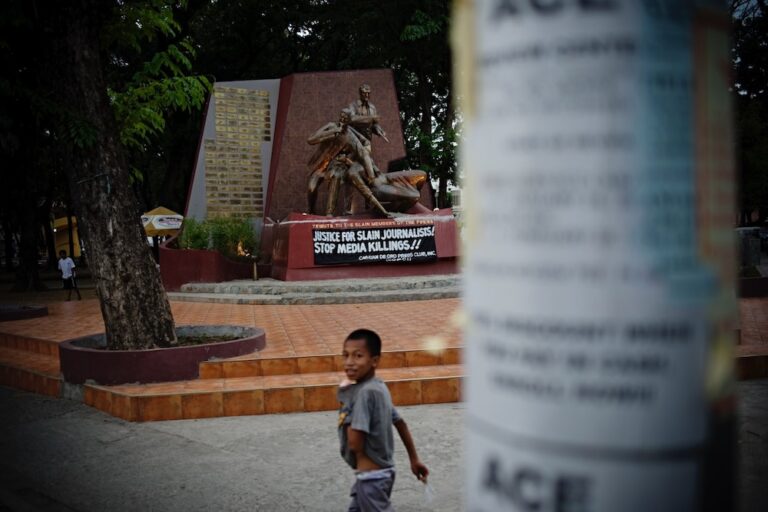

The killing of journalists in the Philippines is continuing, with 134 killed in the line of duty out of a total number of 201 killed since 1986. Two of the most recent killings depart from the usual pattern, in that Manila-based journalists were targeted.

Analysis by Luis V. Teodoro, former dean of the University of the Philippines College of Mass Communication, where he teaches journalism. He is the deputy director of the CMFR and writes a weekly column for the BusinessWorld.

The numbers alone should be cause for concern. The killing of journalists is continuing, with 134 killed in the line of duty out of a total number of 201 killed since 1986. Sixteen have been killed since 2010, when Benigno Aquino III assumed the Presidency – on a promise, one might add, to end the killing of journalists and media workers, and the extrajudicial killings of human rights defenders, environmentalists, pastors and priests, left-wing activists, lawyers and judges, and reform-minded local officials.

As disturbing as the numbers are, two of the most recent killings also depart from the usual pattern.

Most of the journalists killed since 1986 were from the communities, with only one from the National Capital Region (NCR), Daniel Hernandez of the People’s Journal, killed in 1997, and another, Marlina Sumera of radio station DZME nine years later, in 2011. These were thought to be mere exceptions to the pattern, established in 1986, in which NCR-based practitioners enjoyed such a level of immunity from the killings most of them once ignored what was happening to their provincial counterparts.

The fact that Richard Kho and Bonifacio Loreto Jr., who were killed on July 30 this year were based in Metro Manila and were columnist and columnist-publisher, respectively of the defunct tabloid Aksyon Ngayon, is an indication that the relative immunity of NCR-based practitioners from the killings that have mostly plagued their province-based counterparts is giving way to the sense among those who resent the reporting and/or commentary of journalists that they could also get away with the murder of practitioners in NCR.

The killing of journalists in the communities has been blamed on the weakness of the justice system at the local level among other factors. This weakness has been long manifest in the involvement of police and military personnel in the killings (some 70 members of police, militia and security forces, for example, are among the suspects in the Ampatuan Massacre of 2009), the shortfall in the number of provincial prosecutors, and the complicity of local officials.

Since 2003 it has been widely assumed that this was not the case in NCR, where journalists supposedly enjoy the protection of the police and the justice system as well as of the local and national governments. It now seems, however, that both the force of the examples of those killers of journalists as well as masterminds in the killings in the communities has not been lost on the killers of Kho and Loreto, and that the protection NCR-based journalists think they have could be an illusion.

Both killings in fact occurred in the same week that broadcast journalist Ces Drilon of the ABS-CBN network was receiving threatening text messages in connection with a report she did on one of the Ampatuan clan’s lawyer’s alleged purchase of Ampatuan properties. The inevitable conclusion is that the Kho and Loreto killings and the threats against Drilon could indicate the further emboldening of those who would silence journalists in the context of the continuing failure of the justice system and the entire government to bring most of the killers of journalists to justice.

Some of the killers of journalists have indeed been prosecuted, convicted and sentenced. But not only are these positive instances a mere handful – 10 individuals in the same number of cases convicted out of the hundreds of cases, suspects and accused in the killings (197 individuals are accused of masterminding and carrying out the Ampatuan Massacre alone) – no mastermind has ever been convicted either. In what has become a leading symbol of justice system ineffectuality, the implications of State failure to take the accused masterminds in the killing of Tacurong city journalist Marlene Esperat into custody despite the reissuance of a warrant of arrest is not likely to be lost on other would-be killers of journalists.

Beyond these, however, is the reality of what is happening in the Ampatuan Massacre and other trials. Interminable delays due to technicalities are demonstrating that punishing the masterminds and killers in the murders of journalists could be as forlorn a hope as the passage of a Freedom of Information bill even as they encourage the killing of journalists by those affected by news reports and/or media commentaries.

The result is not only the encouragement of those who would silence journalists by killing them, but also these individuals’ casting a wider net to include even the most prominent practitioners. It’s a chilling indication that the justice system is failing not only in the communities, but in the country’s capital as well. For this the media and the citizenry can blame only State ineffectuality, outright incompetence, and sheer lack of interest and concern in putting a stop to the killing of journalists.