In the first half of 2024, incumbent leaders were more likely to lose elections in countries rated Free than those rated Partly Free, while autocrats went undefeated in largely pro forma elections held in their states.

This statement was originally published on freedomhouse.org on 25 July 2024.

A key principle of democracy is the peaceful transfer of power through the ballot box. While recent elections in France and the United Kingdom saw voters register their desire for change, global trends have been more complicated. In the first half of 2024, incumbent leaders were more likely to lose elections in countries rated Free than those rated Partly Free, while autocrats went undefeated in largely pro forma elections held in their states. Meanwhile, political violence and legal manipulation posed a growing threat to election integrity around the globe.

Voting the rascals out

Incumbent parties maintained power in just half of the 18 national elections held in countries rated Free by Freedom House. In Europe, voters demonstrated a clear desire for change. If the 2010s backlash against austerity policies resulted in greater support for populist leftist movements in countries like Greece, Italy, and Spain, more recent concerns over inflation, immigration, and inequality have arguably benefited a new crop of radical parties on the right.

In France, anti-incumbent sentiments and the collapse of mainstream parties have pushed voters to the fringes. The far-right National Rally (RN) received the most votes in the first round of snap elections, though it ultimately finished third after a new leftist coalition and President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist group unified their supporters against it. In contrast, Prime Minister Keir Starmer achieved a landslide victory in the United Kingdom after he shifted his Labour Party toward the center, putting it in a better position to compete with the Conservative Party, which had moved to the right and lost popularity during a tumultuous 14 years in government.

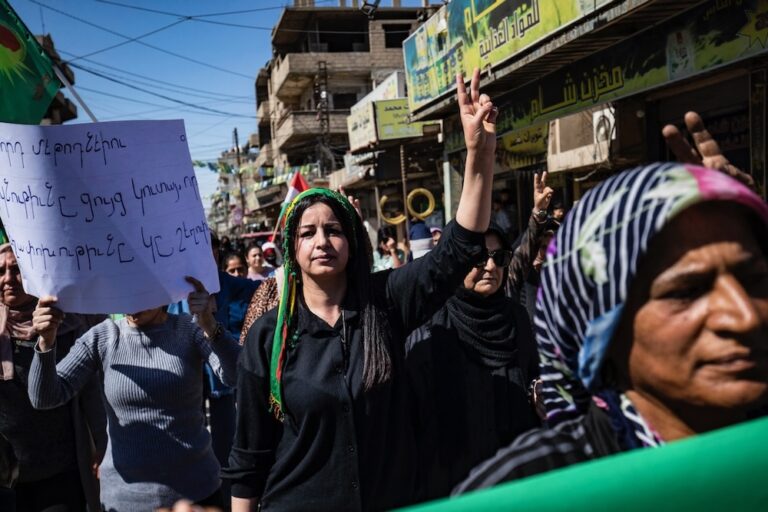

An alarming uptick in political violence and violent rhetoric

Several Free and Partly Free countries saw outbreaks of election-related violence. Some 40 local politicians and activists were killed in the lead-up to South Africa’s general elections this May, in which the African National Congress (ANC) lost its parliamentary majority for the first time since the end of apartheid. South Korean opposition leader Lee Jae-myung was stabbed in the neck before going on to easily defeat President Yoon Suk yeol’s party in April’s legislative elections. In Mexico, criminal gangs murdered a record number of candidates prior to the elections held this June.

Politicians have also vilified minorities and marginalized groups. Prime Minister Narendra Modi smeared India’s 200 million Muslims as “infiltrators” during a campaign speech in this spring’s Lok Sabha elections, in which his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won the most seats but lost its parliamentary majority. In the United States, Donald Trump has denigrated immigrants as “animals” that are “poisoning the blood of our country.” An assassination attempt against the former president on July 13 drew calls for both sides to reduce inflammatory rhetoric ahead of elections in November.

Keeping power at all costs

Election manipulation was a major driver of declining freedom in 2023 and continued into the first half of this year. Incumbent forces retained power in around three-quarters of elections in countries rated Partly Free, a reflection of more election interference by their ruling establishments.

In Indonesia, the Constitutional Court – which is chaired by the outgoing president’s brother-in-law – adjusted age requirements to allow the president’s son to serve as the running mate of Prabowo Subianto. Judicial interference was even clearer in El Salvador: after replacing all of the judges on the constitutional court, Nayib Bukele was able to ignore the country’s single-term limit and coast to victory in February’s presidential election.

While ruling parties were more likely to win in Partly Free countries, they were guaranteed victory in countries rated Not Free. In Rwanda, President Paul Kagame reportedly won 99 percent of the vote after officials banned his opponent from the election and changed constitutional term limits, allowing him to continue his third decade in power. President Vladimir Putin claimed 88 percent of the vote in Russia, where officials arbitrarily disqualified opposition candidate Boris Nadezhdin after his antiwar messaging resonated with disenchanted voters.

A popular autocrat is an oxymoron

The supposed popularity of authoritarian leaders belies the cruel and unjust lengths they have gone to stifle political competition, restrict civil liberties, and undermine the rule of law. In contrast, low approval ratings for democratic leaders should not be mistaken for declining faith in democracy. Recent polling from the Pew Research Center shows that support for representative democracy remains high, even if voters are dissatisfied with the results their democracies are delivering.

As elections in Europe and elsewhere demonstrate, rising anti-incumbent sentiment need not always translate into gains for authoritarian forces. Competent leadership and a united coalition can go a long way toward keeping demagogues at bay. Where far-left and far-right parties have entered government, their worst inclinations have often been curbed by strong institutions and an informed public. Voters remain the strongest check on authoritarian overreach—so long as the power to shape outcomes remains in their hands.