In the United Arab Emirates, a series of show trials and convictions against online activists highlight an authoritarian regime’s attempts to quell growing dissent among a repressed citizenry.

By Rori Donaghy, co-founder and director of the Emirates Centre for Human Rights, the first independent human rights group focusing on the United Arab Emirates.

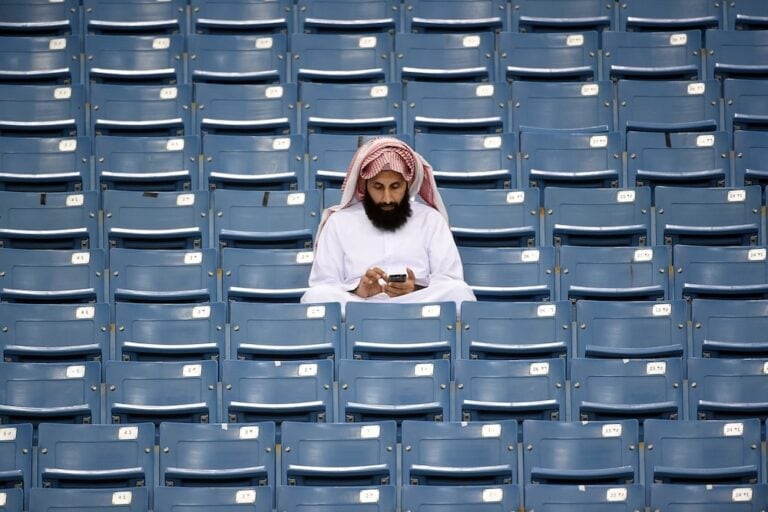

The measure of an effective police state is one where violence is used sparingly and fear is saturated across the population. A regime attempting to achieve this is in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), where a series of show trials and convictions against online activists highlight an authoritarian regime’s attempts to quell growing dissent among a repressed citizenry.

On Monday, 18 Nov, Waleed al-Shehhi was sentenced to two years in prison and fined 500,000 dirhams (£84,600) for using Twitter to question the handling of a political trial by authorities. He was convicted of violating the Cybercrimes Decree, which was passed in November 2012 and outlaws the use of information technology to, among other things, criticise actions of the state.

The cybercrimes decree has been decried as a piece of legislation that restricts free speech. It does not function as a piece of legislation, however, but as a strategically deployed tool to warn citizens of topics that are not acceptable discussion points. In the case of Waleed al-Shehhi, the redline topic was his questioning of authorities’ failure to investigate allegations of torture against political prisoners.

Al-Shehhi is the second person to be convicted of violating the cybercrimes decree, with the first, Abdulla al-Hadidi, recently released after serving a 10-month prison sentence. In the case of al-Hadidi, he was convicted of ‘spreading false information’ about a trial of political dissidents from which foreign media and international human rights groups were barred from attending. The redline topic in this instance was the spreading of information the state wished to keep secret; namely, the torture of political prisoners and details of a trial described by the International Commission of Jurists as “manifestly unfair”.

In both cases the online activists have been convicted of discussing a political trial. In the same way that the cybercrimes decree has been used strategically, authorities have accused those deemed most likely to be the source of a challenge to their autocratic power of seditious crimes.

After a petition was sent to the president in March 2011 calling for an accountable parliament, authorities prosecuted 5 liberal activists for insulting the rulers. After this, there was a trial of 94 political activists accused of attempting to ‘seize power’. There is also an ongoing trial of 30 Egyptians and Emiratis accused of establishing an illegal branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. Each trial has been marred by accusations of torture, arbitrary detention and a severe lack of due legal process.

However, as the Emirati authorities are finding out, the problem with arresting online and political activists is that with each unfair trial several, new Twitter accounts pop up to criticise the state. Whilst many citizens will be frightened of criticising authorities, there are others who remain steadfast in their commitment to expose the inequities of the state. Although the internet faces many challenges in meeting its emancipatory expectation, for those who are using it to challenge authoritarian regimes it remains a platform that their oppressors cannot fully co-opt. The UAE is trying hard to stamp out even the mildest form of dissent, but the paradigmatic shortcomings of a pre-internet police state theory have rendered their efforts a failure. As Dr. Christopher Davidson, author of After the Sheikhs, says: “the recent introduction of very punitive anti-free speech legislation, often specific to difficult-to-censor cyber activities such as social media, is being used to put people off spreading wider discussion of these human rights abuses in an arena that the authorities are ultimately unable to police”.

Active Twitter hash-tags ensure that debate of repression in the UAE remains vibrant. There is already an active discussion about the imprisonment of Waleed al-Shehhi and an 18-month long discussion calling for political prisoners to be freed continues unabated. As long as authorities allow citizens free access to social media websites their legislative attempts to silence dissent are likely to be futile. Indeed, should the day come when they deem it necessary to block such platforms, it could spark widespread civil disobedience in a country that has largely avoided the upheaval of the Arab Spring.

This article was originally posted on 21 Nov 2013 at indexoncensorship.org