(SEAPA/IFEX) – The following is an 18 August 2004 SEAPA report: SEAPA backgrounder on “culture of impunity” surrounding deaths of Filipino journalists A rash of attacks on Filipino journalists in the last three weeks underscores the most glaring threat to free and independent journalism in the Philippines. While the country’s press remains one of the […]

(SEAPA/IFEX) – The following is an 18 August 2004 SEAPA report:

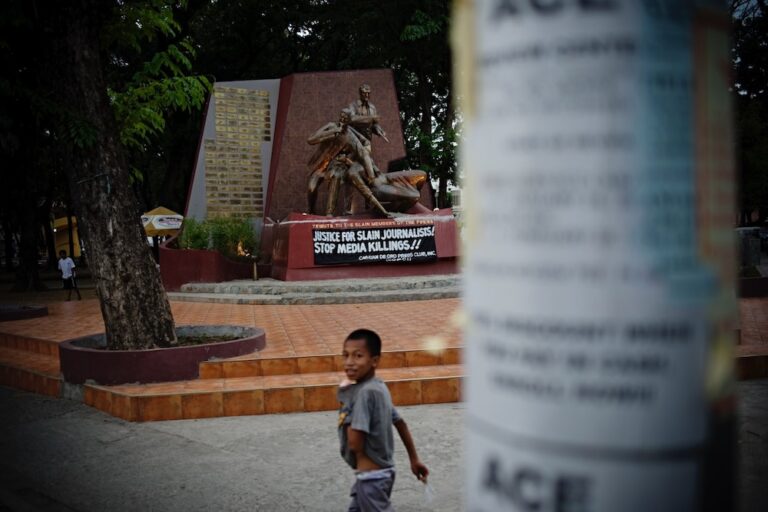

SEAPA backgrounder on “culture of impunity” surrounding deaths of Filipino journalists

A rash of attacks on Filipino journalists in the last three weeks underscores the most glaring threat to free and independent journalism in the Philippines. While the country’s press remains one of the freest and most vibrant communities of journalists in Southeast Asia, its members – particularly those outside Metro Manila and other major urban centers – have been targets of violence for years, and there appears to be nothing being put forward to change this trend.

The apparent murder of Fernando Consignado, a correspondent of Radio Veritas based in Laguna, south of Manila, last Wednesday represented the fourth murder of a Filipino journalist in two weeks – the fifth since January and the 54th since 1986. “Only Iraq has seen more journalists killed so far this year,” the Committee to Protect Journalists notes.

On the one hand, the journalists are clearly being targeted by various parties and interests – from drug and gambling lords in their provinces to officials and public figures they accuse of graft and corruption. But what truly leaves them vulnerable, Filipino journalists and human rights advocates say, is the “culture of impunity” that government – the Philippine police and legal systems, in particular – has been allowing to fester for two decades now.

By “impunity”, they refer to one unfortunate fact: No single suspect has been convicted or jailed for any of the 54 cases of journalist murders in the Philippines since the 1980s. (CPJ research confirms that at least 44 of those 54 attacks were directly related to the slain journalists’ work.) There appears to be no serious effort on the part of government to protect journalists and the press in general – and in this regard to give recognition to, and discourage attacks on, a pillar of Philippine democracy.

The current police chief of the Philippines, Hermogenes Ebdane, Jr., has proposed relaxing gun laws to allow journalists to arm themselves. Meanwhile, the leader of the Philippine House of Representatives, Speaker Jose De Venecia, has promised to raise a P2 million reward for information leading to the capture of Consignado’s killers.

Philippine free press advocates have rejected both initiatives, and have decried them as missing the point to recent protests carried out by Filipino journalists. If anything, the reactions of the police and the nation’s political leaders further illustrate how they have abdicated their duties and responsibilities towards empowering the press and ensuring that Filipino journalists are free to do their job well and without fear of reprisal.

Meanwhile, independent investigations by Philippine press advocates continue, alongside and in coordination with investigations of international groups such as the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Inday Espina-Varona, chairperson of the National Union of Journalists in the Philippines (NUJP), says: “The Philippine government likes to boast of a freewheeling democracy. A succession of Malacañang occupants have claimed that media in this country is, and has always been, an ally in the preservation of democracy. And yet, as events of 2003 and the past months show, the Philippine Press is under siege by a society that increasingly shoots or arrests its messengers.” The attacks on journalists affects Philippine society in general, she adds. “When media is oppressed, when it is literally under fire, it is society itself that is besieged.”

To be sure, the Philippine media faces other problems.

Outside of outright killings, Varona notes, “there have been many arrests of journalists in the past few years. Libel cases are being filed in record numbers. Soldiers have surrounded journalists during fact-finding missions, and military officers remain wont to accuse reporters of involvement in rebellion. Troops and local government units have also closed down several radio stations. There have been government gag orders and threats to file criminal suits against media entities that do not toe the official line. We have experienced public harangues, news blackouts, outright disinformation, denial of access to information, prior restraint on coverage – as well as self-censorship.”

But it is the “impunity” with which different interests are murdering Filipino journalists that most betray the Philippine government’s apathy towards the weakening of the media, press advocates say.

“As the freest media country in ASEAN, the Philippine government must render sufficient political will and resources to bring to justice those murderers,” said Kavi Chongkittavorn, chairman of the Bangkok-based Southeast Asian Press Alliance. “Otherwise, the impunity there can become wide-spread as ASEAN countries normally do not have sympathy towards the media.”

“The culture of impunity in the Philippines must be stopped,” CPJ Executive Director Ann Cooper said. “We call on authorities to carry out a swift and thorough investigation [into Consignado’s murder and] the other deadly attacks on journalists, and to prosecute those responsible for all of these murders. Police should not abdicate their responsibility to uphold the law and safeguard press freedom.”