Murders, media bans and surveillance laws put growing pressures on civil society in Asia.

Civil society groups have been having a tough time in Cambodia.

On 10 July 2016, Cambodian activist and political commentator Kem Ley was shot dead in Phnom Penh, the attack believed to be linked to his work and critical position against the government. A few days before his killing, Kem Ley appeared on a radio show to discuss an exposé by Global Witness that reported on Prime Minister Hun Sen and his family’s stranglehold on many key economic sectors in the country.

Colleagues and observers say that Kem Ley was a respected political activist who had worked tirelessly to support grassroots advocacy. The Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR) and the Cambodian Centre for Independent Media (CCIM) were among the many local non-governmental organisations that condemned Kem Ley’s murder, raising concerns over the deteriorating spaces for civil society and deadly attacks against free expression. IFEX members signed a letter calling on the Cambodian government to support civil society and ensure investigations into the killing.

Activist Ou Virak, himself a target of defamation charges by the ruling party for his commentaries in May, tweeted this following reports of Kem Ley’s killing:

“It’s going to have a chilling effect, and I don’t think there will be anyone who will replace him any time… https://t.co/GxCKhDlTOs

— Virak Ou (@ouvirak) July 11, 2016

Threats to NGOs and civil society actors have escalated in a number of countries across Asia and the Pacific, among them the arrests of activists opposing the referendum in Thailand and supporters of the West Papua freedom movement in the Pacific.

The UN Human Rights Council made a strong stand this July as it adopted a resolution calling for more protection for civil society. Among others, the resolution commits states to ensure access to justice and accountability and to end impunity for human rights violations and abuses against civil society actors. International NGOs, including ARTICLE 19, welcomed the resolution.

Press freedom

In India, police raided media offices in Jammu and Kashmir on 16 July and prevented them from printing their newspapers. The ban was put in place after a major anti-India protest following the shooting of a young rebel leader in the disputed region of Kashmir.

The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) and its affiliate, the Indian Journalists Union (IJU), strongly condemned the raids and ban, which prevented the public from accessing crucial information, and argued that the moves were unconstitutional.

Online media reported that the ban was lifted after three days, with officials saying it was a mistake, but editors and owners remained uncertain as there were no clear guarantees their operations would not be affected. Read more here.

Shujaat Bukhari of Rising Kashmir, who was affected by the ban tweeted that he was not surprised by the excessive handling of the situation by the authorities:

BBC News – My Kashmir newspaper has been shut down, and I’m not surprised https://t.co/tBEnnMUq0m #Kashmir

— Shujaat Bukhari (@bukharishujaat) July 18, 2016

Freedom of expression laws

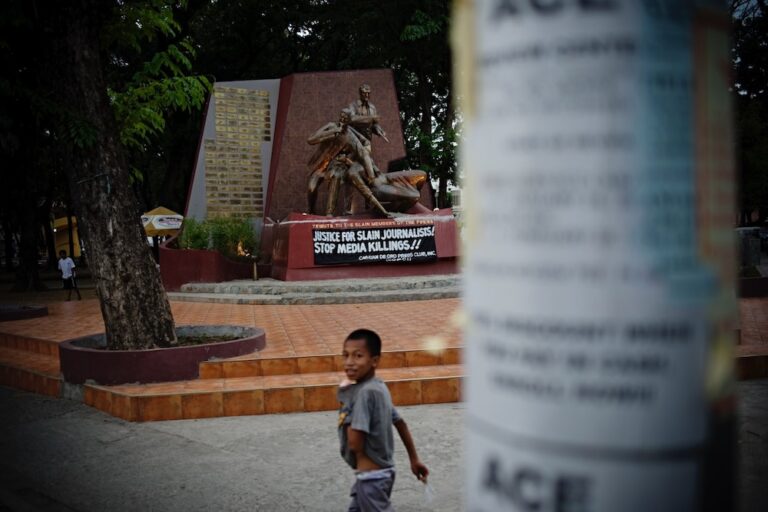

While the Philippines president has come under fire for his anti-media stand in relation to impunity and the “endorsement” of extrajudicial killings of suspected criminals and drug offenders, he drew applause for announcing an Executive Order for the implementation of freedom of information (FOI). The IFJ said it welcomed the announcement with caution.

#IFJ and @nujp cautiously welcome the executive order on #FOI signed by the new President last week in #Philippines https://t.co/tgkXiPs9No

— IFJ Asia-Pacific (@ifjasiapacific) July 26, 2016

Both the Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) and the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) noted that while the Executive Order met a number of the FOI principles, a legislation detailing full disclosure with limited exceptions was still needed.

In Pakistan, civil society groups have expressed concern over the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Bill that was eventually passed by the Senate on 29 July, as they claim it retains draconian provisions despite the inputs provided to strengthen safeguards and free speech guarantees. The Senate has passed the law with amendments which will now be sent back to the National Assembly for their deliberation.

Digital rights groups like Bytes for All and Digital Rights Foundation say the latest version of the bill ignored civil society inputs on matters such as surveillance, impact on free speech and the unclear definitions of hate speech.

Delighted to report that Parliamentary Reporters Group just walked out of session protesting #PECB @bytesforall @mmfd_Pak

— Shahzad Ahmad (@sirkup) July 27, 2016

Senators who had worked closely with civil society managed to include amendments to the law to ensure judicial and parliamentary oversights.

Still an imperfect #CyberCrimeBill but standing committee and other senators added 53 amendments adding unprecedented parliament oversight

— SenatorSherryRehman (@sherryrehman) July 29, 2016

Reports

The Hong Kong Journalists Association released its annual report for the period ending June 2016, noting major setbacks to press freedom in Hong Kong as a result of the “spillover to Hong Kong of mainland Chinese ideological control.”

The report investigates the ways in which mainland China under the leadership of Xi Jinping has increased controls over the island’s media and the increase of online news websites to counter critics of pro-establishment media.

In relation to this trend, the Committee to Protect Journalists expects that the new director of the Cyberspace Administration of China – Xu Lin – will tighten the government’s grip on the country’s information and internet controls, including online news sites.

#China bans internet news reporting as media crackdown widens @business #PENdigest #FreeExpression https://t.co/2zweVhiUb1

— PENamerican (@PENamerican) July 25, 2016

In this 23 Sept. 2015 file photo, Chinese President Xi Jinping, center, talks with Facebook Chief Executive Mark Zuckerberg, right, as Lu Wei, left, China’s Internet czar, looks on during a gathering of CEOs and other executives at Microsoft’s main campus in Redmond, WashingtonAP Photo/Ted S. Warren, Pool, File