Over the past four years, Hungary has seen dozens of small, and not so small, encroachments on the right to free expression. Taken en masse, certain developments in Hungary indicate a clear trajectory towards authoritarian regulation of the media, and the situation is becoming increasingly dire.

By Diane Shnier

“Soft censorship,” including actions such as quiet dismissals, punitive tax laws, denied radio frequencies and abuse of privacy legislation, is arguably the most worrisome type. It creeps and grows in small increments and therefore often goes unnoticed until it has become institutionalized, at which point it is difficult to reverse. Over the past four years, Hungary has seen dozens of small, and not so small, encroachments on the right to free expression. Taken en masse, certain developments in Hungary indicate a clear trajectory towards authoritarian regulation of the media, and the situation is becoming increasingly dire.

The current troubles in Hungary date back to April 2010, when centre-right Fidesz party was elected and Viktor Orban became Prime Minister. Due to the design of the Hungarian electoral system, the Fidesz party received just over 50% of the vote, yet gained over two-thirds of the seats in parliament. This supermajority meant they were able to pass sweeping changes quickly, without time for public consultation and without meaningful opposition from other parties. Over the next few years, the Fidesz-dominated Hungarian parliament pushed through 600 laws, reforming (and in the process, centralizing) health care, education, agriculture, the judiciary, and of course the media.

Among the most controversial of these early reforms is the Media Act, which was passed by the Hungarian parliament in December 2010. The Act allows a newly created “Media Council” to fine media outlets for a number of nebulous offences, including failure to “provide balanced coverage,” publishing news that is “insulting to communities,” or in contempt of broad ideals such as “public morality.” The Media Council, entirely composed of members appointed directly by the Fidesz party for nine year terms, is solely responsible for interpreting these vague restrictions. Moreover, the restrictions are not limited to mass media outlets, but include personal websites and blogs. Nor are the restrictions limited to media outlets within Hungary; the Media Council has the power to obstruct domestic access to international news sources, so long as the content concerns Hungary. Offenders of the Media Act can be fined up to $928,000 USD.

In April 2011, the Hungarian parliament penned and signed into law a new constitution, or Fundamental Law, which many critics saw as a departure from European Union standards of democracy. There are numerous problems with this new constitution, including its vague human rights provisions, its alteration of the maximum age for retirement which forced 274 senior judges to resign, and the questionable democratic mandate under which Fidesz pushed it through parliament. However, most relevant to freedom of expression is that this new constitution significantly reduced the power of Hungary’s constitutional court. This body is responsible for keeping the Hungarian parliament in check and ensuring that legislation abides by the constitution, and is thus a staple of any well-functioning liberal democracy.

Since the passing of the 2011 constitution, the Hungarian parliament has repeatedly taken advantage of this weakened constitutional court to pass legislation that suppresses free expression. For example, in January 2013, political advertising was banned for independent media outlets, restricting political advertising to government owned media outlets only. Hungary’s constitutional court rejected this legislation as unconstitutional; clearly, such a law would impede political expression and is extremely vulnerable to government abuse come election time. However, in March 2013, the Fidesz party used their supermajority to override the weakened court by directly entrenching the ban on independent media political advertising in the constitution itself. This amendment also circumscribed the court’s powers even further by preventing it from rejecting any future legislation as unconstitutional based on its content. Instead, Hungary`s constitutional court is now only capable of striking down legislation on procedural grounds; for example, if the vote to pass legislation violates a parliamentary rule. Hungary`s enfeebled constitutional court essentially leaves the Fidesz-dominated parliament unchecked.

Yet, media censorship in Hungary is not limited to abuses of the constitution. In December of 2011, the Media Council revoked the frequency rights of the popular liberal talk radio station Klubradio. The council’s spokesperson gave no explanation, and refused to reveal the criteria by which radio frequencies are allotted. For the next two years, Klubradio operated on successive two-month licenses, which scared off advertisers and financially crippled the organization. It was not until March 2013, after four court rulings in favour of Klubradio, that the Media Council finally re-awarded the radio station its long term frequency. Klubradio director Andras Arato said, “The government doesn’t like to hear any criticism, so it tried to starve us to death.”

During Fidesz’s 2010-2014 term, there were many other violations of the right to free expression. In January 2012, Hungarian journalist Attila Mong was threatened with criminal prosecution for publishing a letter from EU Commission President Jose Manuel Barroso to Prime Minister Orban, in which Barroso questioned whether recently introduced Hungarian laws met EU standards. According to the Hungarian Interior Ministry, this letter was a “private matter,” and Mong’s publication of it on his blog violated the country’s privacy law. In June 2013, parliament passed a law limiting access to public information, reducing government transparency and impeding the ability of journalists to comment on and criticize government actions. In November of the same year parliament also passed a law which punishes the creation and distribution of recordings made to “harm another person’s dignity,” encompassing political commentary and satire, with up to three years in prison. The list goes on.

Since Fidesz and Orban’s re-election in April 2014 (by a lesser margin than the 2010 election), the government crackdown on media has become increasingly severe. On June 2, Gergo Saling, the editor of leading independent news outlet origo.hu was dismissed after publishing an article detailing the inappropriate business expenses of Janos Lazar, Chief of Cabinet to Prime Minister Orban. Thirty journalists subsequently resigned from origo.hu in protest.

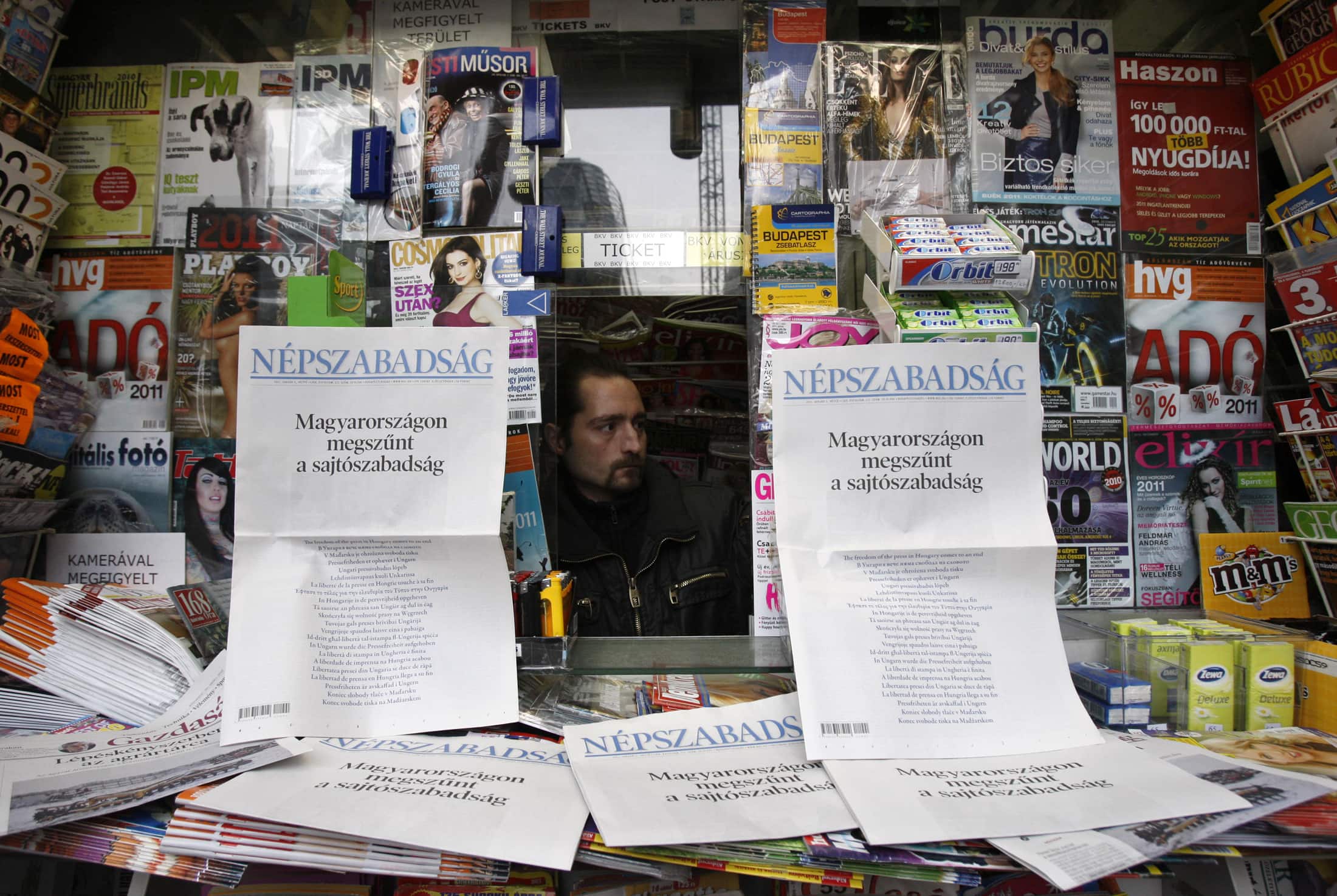

Later that same month, the Hungarian parliament passed a media tax, which applies to revenue earned from advertising. This tax is particularly damaging as it targets media outlets primarily funded by advertising, and therefore independent of government control (as opposed to those media outlets subsidized by the government). The progressive tax will charge Hungary’s largest news outlets 40% of their ad revenue; some media firms say the tax will bankrupt them. Hungarian media outlets joined together to protest the tax, printing newspapers with blank pages and halting broadcasts.

This same month, stemming from the infamous media laws of 2010, Hungary’s Supreme Court ruled that ATV, an anti-Fidesz television station, had defamed Hungary’s right-wing Jobbik party by referring to it as “far-right.” The Supreme Court ruled that such language might leave viewers with a negative opinion of the party and is therefore illegal, despite Jobbik being routinely described as far-right by other media outlets around the world, including BBC and The Independent.

As if three instances of blatant censorship aren’t enough for one month, a fourth incident also occurred in June. Government authorities raided the offices of three NGOs, demanding documents that the organizations had received from Norway. The raid followed the creation of a government list of “questionable NGOs” after Chief of Cabinet Janos Lazar accused Norway’s Minister for EU Affairs, Vidar Helgesen, of attempting to influence Hungarians to support Hungary’s left-wing party through NGO funding. Hegelsen says he is “deeply concerned about the actions of the Hungarian authorities in relation to civil society and their attempts to limit freedom of expression.”

When a government attacks free expression directly – when a journalist is arrested, or killed, or a media outlet is shut down – the world takes notice. Instances of “softer”, indirect censorship often fly under the radar, but are no less insidious. Press freedom in Hungary has markedly deteriorated under the rule of Fidesz and Orban, and it is vital that the world keep a close eye on the country as they begin their second term in power.

Diane Shnier is CJFE’s Outreach and Communications Assistant, currently completing her degree in political science at McGill University.