The Syrian Telecommunication Regulatory Authority (TRA) announced that it may soon begin blocking voice and video calls on WhatsApp and other Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services.

This statement was originally published on globalvoices.org on 24 October 2018. It is republished here under Creative Commons license CC-BY 3.0.

This post, written by Grant Baker, was first published on smex.org. This edited version is republished on Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement.

On October 17, the Syrian Telecommunication Regulatory Authority (TRA) announced that it may soon begin blocking voice and video calls on WhatsApp and other Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) services.

The TRA said it would do this to increase revenues in the telecommunications industry, according to Al-Watan, a newspaper linked to the Syrian regime. The regulator’s general-director Ibaa Oueichek complained that VoIP “lowers the return on investment for [telecommunications] companies and reduces their incentive to make new investments to improve the network and offer better services for a lower price.”

Like other governments in the region, and in sub-Saharan Africa, the promise of increased revenues for locally administrated telecommunications companies is attractive, despite the burdens it would place on citizens.

If implemented, such a ban would increase the already-high costs of communication in the country and decrease flows of information. It would also present a threat to Syrians’ rights to privacy and would likely lead to greater self-censorship in the country.

Currently, two companies maintain a duopoly on Syria’s mobile telecommunication market: SyriaTel, owned by Bashar al-Assad’s cousin Rami Makhlouf, and MTN Syria, a subsidiary of the South Africa-based MTN Group Limited. The regime controls the internet infrastructure and bandwidth via two government agencies, the Syrian Computer Society (SCG) and the Syrian Telecommunications Establishment (STE). Founded by Bashar Assad, the SCG controls the country’s 3G infrastructure while the STE, which in 1999 commissioned the country’s first nationwide monitoring system, owns all fixed-line infrastructure. This allows the Syrian authorities to easily spy on users.

If WhatsApp and other encrypted VoIP services were to be censored, Syrians would have no choice but to use the government-controlled telecommunication services, leaving their private communications more vulnerable to government spying

This means that the Syrian government could easily listen in on their conversations and collect their communications metadata. It has been well-documented that the government purchases and uses various surveillance tools to spy on citizens. It is easy to imagine that if Syrians had no choice but to use local telecommunications services, authorities would take advantage of their relatively insecure technology and increase their habit of spying on the population.

Such a shift could also create a pathway for expensive and dangerous new alternatives. The United Arab Emirates government, which bans VoIP services including Skype, Viber and WhatsApp, has only allowed the country’s two mobile operators, Etisalat and Du, to roll out their own VoIP services. Not only do these services cost money, but the government of the UAE also has access to customers’ metadata and call information, which facilitates surveillance.

In an effort to increase profits, the telecommunications companies in Syria could roll out similar services. The new services might give citizens the illusion that their communications were protected, when in reality they would be just as vulnerable as regular calls.

While users in Syria could still circumvent this ban by downloading a VPN, this will exclude those who are not tech savvy and who have limited financial means. Most VPNs cost money and those that are free often track browsing and give third parties access to user data, creating added vulnerabilities for users.

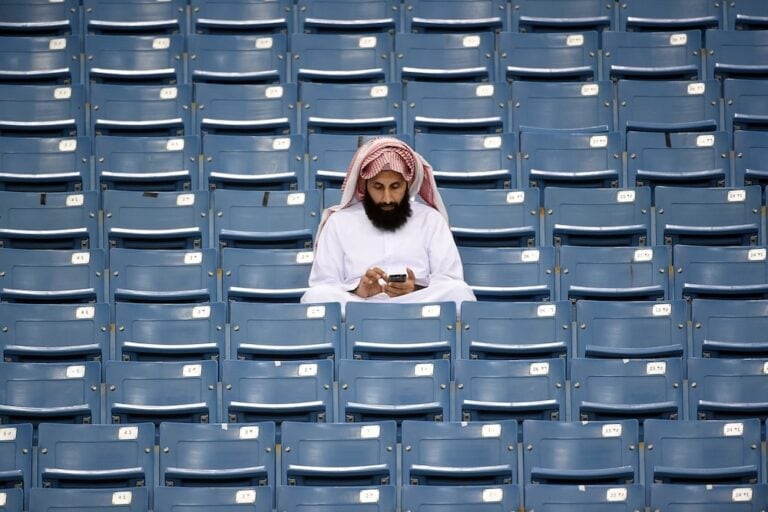

If the telecom industry regulator approves the blocking of VoIP services, Syria will be the latest country in the region to adopt such a restrictive policy. In addition to the UAE, Qatar currently blocks access to VoIP services, while Saudi Arabia still bans Viber and WhatsApp after easing its restrictions on the use of VoIP apps last year. Other countries in the region, like Lebanon and Morocco, briefly blocked access to VoIP in 2010 and 2016, respectively but quickly ended these initiatives.

Written by SMEX