The history of House resistance to a Freedom of Information act in the Philippines drives current concerns on whether the bill will pass that chamber, where a number of versions have been filed by several representatives.

UPDATE from CMFR: Senate committee approves FOI bill (20 September 2013)

The Freedom of Information bill filed by the Right to Know. Right Now! (R2KRN) Coalition is likely to pass the Senate, if experience during the 14th and 15th Congress is any gauge. The version filed by then Congressman Lorenzo “Erin” Tañada III passed the Senate in both Congresses with hardly any amendments. But it failed to pass the House of Representatives in 2010 and early 2013.

A supposed lack of quorum on its last session day killed the bill in the 14th Congress, which ended in 2010, while the failure of the House Committee on Public Information to submit the bill to the plenary for discussion put an end to it in the last days of the 15th early in 2013.

The history of House resistance to an FOI act drives current concerns on whether the bill will pass that chamber, where a number of versions have been filed by several representatives – or whether, as in the aftermath of the 14th and 15th Congresses, the bill will have to be resubmitted to the next Congress in 2016.

As valid as these concerns are, however, what’s even more fundamental is what the final version of the bill will look like should the bill pass both Houses and it is signed into law. The bill filed by R2KRN through citizens’ initiative already contains provisions that could make it difficult or even impossible to obtain information crucial to the exercise of free expression and press freedom, and even the safety of journalists and politically active citizens. These provisions constitute the compromises the coalition thought were necessary to “accommodate” Malacañang and Philippine security forces concerns so as to enhance the bill’s chances of approval.

In addition to the accommodation with Malacañang’s preference for the retention of the provision exempting from public access information on inputs to executive level discussions on policy-making, and of the provision on executive privilege – both of which were in the 2010 and 2011 versions proposed by the Palace – a provision exempting national security matters from public disclosure could be problematic if passed in its present form. The defense and military establishments – whose representatives came in force during the September 4 Senate hearings on the bill – have their fingerprints all over this provision.

An earlier version filed by Congressman Tañada limited related exceptions only to such information on national defense as troop deployments, military strength, and similar data. Because national security can be so broadly defined as to include practically every form of government-held information, this particular exception can have implications wide-ranging enough to defeat the bill’s purpose.

Human rights, free expression, and press freedom are among the likely casualties of this provision. Because most of the human rights violations in this country are committed in the course of the anti-insurgency campaign, citizen access to government records of human rights violations committed by the police and military could be denied on national security grounds. So could information on the inclusion of journalists and political activists in military Orders of Battle, as well as the listing of journalists’ and other groups’ among the “enemies of the state.”

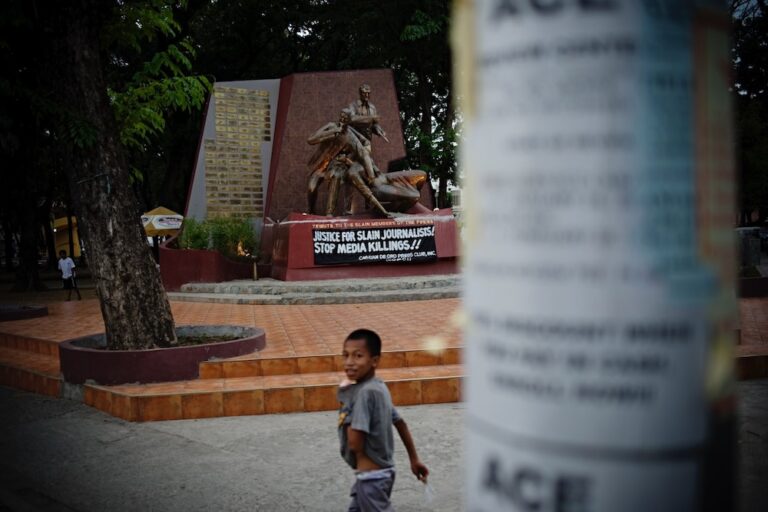

Both have happened before and could still be happening. In 2009 then New York Times and International Herald Tribune correspondent Carlos Conde found out that he was in the military’s Order of Battle, while the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines, the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, and the College Editors Guild of the Philippines as well as a number of such sectoral organizations as labor and farmers’ groups were among those organizations listed among “Enemies of the State”. These listings occurred in the context of a surge in extrajudicial killings and the number of journalists killed.

Information on whether one is in the military Order of Battle, or one’s organization is in the list of Enemies of the State, is in 2013 still crucial to journalists’ and ordinary citizens’ being forewarned about the perils to life and liberty they could face, to find out the reasons for their inclusion, and to doing something to have themselves removed from such listings. The work-related killing of journalists is continuing, as is the killing of human rights defenders, environmentalists and those involved in other advocacies. Information on one’s inclusion in such lists, and why, is information that could help prevent harm not only to journalists but to other citizens whose being so listed could have been based on mere suppositions of involvement in armed movements despite their being legal, above-ground personalities, but which inclusion could be an invitation to extrajudicial murder.

While among the fears that have been expressed about the FOI bill is how far the legislative process would water down its provisions, and whether additional exceptions will be inserted into it as to make it ineffective, what is equally central is subjecting the existing list of exceptions to the closest and most rigorous scrutiny to assure the passage of a law that would be truly contributory not only to the enhancement of the rights of citizens but also towards helping assure their physical safety. In the Philippine context, an FOI bill, depending on what its final form will be, can function towards that necessary purpose, or its very opposite.