Reporters Without Borders has spotlighted eight cartoonists who are being threatened or persecuted because of their work.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 6 March 2015.

Ferzat in Syria, Dilem in Algeria, Vilks in Sweden, Zunar in Malaysia, Prageeth in Sri Lanka, Bonil in Ecuador, Kart in Turkey and Trivedi in India – all of these cartoonists have been threatened. Some have been targeted by radical groups, others by govenments that have tried to silence them by means of arrest and prosecution. Some are under both kinds of threat.

Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights says freedom of expression may be restricted to ensure “respect of the rights or reputations of others” or “the protection of national security or of public order, or of public health or morals,” but these restrictions must be proportionate in order not to violate the right to information.

At the same time, the UN special rapporteur on freedom of opinion and expression has stressed that the right to free speech includes the expression of opinions that “offend, shock or disturb.”

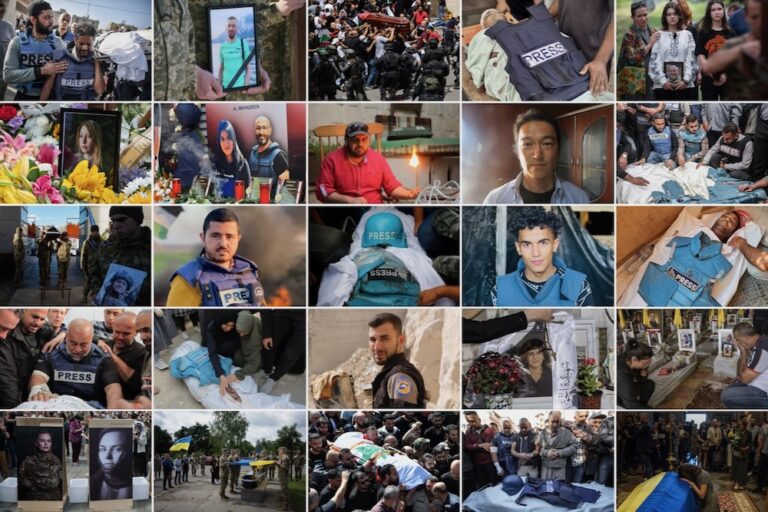

Regardless of international law, political, religious, business and military leaders and non-state groups often prove unable to tolerate criticism and derision. Censorship, dismissal, death threats, judicial harassment, physical violence and, in the gravest cases, murder are what an increasingly exposed profession faces.

Reporters Without Borders has looked at the cases of eight cartoonists who have been persecuted in connection with their work.

Ali Ferzat (Syria)

Armed intelligence officers kidnapped cartoonist Ali Ferzat in Damascus on 25 August 2011. He had been critical of the Baath Party and President Bashal Al-Assad for years but, after the start of the Syrian uprising, his cartoons had become bolder and had drawn attention to the regime’s mass murders. His abductors handed him over to government militiamen who crushed his left hand, the one he uses to draw, and used cigarettes to burn his skin all over his body.

They finally dumped him at a roadside a few hours later with a bag over his head. Aged 64, he now lives in exile in Kuwait, where he continues to work. He was awarded the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Expression in 2011.

Ali Dilem (Algeria)

Ali Dilem, who works for the Algerian daily Liberté and French TV channel TV5 Monde’s Kiosque programme, knows only too well that it’s not easy being a cartoonist in Algeria. He has been the target of death threats by Islamist groups and judicial harassment for years. He has had frequent spells in police custody and has received suspended jail sentences on criminal defamation charges. In 2001, he had the regrettable privilege of seeing his named used to label a series of amendments to the criminal code providing for sentences of up to a year in prison for journalists.

But he has never let up and has received a score of international prizes including the Press Freedom Trophy from the Limousin Press Club and Reporters Without Borders in 2005. France’s culture ministry honoured him with the title of Chevalier for outstanding achievements in the arts in October 2010.

Lars Vilks (Sweden)

Sweden’s Lars Vilks became known throughout the world after his Mohamed cartoons were published in 2007. Al-Qaeda issued an appeal to “shed the blood of this Lars who dared to insult our Prophet,” offering 100,000 dollars for his murder, 50,000 dollars for the murder of Ulf Johansson, the first newspaper editor to publish one of the cartoons, and another 50,000 dollars if Vilks was “slaughtered like a lamb.” The police protection he has received since 2010 was stepped up after the Charlie Hebdo massacre. A 50-year-old American woman convert to Islam who called herself “Jihad Jane” was sentenced to ten years in prison in 2014 for her role in a 2009 plot to kill him. Vilks was one of the presumed targets of the attack on the conference held in Copenhagen on 14 February 2015 to pay tribute to the Charlie Hebdo victims.

Zunar (Malaysia)

A book of cartoons by Malaysia’s Zunar (Zulkiflee Anwar Alhaque) was banned and his home was searched in 2010 in the first of many acts of judicial harassment. He said he just wanted to use his social and political cartoons to help people to “understand the news” but he was accused of sedition and he began a long legal battle to stop the government from censoring his work – a battle that is far from over. Malaysia’s electoral commission banned all cartoons during the campaign for parliamentary elections in 2012 in an attempt to head off criticism by him and others.

Since his conviction in July 2012, he can no longer hold an exhibition in his own country. In the latest twist, the police raided his Kuala Lumpur office on 28 Janary without showing a warrant, confiscated hundreds of his books and interrogated his staff.

Prageeth Eknaligoda (Sri Lanka)

Sri Lankan political analyst and cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda has not been seen since leaving his office to go home on the evening of 24 January 2010. He had told a close friend he thought he had been followed for the past several days. A week before his disappearance, he wrote a long article comparing the two leading presidential candidates and voicing a preference for the opposition one. For the next two months, the police showed no interest in finding him alive and provided the family with no significant information. Worse still, government ministers made contradictory statements and created confusion about the circumstances of his disappearance. The president’s brother, defence minister Gotabhaya Rajpaksa, went so far as to suggest in an interview: “Eknaligoda staged his own disappearance.” On the third anniversary of his disappearance, Reporters Without Borders and Cartooning for Peace launched an international campaign entitled “Where is Prageeth?”

Xavier Bonilla (Ecuador)

It’s tough being a cartoonist in Ecuador, where freedom of information is under attack a year after adoption of the Organic Communication Law (LOC). The Office of the Superintendent of Communication (Supercom), an entity created by the LOC, has repeatedly censored Xavier Bonilla, a cartoonist known as Bonil. Supercom decided in February 2014 that a cartoon criticizing a police raid on a journalist’s home had “defamed” the government and ordered Bonil to publish a correction.

It also ordered his newspaper, El Universo, to pay a fine of 90,000 dollars. Supercom was back on the offensive in early 2015. This time it accused Bonil of “socio-economic discrimination” in a cartoon mocking the limited oratorial skills of Agustín Delgado, an Afro-Ecuadorian ruling party representative who used to be a footballer. On Supercom’s orders, El Universo apologized to the country’s Afro-Ecuadorian community. Bonil got a written reprimand that told him to “correct his practices” and not cause further offence.

Musa Kart (Turkey)

Political caricature is a well established tradition in Turkey, as is persecuting cartoonists. Musa Kart, a well-known cartoonist employed by the daily newspaper Cumhuriyet (Republic), was charged with “insulting” then Prime Minister (now President) Recep Tayyip Erdogan in a February 2014 cartoon suggesting he was involved in the alleged money-laundering that led to the departure of four ministers.

Although a prosecutor initially dismissed the case, the all-powerful Erdogan managed to have new charges of “insult,” “violating the confidentiality of a judicial investigation” and criminal defamation brought against Kart, who was facing the possibility of several years in prison. British cartoonist Martin Rowson responded by launching a Twitter campaign with the hashtag #ErdoganCaricature that called on cartoonists worldwide to satirize Erdogan in solidarity with Kart. After the campaign quickly went viral, an Istanbul criminal court finally acquitted Kart in October 2014. But Erdogan has appealed, reviving the case yet again.

Aseem Trivedi (India)

Indian cartoonist Aseem Trivedi began participating in the anti-corruption movement in 2011, launching a site called “Cartoons against Corruption.” After showing his work at an anti-corruption meeting, he was arrested in September 2012 on sedition charges for parodying India’s national symbols and spent several days in prison. The same year, he and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat received Cartoonists Rights Network International’s Courage in Editorial Cartooning Award. Trivedi then took a two-year break from cartooning which he ended after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, publishing a cartoon strip entitled “Because” that showed the Prophet Mohamed. He said he did so because of the importance of overcoming the fear felt by all cartoonists after the massacre. Facebook removed it and then reinstated it.

He has also launched a “Cartoon Against Every Lash” campaign in support of Raif Badawi, the Saudi blogger sentenced to 1,000 lashes and ten years in prison, and is planning to launch a satirical weekly about society, politics and religion with the work of several Indian cartoonists. Its first issue will be dedicated to Charlie Hebdo.

AP Photo/Muzaffar Salman

Twitter / Ali Dilem

AP Photo/Bjorn Lindgren, File

AP Photo/Joshua Paul)

A man holds a placard with an image of missing cartoonist Prageeth Eknaligoda during a protest in Colombo in 2010REUTERS/Dinuka Liyanawatte

Facebook / Xavier Bonilla

Twitter / Musa Kart

Cartoonist Aseem Trivedi gestures after he is arrested in September 2012 by the police on charges of mocking the Indian constitution in his drawings AP Photo