"We are tired and exhausted, and we have done everything in our power to tell the story."

This statement was originally published on cpj.org on 23 May 2024.

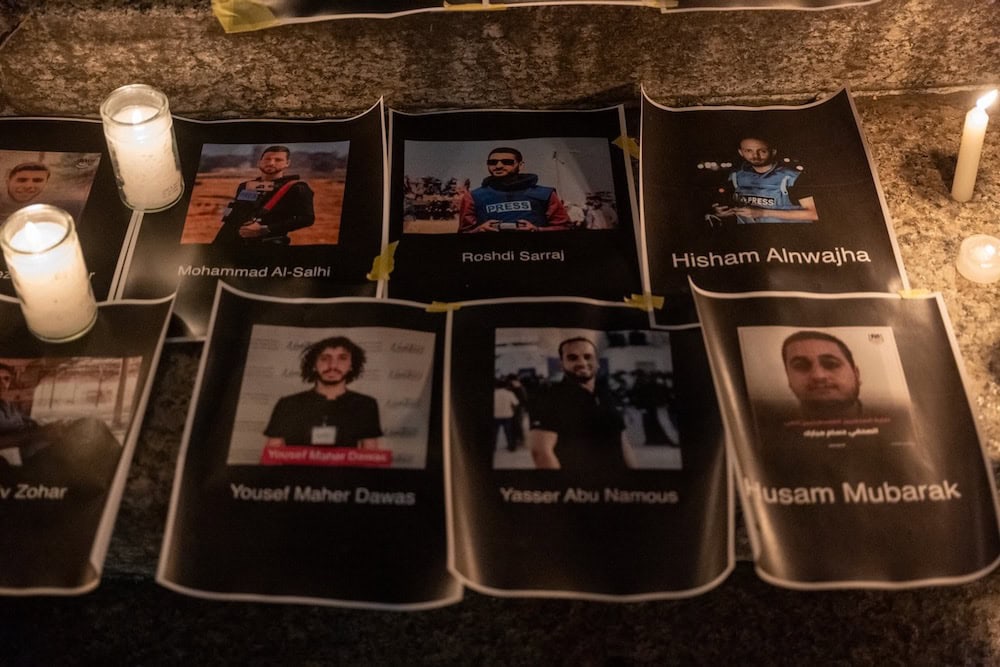

Gaza journalists Shrouq Al Aila and Roshdi Sarraj were on a work trip in Saudi Arabia last fall when their home became a war zone. The married couple quickly returned to Gaza to report and to be with their community. But Sarraj, the founder of local production company Ain Media, would only manage to produce a few reports. On October 22, he was killed in an Israeli airstrike.

Al Aila, 29, quickly picked up where her husband left off and became the head of Ain Media covering the war and displacement of Gaza’s residents. The production company has suffered other losses; early in the war photographer Ibrahim Lafi was killed and Haitham Abdelwahid, also a photographer, went missing along with a close journalist friend, Nidal Al-Wahidi. Sarraj’s founding partner at Ain Media, Yaser Murtaja, was murdered by an Israeli sniper in 2018.

Al Aila spoke to CPJ from Rafah, in southern Gaza, where she was sheltering with her young daughter. Since the interview she moved to a tent in Deir al-Balah to escape Israel’s expanded offensive in Rafah, the family’s third displacement since the war began. The interview was conducted using WhatsApp voice notes; every time she paused in her narration, the sound of Israeli drones, what Gazans call the “zanana” (buzzing sound), was audible on the recordings.

The interview was lightly edited for length and clarity.

Can you describe the day your husband was killed?

It was a Sunday. We sat down to have breakfast at 11:00 a.m. Roshdi had an assignment to film the paramedics and their first aid operations. I told him that I was worried about this assignment, and that I didn’t want him to ride in the ambulance to film, because they were hitting the ambulances. He said, “Who will film if I don’t? Someone should deliver the message.”

Roshdi was rushing his family to have breakfast that morning. His mom was telling him, “Have your breakfast and go to your assignment — we still have a lot to do before we can eat.” Roshdi is typically calm and chill, but he was agitated. He insisted: “We’ll have breakfast together.” So, we gathered around the table. I was picking up a piece of bread when an airstrike on a nearby building caused a big shockwave and the dining table moved from its place.

The nine of us went into the garden. I was holding Roshdi’s hand in one hand and in the other, I was carrying Dania, our 11-month-old daughter. My sister called, and yelled that Tal al-Hawa, a beach area nearby, was being hit extensively. Our house is in southwest Gaza City, close to the beach. The strikes were many, close, and ongoing.

Roshdi moved and stood in front of me and Dania, still holding my hand. I tried to move him next to me. Suddenly, everything turned gray. The first thing that came to my mind was that my blood sugar was low [and I must have been fainting] but then I started smelling the smell of a strike: the smell of concrete, rubble, and gunpowder.

I couldn’t see anything, but Roshdi wasn’t holding my hand anymore. I started waving my hand, searching, but I couldn’t see or feel Roshdi. At that moment I still didn’t understand that we were actually hit. For us, when you are hit, “khalas” [that’s it], it’s the end, you will die… But I was alive, standing in my place, and Dania and I hadn’t moved, even though the house was hit by two rockets.

When my view began to clear, I saw Roshdi. I touched him and held his hand to try to pull him up, but he fell down again. We carried Roshdi in front of the house. I could see a crack above his right eyebrow. It was about two centimeters [0.8 of an inch], and it was bleeding. I could see his brain convulsing. He was still alive and having difficulty breathing. People next to me were screaming and calling for help. I contained myself and called my brother, who is a doctor, and told him what happened. He said he was coming. The ambulances told us they couldn’t reach us because the whole area was under extensive bombardment. This is the moment when I lost it.

We put him on a soft blanket, carried him, and started walking under the consecutive strikes to the hospital. When we arrived at the hospital, carrying Dania, everyone was calling me. I was reading the Ya-Sin surah of the Quran. Roshdi’s father said “You’re a believer. Roshdi’s injury is critical. Pray for him.” I didn’t understand. I asked him “Did he die?” He answered “No, he is a martyr.” Roshdi needed an emergency operation with doctors who specialize in the brain and nerves. Such doctors weren’t available.

We buried Roshdi in an emergency graveyard. There were about 20 martyrs, and they wanted to bury him in one mass grave with everyone else. Some friends said no, we should separate him, but his father wanted to bury him like everyone else. They ended up just putting a board to separate him from the others. This is our “luxury” and the reality of our graves. He wasn’t buried like we usually honor the dead.

Now, I’m a widow, an orphan [because my parents died in my childhood], and raising an orphan.

After your husband was killed, you stepped in to lead Ain Media. How are you able to work?

Only four of our team members are able to work right now. The circumstances are dire. We are not superheroes, but when I think about our ability to deliver, I say that we are. All of Ain Media now depends on one camera. Can you imagine?

We can’t find equipment, so we tried buying it from people who don’t need it, but some, including journalists, are exploiting the situation and raising the prices. So if a mic costs usually US$400, it’s now US$1,000.

[Before we fled Rafah] we had recently moved to a house with solar panels where I could finally charge my devices myself. Before, we used to send our laptops and phones to a supermarket with solar panels that would charge the devices in exchange for U.S. dollars. It would take about four hours, so for at least four hours a day I was disconnected from the world.

There’s only one bank working but thousands are in line waiting, so you will never get your turn. We resorted to exchange facilities, who would retrieve your money for a 20% cut. Madness.

We now use the toktok [a three-wheel motorbike] and the caro [an animal-drawn carriage], but even finding that kind of transportation is a luxury. Sometimes we travel on foot, which is extremely tiring.

The internet is extremely bad. After the bombardment of transmission towers, the connection became worse. We even tried to connect from the Egyptian side and some people tried connecting from the Israeli side, but it’s very difficult to upload content. This is the most difficult problem for us now. The clients needs their material. Now if you want to upload one gigabyte, it costs four dollars by people with internet who charge others to connect. If I shoot 100 gigabytes of material, which is the size of a documentary we produced for Al Jazeera, it costs US$400 just to upload it.

This is all lost money. You need extra money for equipment, to upload content, for transportation, and to charge your devices. This is the extra cost of media production in the war, and it’s really tiring.

What motivates you to continue amid the hardship?

What I feel for Ain Media is different. It is the place where I met Roshdi. It is the point of intersection and love. I know how much effort and time Roshdi put into it. Most of our conversations even at home were about Ain Media. I would never disappoint Roshdi and leave everything behind. This is what’s pushing me. I don’t know what will happen after the war, but now, Ain Media’s name should always be in the production. No one can comprehend how we’re doing it.