In Chile, the protection of private life, private communications, and the sanctity of home lay the foundation that, in principle, provides individuals with sufficient protections from the abuse of both State and private actors.

This statement was originally published on privacyinternational.org on 4 November 2016.

The recent State of Privacy report on Chile shows a degree of stagnation in the field of policy reforms regarding privacy and personal data protection. At the same time recent developments have shown that risks to privacy continue to increase without proper public discussion or recourse for citizens.

By Juan Carlos Lara of Chilean organisation Derechos Digitales

In Chile, the protection of private life, private communications, and the sanctity of home lay the foundation that, in principle, provides individuals with sufficient protections from the abuse of both State and private actors. This framework, built on the Chilean Constitution and all human rights agreements of which Chile is part, also includes data protection law, specific safeguards for communication surveillance in criminal investigations, and penalises some privacy violations. But this framework, as shown in the State of Privacy report on Chile, has become stale and outdated in light of recent developments as well as current local and global trends.

From a public policy perspective, the outdated nature of the framework is most noticeable in data protection regulation, which consists of an outdated statute that was passed in 1999 and modified almost annually. Data protection law in Chile lacks proper consent rules, data protection authority, and effective procedures and sanctions against unlawful treatment of data. Although the current government has been drafting a new data protection bill for two and a half years, the draft bill has failed to enter Congress and no text of the proposal has been made publicly available.

This failure is only an expression of deeper problems with Chilean norms, which in turn reflects the sad state of affairs in the political arena. Discredited political actors from across the spectrum have failed to pass meaningful laws, and the lack of commitment by government allies prevents certain bills from even entering Congress. For example, an ongoing process to draft and approve a new Constitution which may include data protection (as the current Chilean Constitution is one of the few in the region without mention to personal data), is stalled and under heavy scrutiny by the opposing coalition.

And while laws become stagnant, new forms of collection and processing of personal and private data continue to thrive unopposed. Government surveillance capabilities are either actively being expanded or expansion is being sought, while rules passed long ago remain unfit to regulate or prohibit such activities. There are two recent situations which serve as examples of the obscurity of state surveillance and the ineffectiveness of the law.

The first example is the Hacking Team revelations from 2015, which revealed that an intermediary by the name of Mipolcar facilitated the sale and use of Hacking Team malware to the Chilean Investigations Police. Their admission, however, included the claim that the use of such technology was legal and authorised by courts. Due to continued secrecy, it remains unknown where the malware has been used.

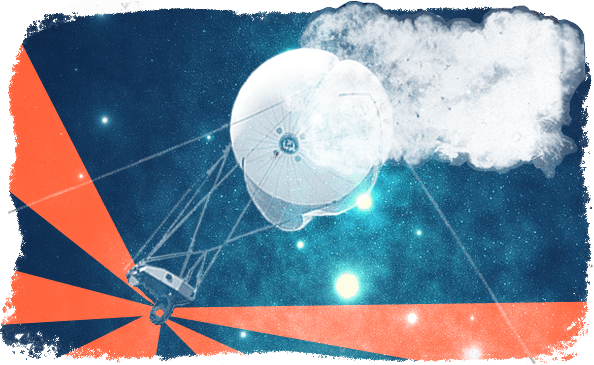

The second example is the use of three surveillance balloons since August 2015 by two municipalities in wealthy districts of Santiago, to film and monitor street level activity. The military-grade technology used by the municipalities allows for surveillance from up to a mile away, and has strong zooming capabilities, recording capabilities, and nocturnal vision. Similar balloons are reportedly also used in Afghanistan, the Gaza Strip and the Mexico-U.S. border. In this example, the balloons were installed in residential areas, where people could not only be followed and identified in the streets, but also in their homes.

Taking action against these balloons, several organisations on behalf of affected neighbours, filed a lawsuit on constitutional grounds against the two municipalities for their use of surveillance equipment, their violation of both privacy and the sanctity of home, as well as their collection of personal data without proper consent or legal authority. In the first decision on the matter in March 2016, the Court of Appeals of Santiago banned their use, but it was overturned on appeal. The Supreme Court, in its final ruling (case No. 18481-2016), recognised that this sweeping surveillance mechanism did indeed pose a threat to privacy and autonomy, but allowed their continued use provided some control mechanisms were put in place for the recordings and the access, use, and deletion of its records. Thus, rules and faculties that should be established by law and regulations, absent in this case, have been set by the judiciary with few or no mechanisms to enact proper safeguards.

In the end, it seems that the protection of the right to privacy in Chile is still too steep a price to pay when placed on the scales against the interests of the securitisation discourse and the incumbent market forces. But from the challenge arises an opportunity. Under these conditions, a sense of urgency for the protection of the privacy of Chile’s inhabitants continues to grow. The debates around seemingly unreachable milestones of a new Constitution, surveillance reform or a new data protection law, are also the opportunity to engage newer voices in policy discussions, to push political forces to move beyond party lines, and to help build a framework for the future of privacy and human rights, from the interest of citizens instead of State or corporations.