Human Rights Watch said that the Vietnamese government should end its crackdown against bloggers, rights campaigners, and activists.

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 5 March 2024.

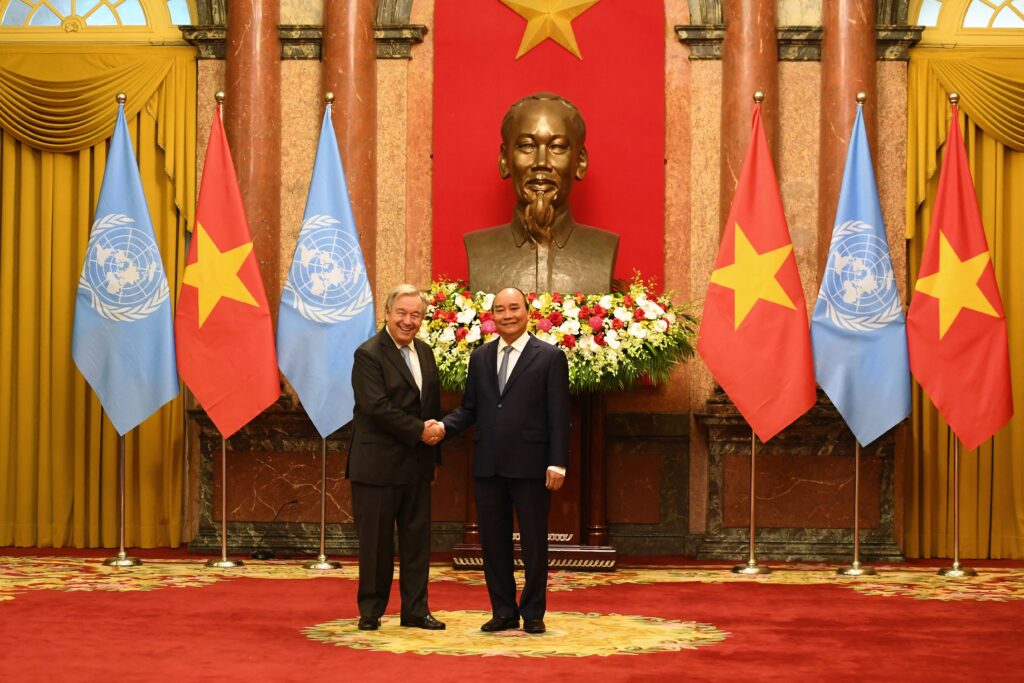

Repression spikes amid bid for another UN Human Rights Council term

The Vietnamese authorities arrested three prominent critics just days after Vietnam announced its candidacy for another term on the United Nations Human Rights Council, Human Rights Watch said today. The police arrested Nguyen Chi Tuyen and Nguyen Vu Binh on February 29, 2024, and Hoang Viet Khanh on March 1, and charged them with conducting propaganda against the state.

The Vietnamese government should end its crackdown against bloggers, rights campaigners, and activists, and immediately release those held for exercising their basic civil and political rights. In 2022, the UN General Assembly elected Vietnam to a three-year term on the Human Rights Council in Geneva, which ends in 2025. It announced on February 26 that it will seek a new term when its term ends.

“The Vietnamese government likes to boast about its respect for human rights when seeking a seat on the UN Human Rights Council, but its brutal crushing of dissent sends the opposite message,” said Phil Robertson, deputy Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “Despite Vietnam’s egregious treatment of rights advocates, the country’s donors and trade partners have done almost nothing to press the government about its rights abuses.”

Vietnam currently holds at least 163 political prisoners, Human Rights Watch said. During the first two months of 2024 alone, three activists – Danh Minh Quang, Nay Y Blang, and Phan Van Loc – were convicted and sentenced to between three years and six months, and seven years in prison. At least 24 other persons are in police custody on politically motivated charges awaiting trials.

The police arrested Nguyen Chi Tuyen (also known as Anh Chi), 49, on February 29 in Hanoi. He is a rights campaigner who uses social media, including YouTube and Facebook, to comment on social and political issues. His primary YouTube channel, Anh Chi Rau Den, has produced over 1,600 videos and is followed by 98,000 subscribers. His second YouTube channel, AC Media, has produced more than 1,000 videos and has almost 60,000 subscribers.

Nguyen Chi Tuyen was a founding member of the now closed No-U FC (No U-line Football Club), a soccer team whose members were outspoken against China’s territorial claims on maritime areas claimed by Vietnam. He helped organize and participated in many anti-China protests in the early 2010s, and pro-environmental protests in the mid-2010s. He joined fellow activists to provide humanitarian assistance to impoverished people in rural areas and victims of natural disasters.

He also openly supported imprisoned rights activists including Pham Doan Trang, Can Thi Theu, Nguyen Tuong Thuy, Nguyen Huu Vinh (Ba Sam), and Nguyen Lan Thang. Prior to Nguyen Lan Thang’s trial, Nguyen Chi Tuyen published an open letter in support of his friend. He wrote, “The only thing we did was to act in accordance with our conscience, speak up our thoughts, our desire, our longing.”

Nguyen Chi Tuyen has repeatedly faced police intimidation, harassment, house arrest, bans on international travel, arbitrary detention, and interrogations. In May 2015, five unidentified men attacked and beat him near his house in Hanoi. The attack left him with injuries that required stitches in his face. In February 2017, Nguyen Chi Tuyen and five fellow activists met a European Union human rights delegation in Hanoi to discuss the human rights situation in Vietnam. Of the six Vietnamese activists present that day, Pham Doan Trang and Nguyen Tuong Thuy are now serving long prison sentences. Two others, Vu Quoc Ngu and Nguyen Anh Tuan, fled the country to escape likely arrest.

Despite the risk of prosecution on politically motivated charges, Nguyen Chi Tuyen continued his campaign for human rights and democracy. In a 2017 interview on Mekong Review, he said, “[The Communist Party] have all the power in their hands. They have prisons, they have guns, policemen, army force, the court: they have everything. They have media. We have nothing except our hearts, and our minds. And we think it’s the right thing to do… that’s all.”

On February 29, the police also arrested Nguyen Vu Binh, 55, a former political prisoner, in Hanoi. After working as a journalist at the official Communist Party of Vietnam’s journal, Communist Review (Tap Chi Cong San), for almost 10 years, in December 2000 he resigned and attempted to form an independent political party. He was also one of several dissidents who attempted to form an anti-corruption association in 2001. Police arrested him in September 2002, alleging that he slandered the Vietnamese state in written testimony he provided to the US Congress in July 2002 regarding human rights abuses in Vietnam. The government also targeted him for his criticism of a controversial border treaty with China in an article distributed online in August 2002.

In his testimony, Nguyen Vu Binh wrote, “I always believe that when we can successfully stop and prevent human rights violations across the country we have also succeeded in democratizing this nation. Any measures to fight for human rights, therefore, should also aim for the ultimate goals aspired for so long by the Vietnamese people: individual liberty and a democratic society.”

In December 2003, a court sentenced Nguyen Vu Binh to seven years in prison, followed by three years of house arrest, for espionage under article 80 of Vietnam’s Criminal Law. In June 2007, the authorities pardoned and released him two years and three months early. He immediately resumed his advocacy for freedom, democracy, and human rights. He frequently commented on various social and political issues of Vietnam.

Between 2015 and 2024, Nguyen Vu Binh has published more than 300 entries on the Radio Free Asia Blog. In his latest entry, “Positive Aspects of the Democratic Movement During a Difficult and Gloomy Period,” published a week before his arrest, he said that human rights and democracy advocates in Vietnam support one another, and the families of fellow activists, amid the ongoing government crackdown.

Nguyen Vu Binh twice received the prestigious Hellmann/Hammett writers’ award for writers who have been victims of political persecution, in 2002, and 2007.

On March 1, police arrested Hoang Viet Khanh, 41, in Lam Dong province, in the Central Highlands region. He started using Facebook to express his opinions on various socio-political issues in Vietnam in 2018. He denounced police brutality and raised concerns about confessions extracted under torture in police custody. He publicly voiced support for political prisoners including Pham Chi Dung, Nguyen Tuong Thuy, Le Huu Minh Tuan, Le Chi Thanh, Le Trong Hung, and Le Van Dung.

Commenting on the trial of a citizen journalist, Le Van Dung, Hoang Viet Khanh said that by arresting people who use Facebook to express their opinions, the government aims to intimidate citizens so they would be “afraid to expose the truth unfavorable to the one-party regime.” He added that the ultimate goal of arrests of dissidents is “to intimidate and prevent citizens from exercising freedom of speech.”

When Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh first took office in 2021, Hoang Viet Khanh published his 10-point opinion, urging the prime minister to consider abolishing article 4 of Vietnam’s Constitution, which confirms the Communist Party’s leadership over the country.

The police accused him of using his Facebook page to “post, share and disseminate [information with] contents that bend the truth, distort and twist the actual situation, attack the guidelines and policies of the party and the state, distort history, defame and insult President Ho Chi Minh, [and] smear high-ranking leaders of the party and the state.”

“These three activists are not guilty of anything except exercising their basic rights to freedom of speech,” Robertson said. “Unfortunately, the Vietnamese government treats all online expression of peaceful political views as a dire threat to the ruling party and government, and crushes such dissent with politically motivated arrests, trials, and prison sentences.”