In a landmark judgment on 5 December 2014, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights ruled that Burkina Faso violated the right to freedom of expression of Burkinabé journalist Issa Lohé Konaté.

This statement was originally published on hrw.org on 8 December 2014.

By Leslie Lefkow

Journalists and human rights defenders across Africa achieved a huge victory in the battle for freedom of expression.

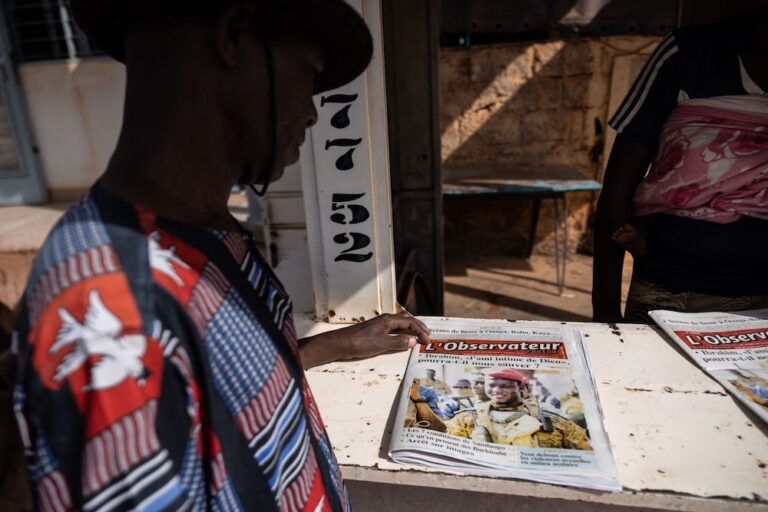

In a landmark judgment on December 5, the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights ruled that Burkina Faso violated the right to freedom of expression of Burkinabé journalist Issa Lohé Konaté. Konaté, the editor of a weekly newspaper, was sentenced to 12 months in prison in 2012 after he published two articles accusing a public prosecutor of abusing his power. His paper was shut down for six months, and he was ordered to pay excessive fines, damages, and costs.

From Angola to Tunisia to Somalia, criminal defamation laws are used by governments to jail journalists like Konaté who try to expose corruption, critique government policy, and inform the public. International norms on freedom of expression standards hold that defamation should be considered a civil matter, not a crime punishable with imprisonment. These norms also recognize that public figures, while entitled to protection of their reputation, should tolerate a greater degree of criticism than private citizens.

Activists have long called for the abolition of criminal defamation laws, arguing they are open to abuse and can result in very harsh consequences. And as repeal of these laws in an increasing number of countries shows, these laws are not necessary for protecting reputations.

The African human rights court’s ruling is sweet vindication for Konaté and his lawyers at the Media Legal Defence Initiative, but its significance extends well beyond Burkina Faso. The court ordered Burkina Faso to amend its law and the African court’s decisions are binding on all African Union member states.

Take Angola, where Rafael Marques de Morais, a leading anti-corruption activist, has been charged with numerous criminal defamation charges. As in many such cases, the human rights violations and corruption alleged by Marques have been ignored, while the Angolan government focuses instead on suppressing his reporting.

Or Swaziland, where the editor of Swaziland’s the Nation newspaper, Bheki Makhubu, and human rights lawyer Thulani Maseko were jailed for three months after publishing two articles written by Maseko that criticized Swaziland’s chief justice.

With this ruling, Africa joins an increasing number of countries and international authorities who affirm that criminal defamation laws should not be used as a tool to restrict freedom of expression, that criminal sanctions, if applied, should only be used under extreme circumstances, that imprisonment should never be an option, and that other penalties should be proportionate. African governments should now heed the ruling and amend their laws, drop pending criminal defamation charges, and free those jailed under such laws. This would be the best news not just for journalists and human rights defenders, but for citizens of countries across the continent who have a right to know what is happening in their countries, and a right to express what they think about it.