The Philippines' libel law has made the media's monitoring role and assisting the public through accurate information in the task of exacting official accountability, more difficult than it already is.

IFEX members have expressed concern about a spate of assaults on press freedom by political and business figures in the Philippines in recent weeks. The upsurge in libel complaints and other legal roadblocks thrown in the way of journalists may well have an effect beyond the individuals immediately affected, including increased self-censorship by the media.

The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), an affiliate of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), has reported a series of incidents including the conviction of a columnist in a libel case filed by a politician, libel suits against journalists uncovering a businesswoman’s alleged involvement in a multi-billion peso corruption scandal and journalists being barred by police from covering the elections of a regional political group.

Libel in the Philippines is a crime punishable with a fine, imprisonment for up to six years, or both. Two journalists were convicted for libel in the past few days, the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) reports. Both were ordered to pay fines totaling PHP2,212,000 (some US$50,000).

On 29 August 2013, a court in Cebu City found columnist, TV broadcaster and radio station manager Leo Lastimosa guilty of a libel complaint filed in 2007 by Cebu’s third district representative Gwendolyn Garcia.

Lastimosa says comments in his 2007 article in question did not relate to Garcia, who was then governor, but the court did not agree. “I’m interested to know how many have been convicted for satire,” Lastimosa told CMFR. He plans to appeal.

In a separate case, Sun.Star Davao editor-in-chief Stella Estremera and former publisher Antonio Ajero were also convicted of libel on 3 September in Digos City, in connection with a 2003 article.

The article had cited a police document identifying illegal drug pushers and users who had surrendered to the authorities. Complainant Baguio Saripada was on this list. The reporter who wrote the story had unsuccessfully tried to contact Saripada for comment. Nevertheless the court decided to convict Estremera and Ajero, saying that the journalists failed to get Saripada’s side of the story.

“It was a simple police report that every [journalist] does,” Estremera told CMFR. “It just goes to show that if somebody is really determined to silence you, there is a legal instrument (to do) it.”

Renewed calls for the decriminalisation of libel

In a much publicised case, in August, lawyers for businesswoman Janet Lim-Napoles filed four libel complaints against five journalists, from the Philippine Daily Inquirer and Rappler.com, a newspaper publisher, a blogger, a legal consultant and a fashion designer.

Napoles has been in hiding since figuring in an alleged corruption scandal. In July, the Philippine Daily Inquirer released a series of reports on a “pork barrel scam” in which fake non-government organizations (NGOs) allegedly misused at least P10 billion (some US$200 million) of public funds sourced from senators, congressmen and local officials. Whistleblowers identified Napoles as the head of several of these fake NGOs and as a major beneficiary. Rappler.com also reported on the alleged lavish lifestyle of Napoles’ daughter Jeane and on a property in her name in Los Angeles.

CMFR and the IFJ are advocating for the decriminalisation of libel, stressing that the law has been used primarily to suppress free expression rather than to address media abuse.

A libel law can be a legitimate means of redress for people the media have aggrieved, and can even encourage greater media responsibility, CMFR noted. But the antecedents of the present libel law, in both the Spanish and US colonial periods, was primarily used to prevent criticism of both colonial regimes and to curb Filipino demands for independence, and the current libel law has been used to intimidate and silence journalists.

If it takes place, the decriminalization of libel presents the media with a challenge as well as an opportunity, CMFR cautions, as it will require them to raise their capacity for self-regulation.

Nevertheless, according to CMFR, the present libel law has made the media’s monitoring role and assisting the public through accurate information in the task of exacting official accountability, more difficult than it already is.

“There is a constant pattern in the Philippines where the wealthy and the powerful seek to misuse both the law and the authorities in attempts to prevent legitimate scrutiny of their activities . . . [and] to silence or punish the media for carrying out legitimate investigations into corruption and misbehaviour,” the IFJ stated.

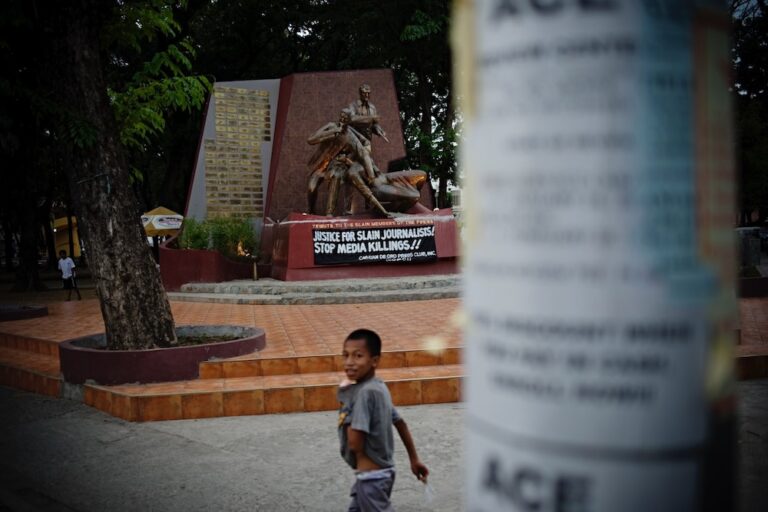

“The culture of impunity in the Philippines, that fails to protect the media, that fails to bring to justice the guilty, allows the unscrupulous to escape scrutiny and undermines democracy. The IFJ calls on the administration of President Aquino to remove libel from the criminal statutes; fully investigate the allegations of corruption; ensure the entire political process is open, transparent and subject to legitimate scrutiny; and bring to justice those responsible for the harassment and murder of our journalist colleagues.”