Print and radio journalists from Sabah are pushing for media reforms in Malaysia, as well as passage of a Freedom of Information Act.

This article was originally published on seapa.org on 12 January 2018.

Print and radio journalists in Sabah are pushing for media reform as well as passage of a Freedom of Information Act, building on the campaign promises of the Pakatan Harapan, which now controls Malaysia’s new government.

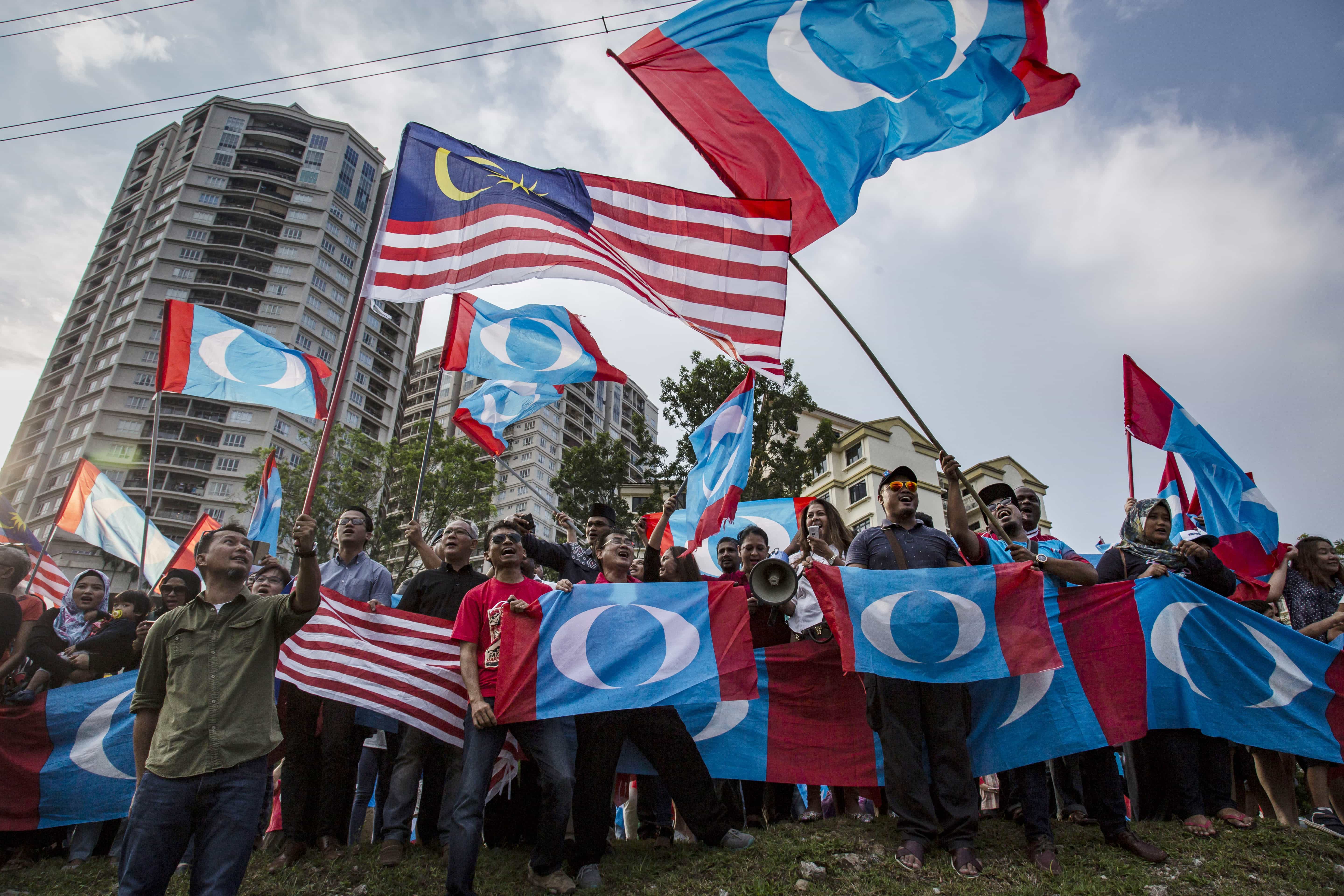

The party ran on a platform of reform during the last elections campaign and dealt a severe blow to the once ruling coalition, Barisan Nasional, during the historic 9 May 2018 vote.

A group of local journalists met earlier this month with the Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) director Sonia Randhawa in Kota Kinabalu to discuss the prospects for media reform in their state, located north of Borneo island.

They tackled the importance of a voluntary media council to protect editorial independence from both government and media owners, who may be political parties, commercial entities, or individuals. They also explored ways in which the media council could be funded, whether wholly by government, or with contributions from members.

The state government of Sabah has expressed support for a voluntary Media Council driven by journalists and editors. During the meeting, held in early October, it was emphasized that the media council exists to serve the members — composed of media organisations, individual journalists, and bloggers — to help ensure that they maintain and uphold the highest ethical and editorial standards.

Further, it was stressed that the media council should act as an intermediary between the media and the public, helping to mediate conflict between the two in an impartial fashion, thus helping to both restore and maintain public confidence in journalism.

In the same meeting with CIJ, journalists recognized the importance of the repeal of the Printing Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) as a prerequisite to the setting up of a media council. Under the PPPA, the relevant minister can suspend or withdraw the permit for a newspaper.

They agreed that wielding such power means that, despite efforts by individual journalists and editors, the newspaper’s survival depends on keeping the minister, and by extension, the government, satisfied with editorial output, at the expense of the public interest. This kind of situation undermines the pursuit of ethical journalism that fulfills the fundamental imperative of putting the public’s right to information at the heart of editorial decisions.

The meeting also highlighted the importance of East Malaysian representation in any national bodies governing the media.

CIJ hopes that a voluntary media council will pave the way for meaningful legislative reform, including the repeal of the Sedition Act and the PPPA in the current Parliamentary sitting, and the initiation of wide-ranging consultations on both freedom of information and the reform of the Communications and Multimedia Act, which governs broadcasting and internet provision.

To date, the Cabinet has passed a moratorium on the implementation of the Sedition Act, but appears noncommittal to both the repeal of the PPPA and legislating for freedom of information.

Malaysian law provides for a licensed print media, with licenses subject to strict control; has a broadly defined Sedition Act; and has an Official Secrets Act, which prevents public scrutiny of information, including contracts and environmental data.

The Malaysian government has promised to repeal the act governing print media, the PPPA, and the Sedition Act, as well as pass a Freedom of Information Act.