Wealthy individuals, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, are abusing the law to stifle critical reporting. However, journalists are fighting back.

This statement was originally published on freedomhouse.org on 19 October 2023.

Wealthy and powerful individuals, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, are misusing the law to stifle reporting on their activities. But journalists are fighting back to protect the principles of openness, accountability, and transparency.

To say that independent journalism is necessary is an understatement. Without the painstaking efforts of journalists, the world’s news consumers might not have learned about the reach of spyware, the use and misuse of funds earmarked to fight COVID-19, or how politicians worldwide employed offshore tax havens. But wealthy and powerful individuals are increasingly using the law to evade that scrutiny by filing strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) – meritless suits that entangle, exhaust, and ultimately silence media outlets, individual journalists, civil society groups, and activists.

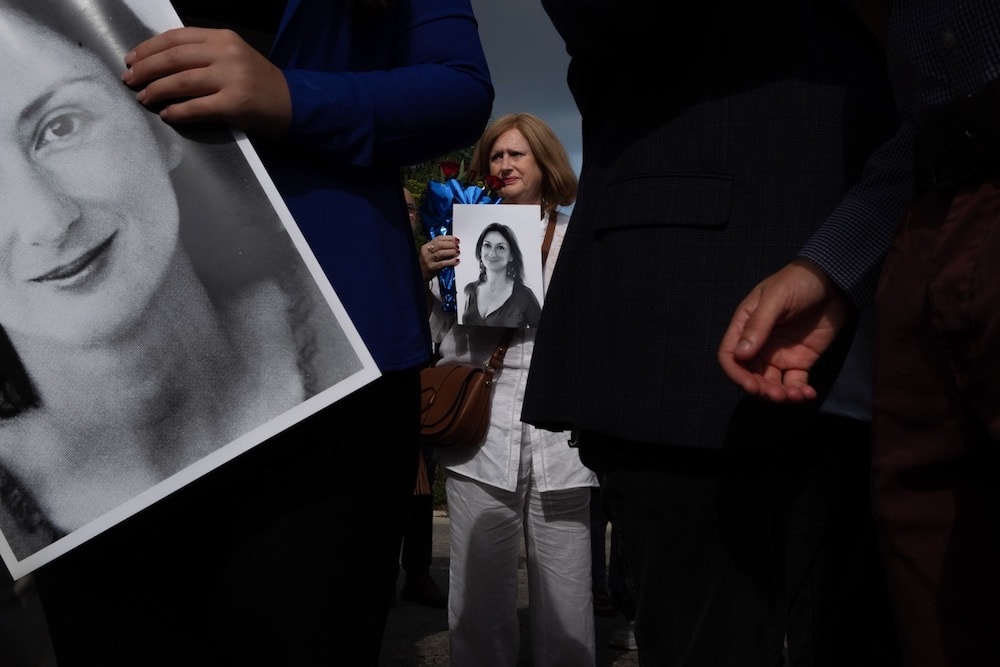

This phenomenon is not limited to one corner of the world. SLAPPs have done enough harm that more than half of US states have legislated to arrest the practice. Only three months ago, a group of Latin American journalists testified on how SLAPPs have impacted their lives and threatened their finances. And even though the case of Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia – who faced scores of libel suits before she was murdered in 2017 – demonstrated how harmful SLAPPs can be, these cases are becoming more common in European courtrooms. They are especially impactful in Central and Eastern European nations, where rule of law is relatively weak, media outlets are poorly resourced, and corruption is pervasive.

The region’s citizens have suffered the consequences as newsrooms retreat and self-censor under this onslaught. But journalists are fighting back for the sake of their profession and for the fundamental right to know.

Abuse, not justice, in the courtroom

Plaintiffs who file SLAPPs stand a better chance of success in countries where judicial systems are neither evenhanded nor independent. In Poland, outlets like Gazeta Wyborcza and OKO.press have faced a litany of SLAPPs filed by officials, state-owned companies, and individuals close to the Law and Justice (PiS) party. Gazeta Wyborcza alone has faced over 90 lawsuits and legal threats since 2015. PiS has done much to curb the judicial branch and install friendly judges since taking power that year, with corrosive results for investigative and critical journalism in Poland. “It’s like a domino effect… The impact on us is that we start losing cases, which are obvious cases that we should win if judges were really independent,” explained Piotr Stasiński, a longtime editor at Gazeta Wyborcza, in a recent interview with Freedom House.

In Bulgaria, where judges have also displayed a progovernment bias on the bench, journalists are similarly right to be wary. In late 2021, for example, two reporters from the Mediapool news site were convicted of defamation at a Sofia court that was once headed by the plaintiff. Bulgarian prosecutors have been known to meddle in SLAPP cases, too; when the Bureau of Investigative Reporting and Data published an article detailing the apparent links between law enforcement and organized criminal groups earlier this year, Prosecutor General Ivan Geshev accused the outlet of engaging in a conspiracy.

Little to gain, much to lose

SLAPPs also represent a significant financial burden for defendants. Plaintiffs unabashedly intimidate and cripple their victims by exhausting their bank accounts just as much as their time and energy. In countries where state resources—notably public advertising—are additionally tied to favorable coverage, outlets drop certain stories to avoid the legal and financial consequences.

The bill can be high, disastrously so for strapped local outlets. In 2018, RISE Project, a Romanian investigative outfit, was threatened with a €20-million ($23.4-million) fine for allegedly violating the General Data Protection Regulation of the European Union (EU), after it shared corruption allegations that involved the ruling party’s head on Facebook. Although RISE Project suspected that the threat was politically motivated, it still took down the post. In 2022, Croatian journalist Davorka Blažević was successfully sued for eight times her salary by a Supreme Court judge for “insult of honor and reputation.” The offending article was a “portrait of the week” published in 2015 by a nonprofit outfit based in a small city.

The fightback begins

As SLAPPs have imperiled journalists and outlets, civil society has called for reform to protect the press. In a promising first step, the European Commission proposed an anti-SLAPP directive (often called Daphne’s Law) that remains under consideration. However, the proposed directive’s reach is limited to cross-border cases and civil litigation. On top of this, EU member states have weakened key provisions that would foster early dismissals and provide compensation for defendants, further limiting its potential effectiveness.

As EU countries and institutions continue to negotiate over the fate of the directive, journalists in Central and Eastern Europe are devising new ways to protect themselves and each other. As Freedom House’s special report, Reviving News Media in an Embattled Europe, has highlighted, outlets in the region are mounting defenses against SLAPPs through support networks, cross-border collaboration, and legal defense funds. Crowdfunding campaigns have proven to be a lifeline for journalists in Bulgaria and Croatia, while Romanian journalists are launching legal appeals that could level the domestic playing field.

But media cannot turn the tide on their own. Regional donors can financially bolster defendants in their fight against SLAPPs, while political leaders can build their own early-dismissal mechanisms. But above all, judiciaries in Central and Eastern Europe must be depoliticized and the rule of law must be strengthened so that courtrooms can serve as a bulwark for independent media. Otherwise, governments risk more than an embarrassing news story: They risk journalism that says nothing at all.