close to the authorities and marked by strong self-censorship.

A Reporters Sans Frontières (Reporters Without Borders – RSF) delegation visited Rwanda between October 2nd and 10th, 2001, to examine the country’s press freedom situation, and in particular the new press law, passed on September 28th, 2001 by parliament. RSF’s representatives received permission from the Ministry of Home Security to visit the prisons of Kigali, Gitarama and Butare in order to interview imprisoned journalists. The organisation was also granted interviews with the parliamentary president and the public prosecutor. RSF’s last visit to Rwanda was in 1996. Twice, in 1999 and 2000, the authorities rejected its request for visas.

Jailed journalists

There are at least ten journalists in Rwandan jails, all accused of participating in one way or another in the 1994 genocide. RSF was able to meet with seven journalists in various prisons in the country. RSF feels that only two of the arrests are linked with press freedom and the prisoners’ professional activities. These are Dominique Makeli and Tatiana Mukakibibi.

In four other cases (Ladislas Parmehutu, Telesphore Nyilimanzi, Gédéon Mushimiyimana and Joseph Habyarimana), RSF has insufficient information to determine whether or not they were involved in the genocide. It appears that the reasons behind the arrests of Joseph Ruyenzi and Domina Sayiba have more to do with quarrels and rivalries between their families and those of the plaintiffs. Their detention is therefore not linked to their professional activities. In all the other cases, it is very likely that the journalists called for ethnic hatred before and during the genocide. RSF even lodged a complaint against some of them in 1994 for “defending war crimes and crimes against humanity”.

In 1996, 1999 and 2001, the authorities drew up a list of “first category criminals”, naming those persons suspected of having been the “planners, organisers, inciters, supervisors and overviewers of the crime of genocide”, as well as those who may have committed “acts of sexual torture”. The list contains about 2,900 names, including 29 journalists. They all risk the death penalty. Some are held in Rwanda or in Arusha (the International penal tribunal for Rwanda); others are still at large; a few have died.

Radio Rwanda journalist Dominique Makeli is being held in the Kigali central prison (PCK). In the early days of the genocide, Dominique Makeli fled to Kibuye in the west of the country, where one of his sons had been killed a month earlier by the Interahamwe (extremist Hutu militia). On September 18th, 1994, back in Kigali, he was arrested at his home by an agent of the military department of information (DMI). The next day he was taken to the Remera police station. Two weeks later, he was transferred to Rilima prison, where he spent six months in solitary confinement. His wife first received news from him in November.

In 1995 and 1996, he was accused of organising demonstrations in the prison. He was beaten on several occasions, as was another journalist, Amiel Nkuliza. In March 1997, more than two years after he was first arrested, the courts questioned him for the first time. A judge asked him a few questions but did not tell him what he was accused of. In March 1999, the substitute public prosecutor accused him of having refused to shelter a Tutsi during the genocide. At the end of the year, the council chamber (the accusation chamber) accused him of having “taken part in the attacks.” Dominique Makeli denies this, and the substitute general prosecutor ordered that he be kept in preventive detention for two more years.

The general prosecutor, Sylvaire Gatambiye, told RSF that Dominique Makeli is accused of having “incited genocide in his reports.” In May 1994, he covered an apparition of the Virgin Mary in Kibeho (west of Butare) and made the following statement in his supposed incitement: “The parent is in heaven.” The prosecutor explained that in the context of the time, this signified that “President Habyarimana is in heaven.” People are said to have interpreted this message as God’s support for the former president and, by extension, for the policy of extermination of Tutsis.

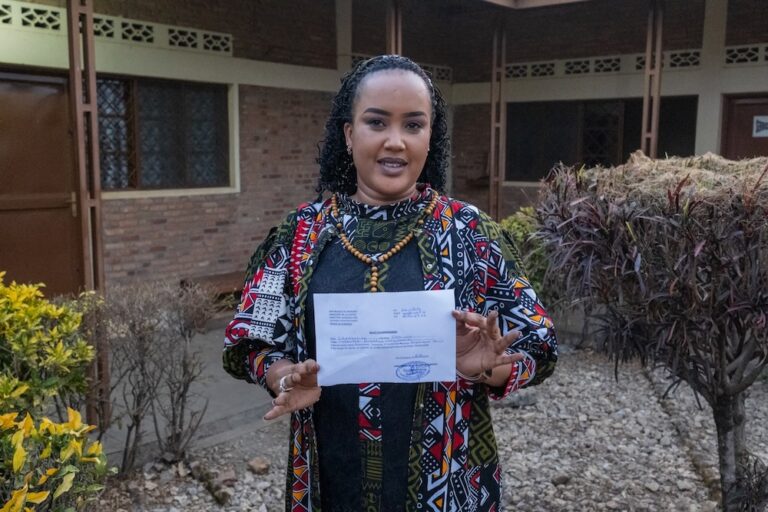

Tatiana Mukakibibi was a presenter and programme producer at Radio Rwanda. Beginning on April 6th, 1994, she read on the air the official press releases and lists of people killed, which were sent in by the various prefectures of the country. On July 4th, the radio station broadcast a final press release announcing that Kigali was being evacuated. Tatiana Mukakibibi sought refuge in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) with other journalists. On August 10th, she returned to Kapgayi (near Gitarama), Rwanda, where she worked with Father André Sibomana (former director of Kinyamateka and a winner of the Reporters Sans Frontières – Fondation de France prize, who died in 1988). She was arrested and held for several days in July 1995. Fearing reprisals, she fled to Uganda but returned again to Rwanda on September 30th, 1996. Two days later, the police arrested her at her home in Ntenyo (Gitarama). Tatiana Mukakibibi was thrown into a common cell, where she is still being held in very harsh conditions.

The day after her arrest, a police inspector named Emmanuel Ruganza asked her to state that she had gone to Uganda under the protection of Father Sibomana. If she confessed, he assured her, she could go free at once. She refused. Five days later she was accused of having handed out weapons and killed Eugène Bwanamudogo, a Tutsi who made radio programmes for the Ministry of Agriculture. The substitute public prosecutor of Gitarama confirmed these accusations in the

summer of 2001. According to Tatiana Mukakibibi, she is being framed by the people in her village because André Sibomana send reports to international organisations to tell of the exactions committed by Tutsis in reprisal for the massacres of April 1994. According to the journalist, certain persons mentioned in these documents may have tried, through her, to arrest André Sibomana.

Nationwide television was no longer operating normally from April 6th, 1994. Ladislas Parmehutu did two final reports before fleeing to the DRC on April 25th. One of the reports was about the end of the school year in the north of the country, still relatively spared the killings, and the other report dealt with the bombing of Kigali hospital by the FPR forces. He returned to Rwanda in 1996 and was immediately arrested by the city police of Byumba, in the north of the country. After spending three years in the prefecture’s prison, he was transferred at the end of 1999 to the PCK. He has been questioned on six occasions, but no one has ever told him what he is accused of.

According to Joseph Habyarimana, he is in prison for articles published in issues 24 and 25 of the newspaper Indorerwamo. He wrote there that a woman named Immaculée Mukamurenzi, from the Cyahafi sector of Kigali, who is very influential in the local administration, wanted to imprison the Hutus in her neighbourhood, whom she accused of having participated in the genocide. “This woman told my sister one month before my arrest that she ‘would get me’!” he says. He was arrested on October 28th, 1997, and taken to a cell in the area. One week later, he was transferred to the PCK. That same day, Joseph Habyarimana was questioned and accused of having participated in a collective attack on Mount Jari (Kigali) and of having returned to the city and played soccer with a human head. He denies the accusations against him. Lacking proof, RSF is incapable of giving an exact motive for Joseph Habyarimana’s detention.

In 1994, Gédéon Mushimiyimana was a teacher in Butare, in the south of the country. During the genocide, he took shelter in Gikongoro, to the west of Butare. His wife and daughter were killed in April that year. In 1995, he became a journalist for the national television network. A year later, he was arrested in Kigali by the police and accused of having “given information” to Radio France Internationale (RFI) claiming that Paul Kagamé, the country’s vice-president at the time, was a “terrorist”. Gédéon Mushimiyimana had indeed been in contact with an RFI journalist who had come to the country a few weeks previously to do reports. The journalist had gone to the television offices, and he had given her tapes of reports done by the public network. A few days after his arrest he was finally accused of having decimated a family during the genocide. A police officer told him that witnesses would be coming to identify him. He was kept in a cell at the police station for six months but was never confronted with witnesses. In May 1999, he was transferred to the Kigali central prison, where he was questioned by the council chamber. He was then accused of having been an accomplice in his wife’s death. Gédéon Mushimiyimana is now being held in the Butare prison.

Telesphore Nyilimanzi was a department head at Radio Rwanda until July 4th, 1994. He then left Rwanda for the DRC. In December 1996, he returned to Rwanda and held various jobs at the Ministry of Information, then at the Ministry of Local Administration and Social Affairs (MINALOC, in charge of information). On July 5th, 2000, the day he was arrested, he was working for the provisional election commission. In August, he was accused by the council chamber of having been a “planner and inciter in his job as department head at the radio” of the massacres of the Bagogwe people in the north of the country, and the Batutsis in Bugesera in 1992. Six months after his arrest, his name appeared on the “first category of criminals” list. He says that his name is on the list because a BBC journalist, one Séraphin Byiringiro, managed to get his name on the list. In June 1994, Byiringiro wanted to resume his job at the radio station after having been sheltered in the Hotel des Mille Collines, but the editorial board, headed by Telesphore Nyilimanzi, refused. The former head of the national radio station told RSF that “Radio Rwanda did not broadcast any abominations” in April 1994.

Joël Hakizimana, editor-in-chief of Kangura, and Valérie Bémériki of RTLM, are also being held at the PCK. These two journalists, who are on the “first category of criminals” list, are among the main figures in the “hate media”.

Several jailed journalists will be tried before the gacaca (people’s courts, without any possibility of appeal, constituted by the Rwandan authorities to speed up the trial process). RSF hopes that these trials, which will be conducted by citizens, will not be an occasion to settle old scores and that they will sit in impartial judgement of the facts levelled against the jailed journalists.

Other media professionals jailed in the wake of the genocide have recently been freed on bail. Albert-Baudouin Twizeyimana, a former journalist at Radio Rwanda and now a reporter for Kinyamateka, spent more than three years in prison. He was arrested on May 11th, 1996, while reporting the news on the radio. At first, he was accused by the police because of what he said on the air, although he was only reading an official press release from the authorities. A little later, he was accused of having taken part in the genocide and in particular of having played a role in his wife’s death. The journalist says that she died of a disease at the end of 1994 and that he wasn’t even with her at the time. According to him, it is a Tutsi woman who has “invented all this.” Albert-Baudouin Twizeyimana was granted bail on December 30th, 1999. He had spent more than two years in Nsinda prison in very difficult conditions. With only one water tap for several thousand prisoners, inmates had to try to capture rainwater or buy water from those who were let out temporarily to work in town.

Amiel Nkuliza, editor of the Partisan, spent more than two years in prison between May 1997 and August 1999. He was accused of “undermining state security” for having published photos of inmates who were smothered to death in the Kigali central jail. The police seized all copies of the issue containing the pictures at the printer’s. He is now out on bail but must remain “at the disposal of the justice department” and is barred from leaving Rwanda.

The lack of plurality

No daily newspapers are published in Rwanda. The governmental press notwithstanding (Imvaho, La Relève), there are fewer than a dozen private weeklies and monthlies. Half of these titles are written in Kinyarwanda, and the other half in English and French. Excluding the weekly Umuseso, which everyone agrees is relatively independent, all the others are more or less close to the authorities. At least four of the titles (Grands lacs hebdo, The New Times, L’Enjeu and L’Horizon) can be called pro-government. They survive through the various state administrations buying advertising space (Rwanda Revenue Authority, the Secretariat of Privatisations, the Election Commission, the Constitutional Commission, and so forth) and the big public-owned companies (Rwandatel, SONAOA, and so on). A human rights activist says that it is “an intelligent way for the state to buy the papers.” He adds that these publications have “nothing to say but are there only to thwart the independent press and not leave it any room.”

Print-runs are no larger than 4,000 copies, and the near totality of the readership is in the Kigali region. Numerous titles appear at very irregular intervals and on a one-off basis whenever the cashflow permits. The papers are expensive (between 100 and 500 Rwandan francs, i.e. .25 to 1.25 euros) and are unaffordable to the majority of Rwandans.

The audiovisual sector is at the exclusive service of the present power structure. An executive in a human rights organisation stresses that one can talk about “governmental media”, but not “public media.” Radio Rwanda and Télévision nationale du Rwanda (TVR) are the only press organs available on a national scale. Radio is by far the most accessible medium for the Rwandan people. Privately owned radio and television, set out in the 1991 law on the press, are in fact forbidden. The authorities have on several occasions invoked the tragic consequences of the creation of RTLM to reject broadcasting authorisations to private entrepreneurs.

In these circumstances, it is not possible to speak about a real plurality of information in Rwanda. Certain topics such as the presence of Rwanda in the Democratic Republic of Congo or the FPR’s reprisals are taboo. Numerous journalists admit that they censor themselves for fear of reprisals. One director says, “The pressure hasn’t decreased; it is the journalists themselves who have disarmed.”

The press house in Kigali, inaugurated in January 2000, enables journalists to make photocopies, send faxes and lay out their publications at special rates. All the printed press titles that appear in Rwanda are printed in Uganda. According to several directors, the costs are cheaper and the quality is much better.

The Rwandan Journalists Association (ARJ) is working in slow motion and seems to have lost all credit among journalists. Its president, James Vuningoma, interviewed by the RSF delegation, didn’t even know the names of the journalists held since 1994. The ARJ is doing nothing for them and has not visited them in prison. The steps it has undertaken relating to the new law on the press are not clear and are, in any case, not very effective.

Several foreign and national observers agree that the Rwandan press is of mediocre quality. Numerous Rwandan journalists have no training and do not check their information sufficiently. A School of Information Science and Technology (ESTI) has existed for three years, but according to certain former students, its courses remain too theoretical and not professional enough.

Incessant pressure and threats

In February 1999, John Mugabi, editor-in-chief of the English-language newspaper Rwanda Newsline, was summoned by the Prosecutor General. He was arrested at once, pursuant to a complaint for defamation by Frank Rusagara, secretary general at the Ministry of Defence. In the newspaper’s 24th issue, Rsagara was accused of accepting bribes while procuring spare parts for Rwanda’s combat helicopters. According to the prosecutor, the journalist was arrested because he refused to divulge the name of the “highly-placed official at the Ministry of Defence” who had blown the whistle. On May 21st, he was freed on bail. A year later, John Mugabi and Shyaka Kanuma, a journalist at the same paper, were summoned by the Prosecutor General and held for two days. Rwanda Newsline had published an article criticising Paul Kagamé, then vice-president of the republic.

On June 1st, 2001, the former head of state, Pasteur Bizimungu, officially launched the Democratic Party for Renewal (PDR). He contacted the press, and in particular Thomas Kamilindi, a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) correspondent, and Lucie Umukundwa, a Voice of America (VOA) correspondent, to grant them interviews about his party. The journalists did their job but almost immediately received threatening calls from the leaders of the secret services. Under pressure, the two journalists finally handed over their tapes to the authorities. That same day, Ismaël Mbonigaba, director of Umuseso, and Shyaka Kanuma were arrested after interviewing Pasteur Bizimungu. They were finally released at midnight. Shortly after the incident, John Mugabi of the Rwanda Newsline was accused of being a member of the PDR, and fearing reprisals, left the country for refuge in Europe. With the departure of its director, the Rwanda Newsline ceased to appear. Pasteur Bizimungu has now officially been forbidden from contacting the press.

Ismaël Mbonigaba stated that his newspaper, which was part of the same press group as Rwanda Newsline, was “under an advertising embargo.” He receives no advertising from the state or from semi-public companies. International organisations alone continue to buy space in the weekly. In 2001, Umuseso translated excerpts of an interview given by the head of state to a Ugandan newspaper into Kinyarwanda. In the interview, the head of state qualified the king’s party in exile, UNAR, as “extremist.” At once, the FPR declared on national radio that the Umuseso’s politics were known and that the newspaper wanted to “tarnish the image of the FPR.” According to Ismaël Mbonigaba, the entire editorial staff now feels threatened, as the newspaper has become an enemy of the FPR and the president and is therefore vulnerable to strong reprisals. The newspaper published original excerpts of the Ugandan newspapers in English to prove that the head of state had indeed said what it had reported. Three times in the past, Umuseso was forced to publish denials by the FPR. Imvaho and The New Times have published articles against the independent weekly.

The death penalty for journalists

A new law on the press was adopted by parliament on September 28th, 2001. The text is to be studied by the Supreme Court before being applied by the head of state. Local journalists have paid particular attention to three articles (88, 89 and 90) of this law. Article 88 of the draft law (the final text voted on by parliament was not available at the time of this report’s publication) states that “whoever tries to incite part of the Rwandan population by means of the press to commit genocide, even if it is not followed, is punishable with imprisonment for from 20 years to life”. Article 89 states, “whoever tries to incite part of the Rwandan population to commit genocide by means of the press … risks the death penalty”. Numerous journalists contest the fact that such a measure should be written in the press law and not in the penal code or the law on genocide. But the main fear is the abusive use that might be made of these articles. RSF considers in particular that this leaves the door wide open to arbitrary sentencing of critical journalists or members of the opposition. According to a local journalist, this law could have made it possible to sentence Pasteur Bizimungu to death for the statements he made in an interview given to the weekly Jeune Afrique – L’Intelligent. The former head of state in particular stated that given the present situation, new massacres could be perpetrated in the country.

While on its visit, RSF shared its concerns with the parliamentary president. He wanted to be reassuring and explained that “the abuse that could be made of this law would be extremely dangerous.” Yet he asked not to “focus on this part, which is not there to prevent free speech but only to impose limits.” For Noël Twagiramungu, one of the leaders of the League of Personal Rights in the Great Lakes region (LDGL), a danger exists: “someone would give his or her political stance, and they would say that might lead to genocide. This law is much more repressive than the previous one in 1991.”

Moreover, this new law sets out prison sentences for certain press infractions. The “invasion of privacy” is thus punishable by a sentence of one month to one year in prison. RSF points out that in a document published in January 2000, the United Nations’ special rapporteur for the promotion and protection of freedom of opinion and expression stated that imprisonment as a sanction for the peaceful expression of an opinion constitutes a “serious human rights violation.”

The text is also questionable from the point of view of penal responsibility. Article 96 sets out that those responsible for infractions committed through the press are, in order, directors of publications, the authors of articles or reports, printers, vendors and poster hangers. Newspaper vendors, for example, who have no responsibility in a publication’s written policy, could be sentenced to prison terms if the journalists or the heads of the said publication cannot be located or are in flight abroad. This provision would be a strong incitement for printers and vendors, indispensable elements in the distribution chain of information, not to accept publication or sell only papers favourable to those in power.

Missing persons and murder: a regime of impunity

On August 19th, 1995, Manasse Mugabo, director of the Kinyarwanda section of Radio Minuar, the United Nations station in Rwanda, left his home on a trip to Uganda. He never arrived, and since then, no one has had any news of him. The security services state they opened an inquiry, but no one knows the findings. On October 4th, concerned by the authorities’ bad faith, the United Nations mission made Manasse Mugabo’s disappearance public. A source close to the journalist pointed out that he had received direct threats from officers in the Rwandan Patriotic Army (APR). Questioned by RSF in April 1996, the director of the Rwandan Office of Information (Orinfor), Wilson Rutayisire, and the country’s president, Pasteur Bizimungu, rejected any responsibility by Rwandan authorities in the affair.

On April 27th, 1997, Appolos Hakizimana, editor-in-chief of the privately owned bi-monthly Umuravumba, was shot twice in the head. Three weeks earlier, the journalist barely escaped being kidnapped from his home. On July 30th, 1996, he was arrested and accused of being an Interahamwe but was released a few weeks later.

On May 5th, 1998, while returning home from his job as head of the production department of national television, Emmanuel Munyemanzi disappeared. Two months earlier, the journalist was accused of sabotage by Orinfor’s director, following a technical incident during the recording of a political debate. Suspended from his functions, he was transferred to Orinfor’s bureau of Studies and Programmes. At about the same time, Mr. Rushingabigwi, director of national television, was fired for having defended Emmanuel Munyemanzi. In June 1998, the authorities announced that his body had been found near the Kiyovu Hotel in Kigali, but no one had been able to formally identify him.

According to information gathered by RSF in Rwanda, no serious inquiry was carried out in these three affairs, thus creating a genuine climate of impunity in the country. Several journalists state that if one of them were murdered today, the inquiry would be very quickly buried, and no one would worry.

Conclusions and recommendations

Press freedom is not guaranteed in Rwanda. Journalists continue to suffer threats and pressure. All press professionals that RSF met with, including international correspondents, confess that they censor their own writing and that certain topics cannot be treated without drawing the ire of the authorities, in particular the presidential services. This strong self-censorship does nothing to promote the development of a genuinely independent press and harms plurality of information. Rwandan newspapers are monotonous, and beyond a few critical articles or editorials, the information circulated is largely favourable to the powers that be.

It is impossible to ascertain with certainty the motives for the detention of most of the imprisoned journalists. On the other hand, it is legitimate to worry about the slowness of the procedures and the general vagueness that reins in the accusations. Even if one should not forget the local context and the fact that the country lived through an unprecedently violent war, it is unacceptable for a journalist to remain in jail, for example, for seven years without being tried.

The Rwandan situation is unique. It is the one country in the world where the “hate media” has done the most harm. Their impact on the people was a determining factor in the genocide. On the other hand, that should not be used as an excuse to reduce opposition voices to silence. For several years, the government invoked the case of RTLM to prevent the creation of new private radio stations. But it should be remembered that RTLM emerged from the desire of the regime at the time. This argument no longer holds up today. The authorities have no reason to prevent private audiovisual media from developing except for their determination to keep tight control on electronic information.

The head of state, Paul Kagamé, is a press freedom predator. His undeniable role in everything that touches the media and his direct influence in the arrests of journalists make him a central character in the pressure that weighs on the Rwandan media. Numerous journalists confess that they censor themselves for fear of direct reprisals from the head of state or his services. Little given to criticism, the president understands that discrete and targeted pressure is sometimes more effective than hardline, police repression.

RSF asks the Rwandan authorities to:

– free, as soon as possible, Dominique Makeli and Tatiana Mukakibibi,

– grant bail to Ladislas Parmehutu, Telesphore Nyilimanzi, Gédéon Mushimiyimana and Joseph Habyarimana until their trials and while waiting for the formulation of detailed charges,

– speed up the procedures concerning all press cases,

– see that all other jailed journalists receive fair and equitable trials,

– open or re-open investigations concerning all cases of missing persons or the murders of ournalists since 1995,

– see that journalist are no longer victimised by pressure and threats.

RSF asks the Rwandan Supreme Court to:

– suppress articles 88, 89 and 90 from the new press law, as well as all prison sentences set out for press infractions,

– modify the regime of penal responsibility in case of press infractions.

RSF asks international donors, especially the European Union to:

– condition economic aid to Rwanda on the development of a genuinely independent and pluralistic press in the country, particularly the installation of private radio and television networks,

– monitor the work of the gacaca so that these courts do not render justice arbitrarily and unequivocally.

Investigation: Jean-François Julliard

November 2001

This document has been produced with financial aid from the European Union. The points of view expressed herein are those of Reporters sans frontières. In no way do they express the official point of view of the European Union.