The latest report from Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) looks at the correlation between the level of authoritarianism in a country, the reluctance of that country's leader to relinquish power and the likelihood of an internet disruption or internet shutdown.

This statement was originally published on cipesa.org on 18 March 2019.

Up to 22 African governments have ordered network disruptions in the last four years and since the start of 2019, six African countries – Algeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DR Congo), Chad, Gabon, Sudan and Zimbabwe – have experienced internet shutdowns.

A new report by the Collaboration on International ICT Policy for East and Southern Africa (CIPESA) titled Despots and Disruptions: Five Dimensions of Internet Shutdowns in Africa notes, however, that internet shutdowns remain the preserve of Africa’s most despotic states.

According to the report, 77% of the countries where internet shutdowns have been ordered in the last five years are categorised as authoritarian under the Democracy Index produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit. All the other African countries that have disrupted communications are categorised as hybrid regimes, meaning they have some elements of democracy with strong doses of authoritarianism.

The authoritarian regimes that have ordered network disruptions include Algeria, Burundi, the Central African Republic (CAR), Cameroon, Chad, DR Congo, Congo (Brazzaville), Egypt, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Ethiopia, Libya, Mauritania, Niger, Togo, Sudan, and Zimbabwe. Hybrid regimes that have ordered internet shutdowns include the Gambia, Mali, Morocco, Sierra Leone, and Uganda.

For countries that are classified as authoritarian but have not ordered shutdowns, the report states that it is likely that “the authoritarian state is so brutal or commanding that civil society or opposition organising and protests – online and offline – are unfathomable” or “internet control measures in place render ordering overt internet disruptions unnecessary.” These countries include Djibouti, Eritrea and Rwanda.

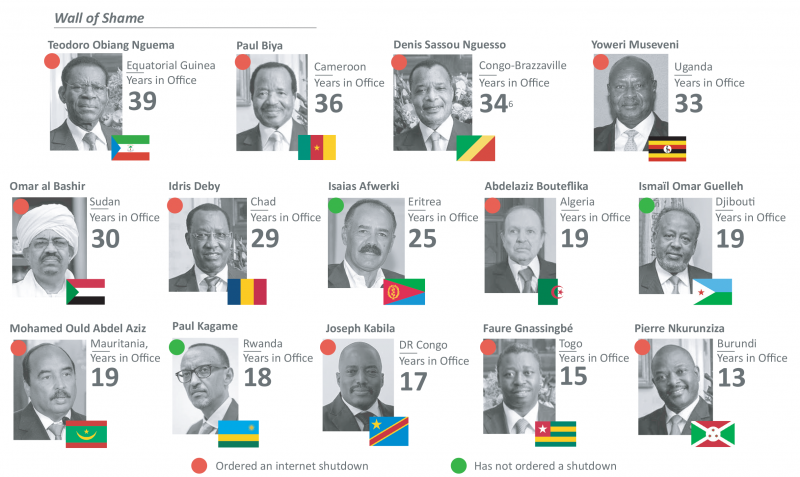

The report also notes that countries whose leaders have been in power for several years are more likely to order internet shutdowns. As of January 2019, of the 14 African leaders who had been in power for 13 years or more, 79% had ordered shutdowns, mostly during election periods and public protests against government policies.

These included Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema (39 years); Cameroon’s Paul Biya (36); Congo Brazaville’s Denis Sassou Nguesso (34); Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni (33); Sudan’s Omar El Bashir (30); Chad’s Edris Deby (29); Algeria’s Abdelaziz Bouteflika (19); Mauritania’s Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz (19); DR Congo’s Joseph Kabila (17); Togo’s Faure Gnassingbé (15); and Burundi’s Pierrie Nkurunziza (13).

The report says 2019 could see a record number of network disruptions since at least 20 African states will hold various forms of elections including local, legislative, general or presidential.

Over the years, many network disruptions have typically occurred in autocratic African countries around election times, and among the states scheduled to conduct polls this year are those which have previously initiated various forms of shutdowns during elections periods (such as Equatorial Guinea), public protests (Cameroon, Togo), and national school exams (Algeria, Ethiopia).

Other highlights from the Despots and Disruptions: Five Dimensions of Internet Shutdowns in Africa report:

The report notes that governments that order disruptions and the Internet Service Providers (ISPs) that implement them now more openly acknowledged the disruptions. Governments often cite digital technologies’ increasing usage to spread disinformation, propagate hate speech, and to allegedly fan public disorder and undermine national security.

For their part, more ISPs and platform operators are making public their responses to shutdown directives as and to user information and interception requests from governments through transparency reports. This openness could represent the normalisation of shutdowns, implying that a growing number of governments feel no shame in openly acknowledging ordering shutdowns. However, it has positive elements too, as it can be the basis of litigation and push back advocacy.

The report reiterates that internet disruptions, however short-lived, affect many facets of the national economy and tend to persist far beyond the days on which access is disrupted. “If just five of the countries that have previously disrupted internet access and who are going to the polls this year disrupted access to internet including apps such as Twitter, Facebook and Whatsapp at a nationwide level for five days each, the estimated economic cost would be more than USD 65.6 million,” the report states.

Further, the report notes that the countries that disrupt internet access have some of the lowest internet usage figures and highest data prices in Africa. Conventional wisdom might suggest that low-internet usage countries would be the last to disrupt internet access as they might consider the population online too small to threaten “public order” or “national security” or to threaten the regime’s hold on power. On the contrary, says the report, it appears that African governments with democracy deficits, regardless of the numbers of their citizens that use the internet, fear the power of the internet in enabling citizen organising and empowering ordinary people to speak truth to power.

The report can be downloaded here.