Misdiagnoses, missed operations, and the odd joke; Zimbabweans share how losing the internet affected them.

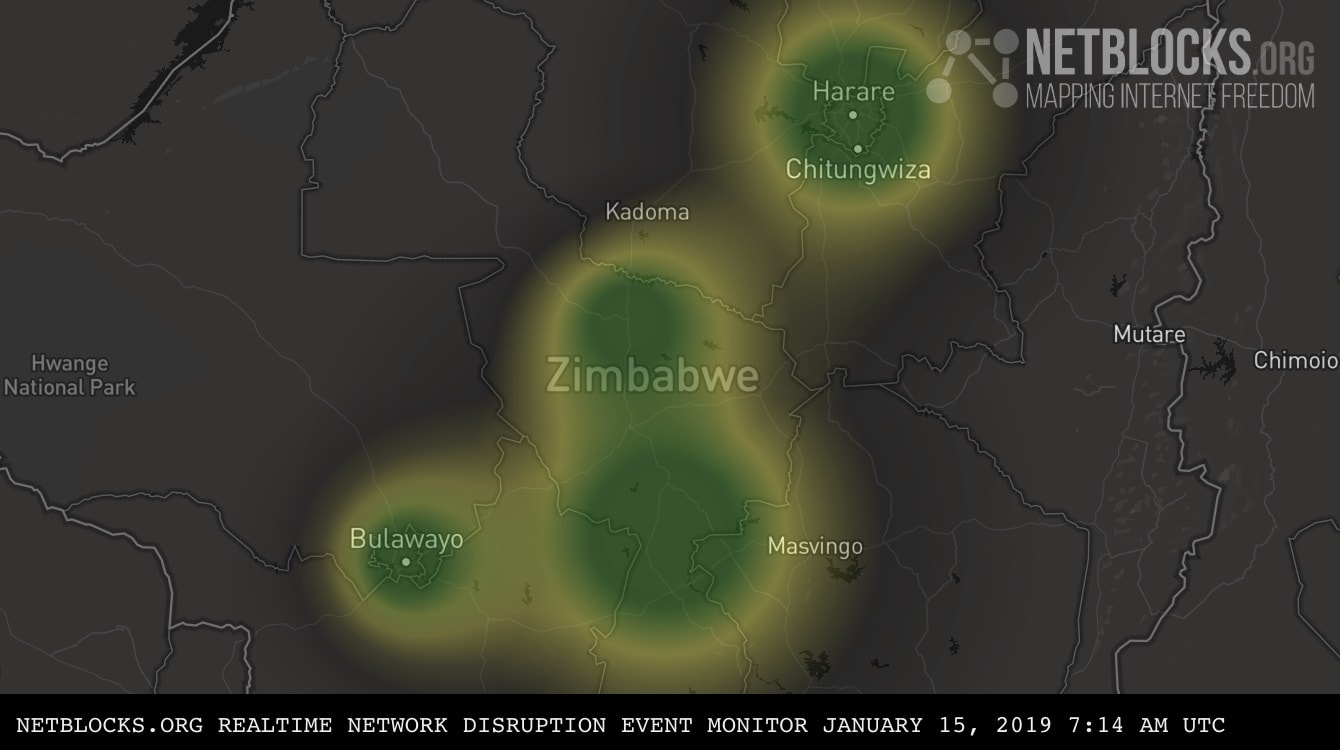

On 15 January, 2019, Zimbabweans woke up to a complete internet shutdown. All-too-familiar with connectivity problems, at first people tried to figure what was wrong with their network, or were surprised that power (often disconnected) was on, but internet was not accessible. It took a while before it dawned on people that the internet had been shut down.

“I felt disbelief, then frustration, and the final emotion I had before I gave in to the inevitable, was that of helplessness. It sank in that I would only get the internet when government decided to open it up, and not any time before,” explained Kuda Hove, who is a legal officer with the Zimbabwe chapter of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA-Zimbabwe).

As people tried to figure out what was going on, many switched to the national broadcasting television channel to get a sense of what had happened, how, and when. The Deputy Minister of Information, Publicity and Broadcasting, Energy Mutodi, denied the internet shutdown outright, and instead blamed the inaccessibility on congestion. This was refuted by one of the major internet service providers – Econet – when they sent a message to their subscribers stating that internet services were suspended across all networks following a warrant issued by the Minister of State in the President’s Office.

Even with his strong sense of the lay of the land and the advocacy work MISA-Zimbabwe is involved in, Hove says they did not anticipate a full shutdown of the internet. “There were no prior indications that the government would completely shut down the internet. What we anticipated was a throttling of internet services during the stayaway protests.”

Not only was the shutdown unexpected, it was in contravention of provisions of UN Resolution A/HRC/32/L.20, which condemns online restrictions on freedom of expression and internet shutdowns and generally ensures that the rights people enjoy offline, are protected online.

The internet is so firmly embedded in the day to day lives of most Zimbabweans now, the protection and promotion of internet freedoms are more essential than ever.

The shutdown drew the attention of the outside world. A joint letter, coordinated by Access Now and signed by 28 organisations, implored the government to “keep the internet on”, noting that such shutdowns “harm human rights and economies” and violate international law. The letter also pointed out that “internet shutdowns and violence go hand in hand. Shutdowns disrupt the free flow of information and create a cover of darkness that shields human rights abuses from public scrutiny. Journalists and media workers cannot contact sources, gather information, or file stories without digital communications tools.”

In recent days I spoke to a few Zimbabweans to hear their stories of how the shutdown manifested in their lives. I’ve shared some of their reflections here.

“I was out of the country when Zimbabwe went dark. In fact that’s exactly how I felt – a darkness had descended. Initially I didn’t know what was happening. I was trying to contact my mum – who is not in the best of health – and couldn’t get through. My first thought was that something had happened to her and that’s why she wasn’t responding to my calls and messages. You can imagine the panic that swept through me. I tried to get hold of other family members and couldn’t get through to any of them either. It wasn’t until my brother called from South Africa the next day that I knew what was going on. It was one of the most traumatic experiences I’ve ever had. It honestly felt as if my family had dropped off the face of the earth. Easily one of the worst 12 hours of my life.”

“The shutdown didn’t really come as a surprise. Earlier in the day, there was talk about the shutting down of the internet so I had already logged on to VPN – which, by the way, uses double the amount of data. You can imagine how expensive that is, especially in this country. For me, personally, the internet shutdown meant I couldn’t get vital blood test results from neighbouring South Africa. They eventually came a week later, by which time I’d been treated for the wrong condition. It also meant my doctor couldn’t access my results in real time either. They are usually emailed by the local laboratory to the doctor. This meant I had to drive into city centre and collect my results. I was not sure if it was safe to go to the laboratory as many roads had been blocked by rocks and metal posts and barbed wire and cars were being. During all this I felt like death warmed up! I’m just thankful that my case was not urgent or life threatening. This may have been the situation others were in. It was a very frustrating and uncertain time…. I was particularly concerned about my kids at school and relatives overseas, as it was not possible to be in touch and reassure them that despite everything my family and I were safe.”

“Someone I used to work with quite closely was ill. I used to go see her in hospital. The message about her passing away was shared on WhatsApp, but of course we had no internet, so I only got it after the net was back up. So I didn’t get to go to the funeral, partly because I heard late, and also because of the chaos after the protests. I didn’t get to have a choice about what to do when I heard. The person who told me used WhatsApp, because they’re in another country (easiest way to communicate, and they didn’t know about the shutdown). I am glad I saw her in hospital though. I made my peace.”

A young Zimbabwean citizen-journalist also shared his reflections, on Facebook:

https://www.facebook.com/openparlyzw/videos/351042805729641

As a media advocacy organisation working on access to information, freedom of expression and media freedom issues, MISA-Zimbabwe needs to communicate and interact with their audience of about 31,000 followers across Twitter and Facebook, on a daily basis.

To get around the blackout, programme staff members sent texts to a colleague outside the country, asking them to post messages onto MISA-Zimbabwe’s Twitter and Facebook accounts. “It helped us keep the rest of the world informed.”

They used voice calls and text messages (SMS) to communicate with colleagues locally, as well as with their partners inside and outside of Zimbabwe – an expensive option in a declining economy.

During the partial shutdown, MISA-Zimbabwe also opened up its phone Hotline to questions from Zimbabweans on how to install and use Virtual Privacy Apps such as TunnelBear and Psiphon, which reported tens of thousands of new downloads. However, with the total shutdown, even VPNs became difficult to access.

Hove describes the shutting of the internet as a “desperate effort on government’s part, and a gross overreaction that will adversely affect the government’s standing in the eyes of the international community. Past experience shows that dictatorships and not democratic countries are more likely to shut down the Internet.”

Nevertheless, Zimbabweans’ immense capacity to focus on the lighter side of life and their keen sense of humour was immediately evident through the twitter thread #whiletheinternetwasoff, set up soon after the internet was unblocked.

#WhileTheInternetWasOff I discovered that Zimbabweans are creative. pic.twitter.com/4fxK954Liy

— NewsHubzw (@Trevorsagota) January 22, 2019

The entrepreneurial and the philosophical also came shining through.

#WhileTheInternetWasOff I made a few bucks by installing VPNs for those that didnt know how to get back online.

— Death_by_Sarcasm ???????? (@EutyNcube) January 21, 2019

I learnt how to read actual books not twitter threads ????#WhileTheInternetWasOff

— bitlyon ???????????????????????? (@blacnsilva) January 22, 2019