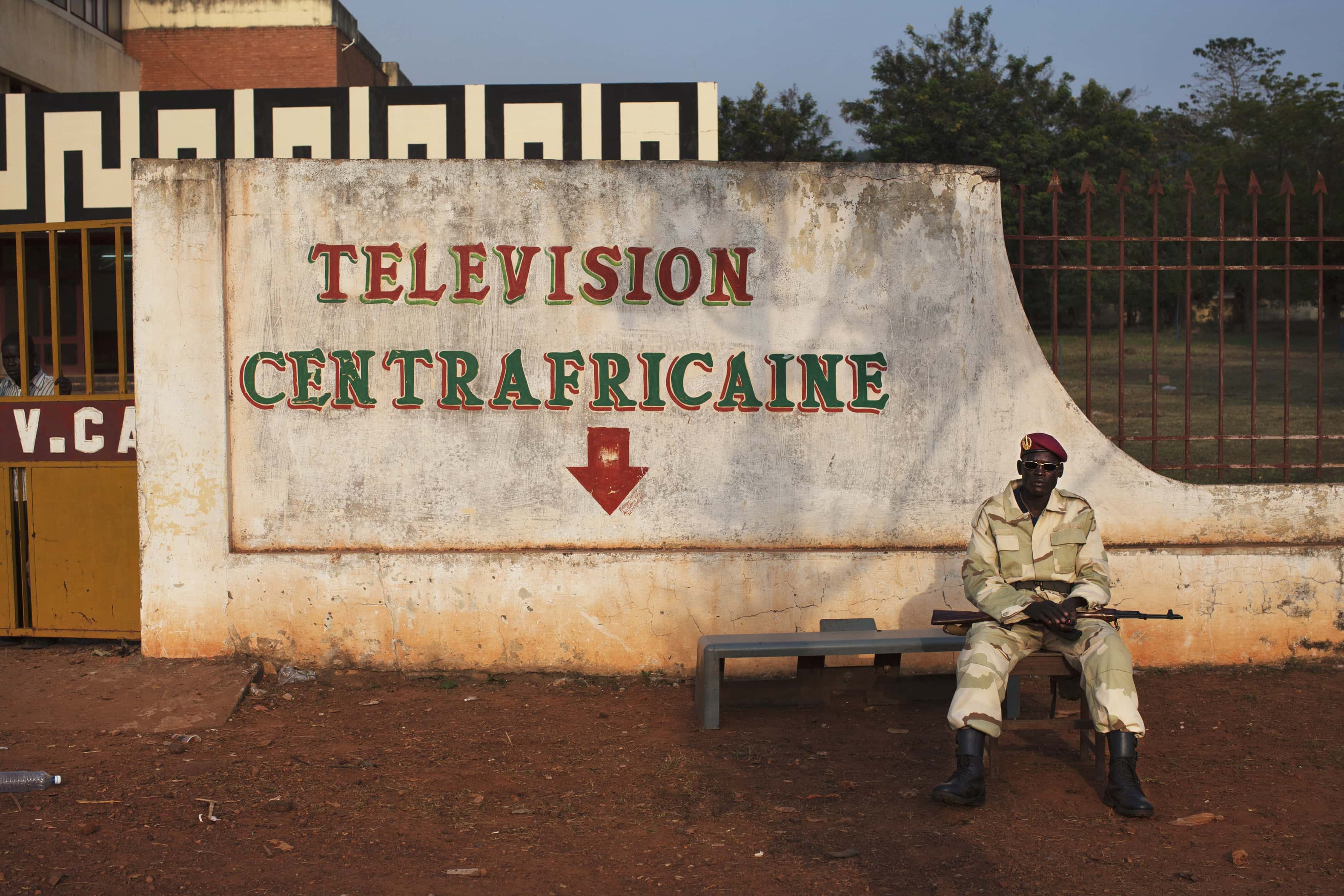

A year after the Seleka coalition began its rebellion, reporters in the Central African Republic are still in danger despite the deployment of French and African peacekeepers. Some media outlets have been ransacked, while others have self-censored their reporting to prevent threats or attacks.

A year after the Seleka coalition began its rebellion, Reporters Without Borders is providing the following overview of media freedom in the Central African Republic, where journalists are still in danger despite the deployment of French and African peacekeepers. Virtually none of the Bangui-based newspapers has published since 20 December because of the mounting violence and unrest.

The media landscape had gradually normalized in the course of the decade preceding the rebellion thanks to the relative stability imposed by President François Bozizé’s government.

There was notable legislative progress in 2005, including the promulgation of a law on media freedom, the decriminalization of media offences and the creation of a regulatory body called the High Council for Communication.

The country’s news media nonetheless continued to experience the usual problems resulting from financial insecurity, a lack of equipment and training, and harassment by government officials.

The past decade’s evolution was brought to an end by the emergence of the disparate Seleka rebel coalition leading to the taking of the capital, Bangui, on 24 March 2013 and President Bozizé’s overthrow.

The situation has worsened since the events of 5-6 December, when coordinated attacks allegedly carried out by “anti-balaka” Bozizé supporters triggered violent reprisals by former Seleka militias, a process accompanied by growing polarization around religious identity – the “ex-Seleka” being mainly Muslim and the pro-Bozizé forces being mainly Christian.

Partisan coverage

As physical attacks and threats to media and journalists increased during 2013, many newspapers radicalised their discourse and failed to maintain journalistic objectivity.

In an attempt to prop up Bozizé’s crumbling regime, Radio Centrafrique and other state-owned media at first targeted the Seleka rebels with divisive messages and hate messages. Radio Centrafrique subsequently concentrated on broadcasting details of Seleka exactions.

Christophe Gazam Betty, the communication minister appointed after the Seleka takeover, banned the media from talking about Seleka’s actions, notifying them that every report needed authorization by his office and reminding the state media that they were required to support government policy under an existing decree.

The print media’s behaviour has been dominated by financial interests, with the main newspapers such as Le Citoyen, Le Confident and Hirondelle allying themselves with the politicians who offer them the most money.

Radio Ndeke Luka, a radio station supported by Fondation Hirondelle, a Swiss NGO, and by international donors, is the only news outlet to have remained relatively neutral during this period, limiting itself to reporting atrocities without comment.

Intimidation and physical attacks

When Seleka was in the process of taking Bangui in March 2013, its gunmen targeted the news media. The headquarters of many media were completely ransacked and equipment was even taken from Radio Ndeke Luka despite its privileged location within the compound used by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

“We often receive threats from Seleka members, either by telephone or they come directly to the station,” Radio Ndeke Luka editor Sylvie Panika told Reporters Without Borders.

Community radio stations in the centre of the country had to close as the Seleka forces advanced. Pressured either by local officials or by the rebels and increasingly exposed to violence, the radio stations were forced to stop covering the fighting. Those that tried to resist were silenced or ransacked.

After Seleka had ousted the Bozizé government, Reporters Without Borders urged the new authorities to ensure that the media were able to operate freely and safely.

Despite interim President Michel Djotodia’s promise on 3 May, World Press Freedom Day, that “no journalists will be imprisoned for speaking out” and that “they will be guaranteed this (..) freedom of expression by the new authorities,” there were many threats from government officials and Seleka members during the following months.

Government harassment and intimidation of privately-owned media increased in late July and in August. One journalist was kidnapped for several hours on 3 August and others were threatened by government representatives.

The announced disbanding of Seleka in September did not take place in practice and just helped to increase the dangers for the media. A new secret police force led by former Seleka general Mahamat Nouradine Adam began systematically harassing media personnel in October, arbitrarily detaining and threatening the editors of three Bangui-based dailies.

December crisis

The clashes in Bangui on 5 and 6 December, coinciding with the deployment of French troops with a UN mandate to disarm the ex-Seleka militias, plunged the country into a news blackout. All radio stations stopped broadcasting and newspapers stopped appearing for several days.

The three leading Bangui-based radio stations – Radio Ndeke Luka, Radio Centrafrique and Radio Notre Dame – resumed broadcasting on 8 December at the behest of President Djotodia, who summoned journalists to his office to record and broadcast his appeal for calm.

But the threats have not stopped. In at least one case, ex-Seleka militiamen who were supposed to be escorting media personnel threatened radio journalists and deposited them outside their station. Radio stations continue to restrict their broadcasting times in order to respect the 6 p.m. curfew.

Newspapers took more time to resume operations because of the difficulties of printing and distributing in the paralyzed city. Some newspapers, including Le Citoyen, Le Confident and Le Quotidien de Bangui, began publishing again on 16 December but Le Citoyen had to move to a safer location.

In the rest of the country, a few community radio stations have resumed broadcasting, mainly carrying appeals for calm. Local media are continually threatened.

The four journalists working at Radio ICDI, which is based in Boali, 95 kms north of Bangui, were forced to abandon the radio station and flee when ex-Seleka gunmen went to the station and threatened them on 16 December.

Radio ICDI is the only station covering a vast area to the north of the capital, relaying information from other radio stations to towns and villages that are now isolated from the rest of the country.

Because of the dangers, some media are taking great care with the way they are reporting the news, and in some cases are censoring themselves. Le Citoyen says it prefers to reproduce Radio France Internationale’s reports rather than provide its own coverage.

Journalists continue to be threatened and those still covering the clashes are clearly taking risks to do so. A foreign media crew was threatened by both ex-Seleka and anti-balaka militiamen last week and had to be escorted by French troops. It is assumed that any act of reporting entails taking a political position. Journalists, especially local journalists, are under threat from both sides.

Increased tension in the past few days forced almost all of the newspapers in the capital to stop publishing again on 20 December. Some journalists have told Reporters Without Borders that they feel that the threats to media personnel are growing by the day.

Reporters Without Borders’ recommendations

Reporters Without Borders recommends:

- that the Central African Republic’s media refrain from using a violent or polarizing discourse, that they report the facts without distortion and that they try to defuse tension and promote dialogue in order to prevent further escalation in the violence.

- that armed groups stop threatening journalists and respect their status as non-combatants and their role as neutral witnesses of events.

- that the transitional authorities continue to encourage the media’s activities so that they can inform the population about political and security developments.

- that the international forces deployed in the CAR protect journalist in line with UN Security Council Resolution 1738 on the protection of journalists in conflict zones.

Yves Mbonzi Damanzi, a technician at the national radio station, poses for a picture in his office at the radio headquarters in Bangui, Central African Republic, November 28, 2013. The studio was looted for its computers and recording equipment during the March 2013 coup.REUTERS/Joe Penney