At least 14 journalists are under judicial proceedings. Four are in detention. We are witnessing an escalation of repression.

This statement was originally published on article19.org on 13 December 2022.

ARTICLE 19 is alarmed by the increasing restrictions on freedom of expression and press freedom in Algeria, which directly violate the guarantees provided by the Algerian constitution, brought in on 1 November 2020. As Algerians mark the three-year anniversary of the election of President Abdelmadjid Tebboune on 12 December 2019, we call on the Algerian authorities to protect freedom of expression and freedom of the press in accordance with its international human rights obligations.

Introduction

On 22 February 2019, millions of Algerians occupied public spaces in most Algerian cities to express their opposition to former President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s bid for a fifth term. The Hirak protest movement eventually secured Bouteflika’s resignation in April 2019. However, when the movement opposed the holding of presidential elections in December 2019 in the absence of reforms demanded by the people, authorities arrested leading figures of the movement, as well as over a thousand other people.

After the election of President Abdelmadjid Tebboune on 12 December 2019, the repression intensified. The protests stopped in March 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, and there were attempts to resume them on the second anniversary of the Hirak movement in February 2021, but momentum was lost three months later due to repression and its impact on the movement.1

On 1 November 2020, the Algerian people voted with caution, following a low turnout in the referendum, to put in place a new constitution following the popular uprising of the Hirak and the desire to build a freer and more democratic Algeria. However, the adoption of the constitution was contested and with some key political stakeholders failing to participate.

ARTICLE 19 is concerned about the continued deterioration of the human rights situation in Algeria and the restrictions on freedom of expression and on the press. In this briefing, we highlight the main challenges to these freedoms three years after the presidential elections on 12 December 2019 and the establishment of a ‘new Algeria’.

1. ‘There are no prisoners of conscience in Algeria’

Since December 2019, several activists and human rights defenders have been prosecuted after they criticised senior officials and public authorities for infringing their rights and freedoms.

The rising numbers of trials, and the increase in trials initiated on trumped-up or questionable charges linked to expressing an opinion is alarming and signals a deterioration in freedom of expression conditions in Algeria.

.On 31 July 2022, however, President Abdelmajid Tebboune, in a routine interview with the national press, stated that ‘there are no prisoners of conscience in Algeria and (…) the alleged existence of such prisoners is the lie of the century. While recalling that freedom of expression is guaranteed by the Constitution, the Algerian Head of State considers that any person who insults or makes defamatory statements against the authorities ‘must be prosecuted and judged in accordance with the provisions of common law, regardless of their status’.

While the Algerian League for the Defence of Human Rights (LADDH) estimates that in 2022, the number of people who had been detained for voicing an opinion was 330, President Tebboune’s statements have provoked the indignation of human rights defenders in Algeria. Lawyer and human rights defender Abdelghani Badi states that ‘There is no repressive system in history that recognises the existence of opponents detained for their opinions’.2

On 28 January 2022, at least 40 prisoners of conscience in El-Harrach prison in Algiers began a hunger strike, according to lawyers from the Collective for the Defence of Prisoners of Conscience. The strikers denounce their pre-trial detention; the proceedings against them based on Article 87 bis of the Penal Code; as well as the conditions of their detention, with total deprivation of family visits. On 29 January 2022, the Algiers public prosecutor’s office published a press release denying any abnormal situation in the prisons. ‘No strike movement has been recorded within this penitentiary establishment [of El-Harrach]’, the communiqué said. It also threatened to prosecute anyone who relays information despite resistance from the ranks of the lawyers. Moreover, the vast majority of prisoners of conscience have been in pre-trial detention for months or even years, which violates the principle of a fair trial as provided in Article 41 of the Constitution of 1 November 2020, which states that ‘everyone is presumed innocent until proven guilty by a court in a fair trial’.

Some prisoners of conscience were granted a presidential pardon this year, but only in the case of a final verdict. The pardon concerned only about 10 prisoners of conscience. Moreover, President Tebboune specified only one category of prisoners of conscience, namely those convicted of assembling and arrested in the context of the Hirak movement. Tebboune also decided on ‘appeasement measures’ in favour of ‘young people facing criminal proceedings and who are in pre-trial detention for having committed acts of assembly’.3

Finally, several former prisoners of conscience remain under judicial control, including journalists and political leaders such as Khaled Drareni, Said Boudour and Karim Tabbou. They must report to an authority each week, stating where they are residing and working, as well as their other movements. They are restricted in their movements and forbidden to travel. Some are not allowed to speak to the press. This is notably the case for Karim Tabbou.4

2. The fear of returning to Algeria

Outside Algeria, repression is still the order of the day. Activists from the Algerian diaspora are prevented from returning to Algeria for fear of arrest. In a joint statement by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, the Algerian authorities imposed arbitrary travel bans on at least three Algerian diaspora activists in May 2022.

Between January and April 2022, these citizens, of Algerian and Canadian nationality, were arrested and questioned about their links to the Hirak movement. Two were released (Hadjira Belkacem and ’N’, an individual wishing to remain anonymous), but one, Lazhar Zouaimia5, was charged, preventing him from returning home to Canada.

On 19 February 2022, and again on 9 April 2022, the border police prevented Zouaimia from boarding a plane to Montreal. A judge from the Constantine court placed him in pre-trial detention for being an apologist for and financing a terrorist organisation, under Article 87 bis of the Criminal Code. On 30 March 2022, Lazhar Zouaimia was released on bail. On 6 April, the same court changed the charge to ‘attacking the integrity of national territory’, under Article 79 of the Criminal Code. In the meantime, and since his arrest, his telephone has been confiscated. He was acquitted on 5 May 2022 and returned to Canada. In September 2022, he was sentenced in absentia to five years in prison and a fine of 100,000 DA (US$934) by the court in Constantine, Algeria.

ARTICLE 19 considers the travel ban, which has no legal basis, to be arbitrary and runs counter to the rule of law and infringes on several freedoms at the same time, starting with the freedom of movement, which is used by the Algerian authorities as a means of muzzling Algerians’ freedom of expression.

3. Article 87 bis: Elastic terrorism

In a communication submitted to the United Nations Human Rights Committee on 21 December 2021, the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism stated that the definition of terrorism as legislated in the Algerian Criminal Code is contrary to international standards6 in the fight against and prevention of terrorism.

Several arrests and charges in Algeria are now based on the provisions of Article 87 bis. Thus, activists such as human rights defenders Kaddour Chouicha, Jamila Loukil and Saïd Boudour were sentenced on 29 April 2021 by the public prosecutor of Oran for ‘enlisting in a terrorist or subversive organisation active abroad or in Algeria’.

ARTICLE 19 notes that the majority of those recently arrested are prosecuted based on Article 87 bis. There is even a retroactive application of this article. The content of this text is very elastic. The magistrate has full powers to interpret this article and the facts for which the accused is being prosecuted. This elasticity in the definition of terrorism is a violation of a fundamental principle of the rule of law, namely legal certainty and its predictability.

ARTICLE 19 urges the Algerian authorities to review criminal legislation and bring it into line with the provisions of the Constitution and international standards. It calls on the authorities to stop using repressive, catch-all laws to imprison people who have merely exercised their right to freedom of expression.

4. The massive closure of private media

In a media intervention7 on 16 February 2022, President Abdelmadjid Tebboune underlined that there are nearly 8000 journalists working for 180 daily newspapers that are ‘printed without paying any fees’. He specified that ‘there are also about 20 television channels that are considered to be national channels, although this will soon change, because within a month the new law on information that governs the audiovisual field in Algeria will be promulgated’.

This year, several media outlets have ceased publishing, driven to do so by self-censorship and businesspersons being to stop investing in the private media sector. This is the case of the newspaper Liberté, which has been a key player in the Algerian media landscape since its launch in the 1990s. On 6 April 2022, the Société Algérienne d’Édition et de Culture (SAEC) took the decision to dissolve the French-speaking Algerian daily. Its majority shareholder, businessman Issad Rebrab, led this decision. ARTICLE 19 suspects that the reasons for the closure are politically-motivated, as SAEC is a profitable company without financial difficulties. The affair reveals the nature of the political system as well as the vulnerability of the press and the precariousness of the journalistic profession.

The case of the newspaper Liberté is not anodyne. Immediately afterwards, it was the turn of the newspaper El Watan, another major French-speaking Algerian daily.

El Watan was deprived of advertising, its bank accounts were blocked and it found itself under fiscal adjustment. Its contract with the Agence Nationale d’Edition et de Publicité (ANEP), the main distributor of state advertising, was unilaterally broken by the latter, and El Watan has not been able to pay its journalists since January 2022. Although these journalists have denounced this policy of silencing newspapers in communiqués published on the social network Facebook, the authorities remain silent and refuse any financial aid to the newspaper in order to prevent it from disappearing.

In his statement to the newspaper Le Monde, Mohamed Tahar Messaoudi, the director of publication for El Watan, notes with bitterness that El Watan is ‘heading towards definitive closure’, predicting the end of its ‘intellectual adventure’.

ARTICLE 19 reminds Algeria of its commitments to preserve media freedom. Article 54 of the Algerian Constitution guarantees press freedom. Moreover, the Human Rights Council has underlined in its General Comment No. 34 the role States have in promoting media plurality. Under international standards on freedom of expression, states have a positive obligation to adopt a legal and regulatory framework that allows for the development of a free, independent and pluralistic media landscape. ARTICLE 19 calls on the Algerian authorities to ensure that the allocation of public subsidies to the media is organised in a clear and transparent manner within a legal framework that preserves the independence of the media.8

5. Journalism, a high-risk job

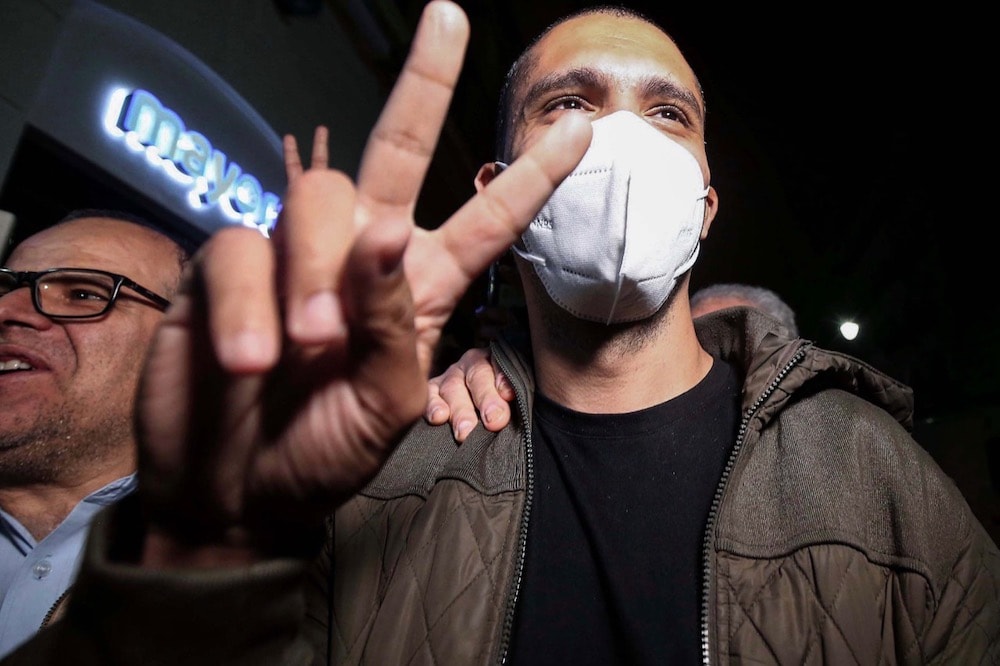

At least 14 journalists are under judicial proceedings. Four are in detention. We are witnessing an escalation of repression.9

Several journalists were arrested and convicted, including Rabeh Karéche, Hassan Bouras and Mohamed Mouloudj, who were arrested by the police and charged with belonging to a terrorist organisation and/or disseminating false information and undermining national unity under the provisions of Article 87 bis.

Khaled Drareni, a journalist and Reporters Sans Frontieres representative in North Africa, states, ‘The obvious regression of press freedom in Algeria now raises the question of the very possibility of exercising journalism in this country. The judicial pressure maintained by the authorities on media professionals creates a climate of fear that pushes them to self-censorship and renunciation.’10

ARTICLE 19 reminds the Algerian authorities of the importance of ensuring journalists and media professionals have the ability to work freely, independently and safely, without hindrance, threats or violent reprisals. Journalists play a vital role in democracy, in the flow of information, and in the promotion and protection of human rights, and their interaction with public opinion is a vital part of these safeguards.