The Philippines' controversial Cybercrime Prevention Act has been attacked by journalists and rights groups who oppose its draconian legislation, in particular, the libel provision that criminalizes anonymous online criticism.

[Accessing] any part of a computer system without right. Cyber-squatting. Cybersex. Computer-related forgery. What do these things have in common? They are all punishable acts under Philippines’ Cybercrime Prevention Act.

EFF has closely followed the Philippines Republic Act No. 10175, also known as the Cybercrime Prevention Act, since it was passed in September 2012. This controversial Act has been attacked by journalists and rights groups who oppose its draconian legislation, in particular, the libel provision that criminalizes anonymous online criticism. In October 2012, activists in the Philippines took to social media and – taking a cue from the PIPA/SOPA protests – campaigned for website blackouts to encourage action against the law. Then in 2013, a crowdsourced document called the Magna Carta for Internet Freedom was brought to the Senate that, if passed, could have repealed the Act.

These efforts did not go unnoticed; in February of this year, the Supreme Court of the Philippines tempered segments of the Act, declaring certain provisions – including posting a link to libelous material – unconstitutional.

The recent decision by the Philippine Supreme Court deemed the following sections of the Act unconstitutional:

- Unsolicited Commercial Communications. – The transmission of commercial electronic communication with the use of computer system which seek to advertise, sell, or offer for sale products and services are prohibited;

- Restricting or Blocking Access to Computer Data. – When a computer data is prima facie found to be in violation of the provisions of this Act, the Department of Justice shall issue an order to restrict or block access to such computer data;

- Real-Time Collection of Traffic Data. – Law enforcement authorities, with due cause, shall be authorized to collect or record by technical or electronic means traffic data in real-time associated with specified communications transmitted by means of a computer system.

To summarize, sending spam cannot be considered a crime; the Department of Justice cannot restrict access to or block websites without a court order; and the government cannot monitor phone or internet use in “real-time” without prior court order or warrant.

While this ruling is a step in the right direction, the Supreme Court did ultimately uphold the constitutionality of the Cybercrime Prevention Act as a whole, meaning several articles and provisions that pose a threat to freedom of expression and speech still remain – specifically the law on libel, the one act with which most rights groups are particularly concerned.

The Internet libel provision was upheld by the Philippine Supreme Court, but was distinguished by one important exception from the original law – that only the original author of libelous content can be punished by law, not the recipients who react to, like, or share said libelous content.

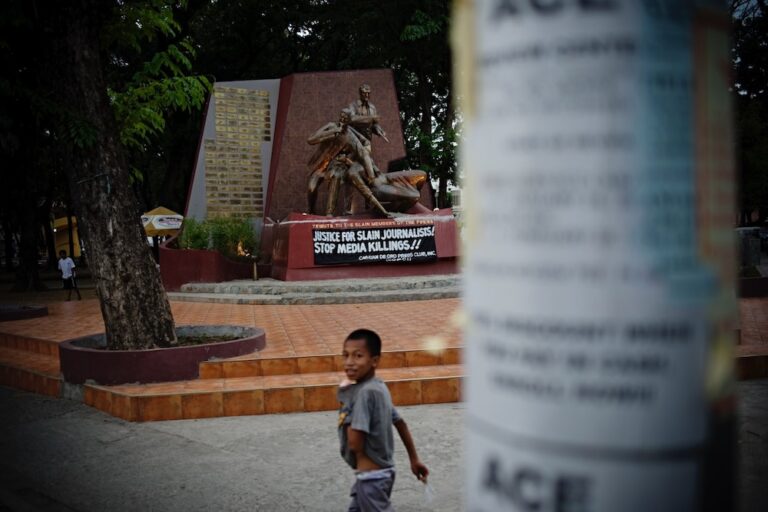

Even with this revision, censoring anonymous online criticism is a slippery slope. Many media organizations are working to decriminalize libel in the Philippines. According to the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism blog, “The Philippines is one of few countries in the world where libel is considered a criminal offense punishable with a prison term. Libel in the Philippines is also unique in that an allegedly libelous statement is presumed to be tainted with malice until the accused proves otherwise.”

Unfortunately, such laws are more common than the Center suggests: Russia, Venezuela, Azerbaijan, Albania, India, and South Korea are just a few of the countries that still consider defamation and libel a criminal offense punishable by imprisonment.

Although the Supreme Court’s recent decision on the constitutionality of the Cybercrime Prevention Act provides drastic improvements over the Act’s original text, the still highly controversial law continues to worry rights groups about the current state of Internet censorship in the Philippines. Some Filipino politicians seem to be tipping more and more towards Internet censorship – as seen through the recent legislation that requires Internet service providers to install filters to block access to child porn. Granted, the Philippines hasn’t landed on the Reporters Without Borders’ “Enemies of the Internet” list, yet, however it’s certainly a country on which we’re keeping watch.