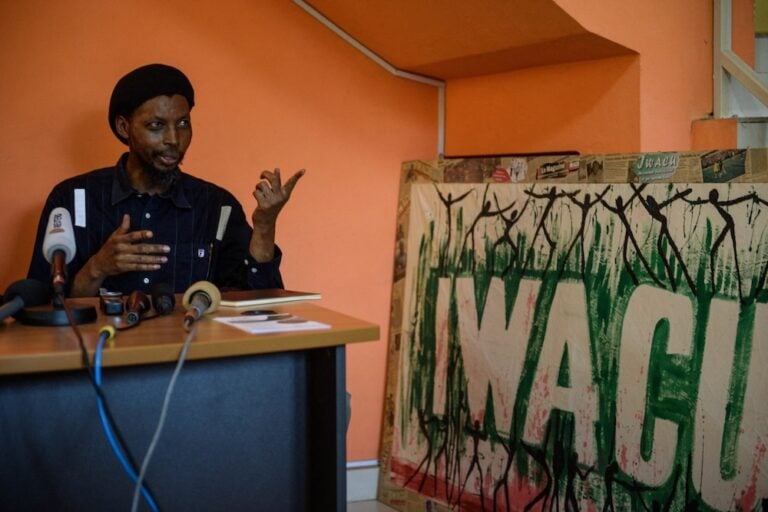

Burundi's National Intelligence Service has accused Radio Isanganiro editor Joseph Nsabiyabandi of stirring up public opinion and inciting revolt, without citing any specific report corroborates these accusations.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 6 April 2017.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is concerned about Radio Isanganiro editor Joseph Nsabiyabandi’s interrogation yesterday by Burundi’s feared National Intelligence Service (SNR) and, more broadly, about government meddling in the Bujumbura-based radio station’s editorial policies.

Nsabiyabandi spent the afternoon at SNR headquarters being questioned about his supposed collaboration with Radi Inzamba and Humura, two Burundian exile radio stations based in neighbouring Rwanda.

The SNR also accused him of not adhering to Radio Isanganiro’s established editorial policies and of stirring up public opinion and inciting revolt, without being able to mention any specific reportage or piece of news that would corroborate these accusations.

Nsabiyabandi denied all the accusations and pointed out that, since his appointment as the radio station’s editor in October 2016, he has not received any warning from the National Communication Council for bias or misreporting the news. As he was leaving the SNR agents threatened him with possible consequences, should he not change his behaviour.

Exile radio stations targeted

The regime had already made it clear at a news conference on 17 March that an offensive against independent media outlets was being planned. In particular, the government’s spokesman issued a warning to Bujumbura-based radio stations that were closed down and are now broadcasting from abroad.

The authorities appear above all to be targeting the exile radio stations in Rwanda: Humura, an offshoot of the old RPA, and Radio Inzamba, which is operated by journalists who used to work for Radio Isanganiro and Bonesha FM. Both broadcast their news programmes online and via WhatsApp.

Their very existence and their interviews of Burundians in refugee camps are an achievement. But they have had problems obtaining reliable information from Burundi and they have no access to government officials so they cannot get official reactions and cannot reflect all sides to some of the stories they report.

“This intimidation of Burundian journalists in Burundi over their alleged collaboration with exile radio stations is designed to make it even harder for these radio stations to work and to isolate them even more,” said Cléa Kahn-Sriber, the head of RSF’s Africa desk.

“The Burundian government should be interested in a democratic and pluralistic debate to which the media could contribute. On the contrary, the authorities seem to favour a single narrative, one that supports President Nkurunziza’s exclusive power.”

Internal pressure

Yesterday’s interrogation of Radio Isanganiro’s editor by the SNR seems also designed to intimidate journalists working for media outlets within Burundi, who are under constant pressure, including within their own news organizations.

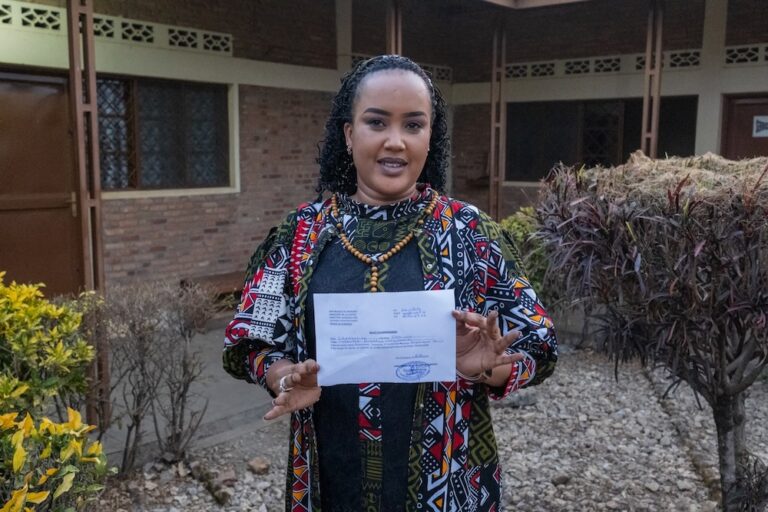

Radio Isanganiro is symptomatic of this situation. After being closed down like all the other independent radio stations in May 2015, it was allowed to reopen with Samson Maniradukunda appointed by a pro-government supervisory board as its new director, replacing Anne Niyuhire, who had fled to Rwanda.

To get permission to reopen, Radio Isanganiro had to sign an undertaking to pursue a “balanced and objective” editorial policy that respects the country’s “security.”

What “balanced and objective” means is left to the government and the new director, who makes it his job to implement government directives restricting the radio station’s editorial freedom. Sources close to the station say he has repeatedly intervened to get programmes changed after receiving calls from members of the government.

Radio Isanganiro’s journalists complain of being under constant pressure at work. Several of them were recently fired for defending their principles while those still there are alarmed by the fact that they have had to sign a new code of ethics.

In a country where the rule of law has been ignored for the past two years, where people can be arrested by intelligence officials and never reappear, and where everything is being done to tighten the regime’s grip on the population, the mere fact of having to sign a document at work can be very disturbing.

Burundi is ranked 156th out of 180 countries in RSF’s 2016 World Press Freedom Index.