“If you criminalise news gathering, you are criminalising journalism. It is a moral duty for journalists to protect sources. Many have gone to jail to protect that principle.”

This statement was originally published on ifj.org on 10 September 2020.

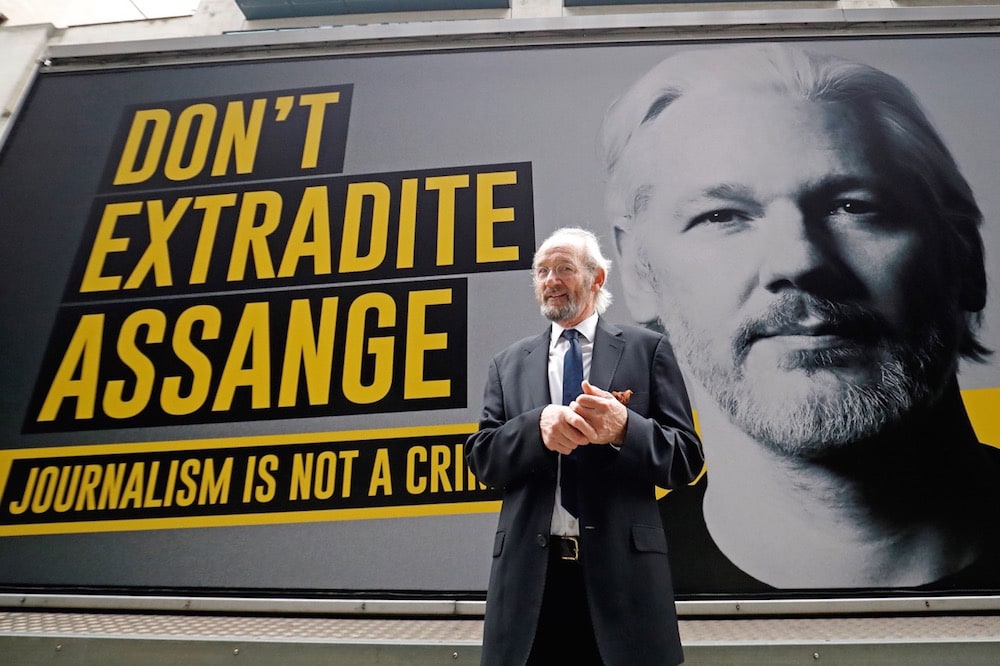

“If you criminalise news gathering, you are criminalising journalism. It is a moral duty for journalists to protect sources. Many have gone to jail to protect that principle.” Follow Julian Assange’s hearing in London with IFJ Representative Tim Dawson.

It took some time to warm up, but the courtroom duel between James Lewis QC and Professor Mark Feldstein of Maryland University laid bare some fundamental issues for journalists. Both were appearing at the Old Bailey, London: Lewis making the case for the US government that Julian Assange should be extradited; Feldstein, called as an expert witness to explain how journalists work.

Lewis has been at the bar for more than 30 years, and promotes his services with the strapline: “a charming man with a mega brain”.

By way of trying to demolish the testimony and reputation of his opponent, he deployed a classic barrister’s technique. He asked a series of apparently simple questions that led the witness into a trap from which there is no escape without undermining their own evidence. Or at least, that was clearly his hope.

Lewis: “Is it your view Professor, that journalists are above the law”.

Feldstein: “No, sir, it is not”.

Lewis: “And is it your view that a journalist should be allowed to hack someone’s computer to unearth private matters, or burgle their home?”

Feldstein: “No it is not my view”.

Lewis: “So if a journalist helps someone to burgle a home or hack a computer to obtain information, can we agree that they have clearly broken the law?”

Feldstein, after a pause: “It depends on the details, that is where it gets a bit squishy.”

Whether that was quite the denouement Lewis hoped for was unclear, but from Feldstein’s earlier evidence, it was clear how fundamental this point is to reporting. Feldstein described how, during his own distinguished career as a journalist he had frequently been in receipt of leaked material. He said that helping a source to remove material undetected and disguising their part in doing so was ‘standard operating procedure for journalists’ and something he taught his own journalism students.

A moment or two later, the advocate tried a similar manoeuvre.

Lewis: “Will you agree with me Professor, that there are some secrets that a state is entitled to keep? – troop movements in time or war and the nuclear codes, for example?”

Feldstein: “Of course”.

Lewis: “So if someone tries to steal details of troop movements during war, or the nuclear codes, or material that could put people at risk, if is reasonable to consider that a crime”.

The video link over which Feldstein was speaking left this point slightly lost – although Lewis’ rhetorical sleight of hand was clear. The first two instances are unequivocal cases, the third a significantly more conjectural catch all.

Feldstein came back strongly. “If you criminalise news gathering, you are criminalising journalism. It is a moral duty for journalists to protect sources. Many have gone to jail to protect that principle.” The professor went on to say that he thought the US government could, with this case, be trying to create precedents that would allow it to pursue other members of the news media.

This point is the one on which this entire case hangs. The acts for which extradition and prosecution are sought are clearly ones that might have been committed by any investigative journalist. Whether or not you consider Assange to be a journalist, or indeed, if his unredacted publication of leaks was ‘responsible’, are peripheral issues.

Other evidence from Feldstein highlighted what a risk this might be, given the frequency of US administrations considered prosecuting leak-receiving journalists. Richard Nixon hoped to silence Jack Adamson (even considering having him killed), for example and Obama desperately searched for means to get Assange into court.

The previous witness, distinguished human rights lawyer Clive Stafford Smith, clearly illustrated what might be lost if obtaining leaks were criminalised. He described a US system of government that had, since 9/11, sought to classify almost every piece of information in its possession.

His example of how absurd this could be was fascinating. “When I first went to see a British man in Guantanamo Bay he gave me 30 pages on the torture that he had suffered. All of this material was immediately classified on the basis that revealing torture was a threat to (US) national security”.

Stafford Smith argued that the ‘US obsession’ with secrecy post 9/11 meant that much that was classified was simply material that was embarrassing, or provided evidence of bad decision making.

The clear implication was that if being in receipt of classified material without authorisation was criminalised, there would be little to report in the future.

Stafford Smith also vividly illustrated the broader importance of journalism. Revelations from Wikileaks helped end a US assignation programme that had targeted journalists among others, he said. They also provided the basis for ending drone strikes in Pakistan. And he had personally used material leaked by Assange to secure the release of innocents incarcerated in Guantanamo Bay.

The challenge for Assange’s legal team over the three weeks scheduled for the hearing, is to persuade both the judge, and the public more generally, of this case. The witness list looks encouraging. Pentagon Papers leaker Daniel Ellsberg is cited, as is distinguished journalist Patrick Cockburn and Noam Chomsky.

Whether they will be sufficient to persuade the judge, Vanessa Baraitser, remains to be seen. Few decisions to date have gone with the defence. They asked for Assange to sit with them in court, rather than in the bullet-proof dock, and were refused. They sought to have the fresh charges levelled over the summer struck out, and found her unsympathetic. And their request for a three month adjournment to prepare to answer the new charges was also denied.

What is in no doubt, however, is that if Assange is extradited, he will face charges that could result in 175 years in prison. These would be served in solitary confinement and with little access to family, friends or lawyers.

Notwithstanding the personal effect on Assange of such an outcome, this would surely give journalists real pause for thought if they are ever offered classified US information in the future.

The hearing continues.

Tim Dawson