If charged and convicted, the journalists could face prison sentences of one to six years, according to Argentina’s penal code.

This statement was originally published on cpj.org on 23 January 2023.

Argentine authorities should drop the lawsuit filed against journalists Joaquín Morales Solá and Daniel Santoro and their newspapers, and refrain from prosecuting members of the press in retaliation for their work, the Committee to Protect Journalists said Monday.

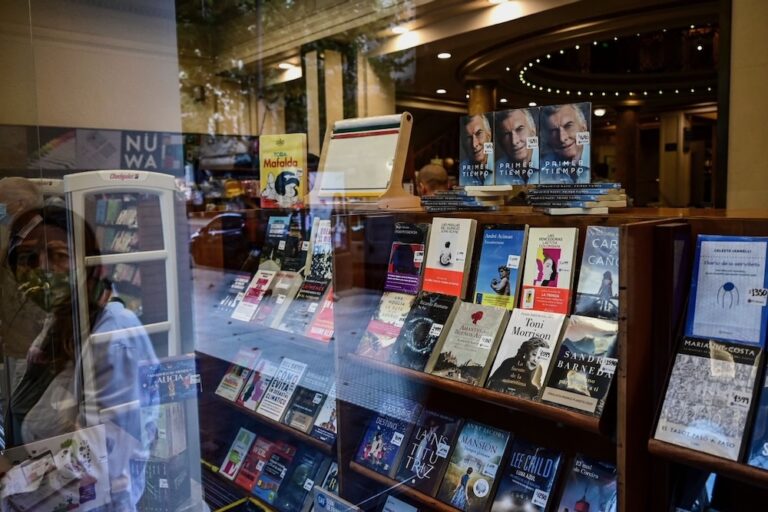

On January 4, Argentina’s Federal Intelligence Agency, known as the AFI, filed a criminal lawsuit against the independent Buenos Aires newspapers La Nación and Clarín, as well as Morales, a columnist at La Nación, and Santoro, the judicial editor of Clarín, according to news reports and the journalists, who spoke with CPJ via messaging app.

The intelligence agency accused the journalists of illegally revealing the names of AFI agents, according to those sources. The journalists each covered the AFI for their respective publications, disclosing the names of military officers working for AFI despite Argentina’s legal ban on armed forces personnel conducting domestic spy operations. Morales and Santoro told CPJ that they denied any wrongdoing and had based their reporting off of documents the AFI had provided to a congressional oversight committee.

“Argentine authorities should drop their lawsuit against journalists Joaquín Morales Solá and Daniel Santoro, and the Clarín and La Nación newspapers,” said Carlos Martínez de la Serna, CPJ’s program director, in New York. “This effort to intimidate journalists is not acceptable, and authorities should refrain from prosecuting reporters in retaliation for their work.”

If charged and convicted, the journalists could face prison sentences of one to six years, according to Argentina’s penal code. In early February, when Argentine judicial authorities return from vacation, a federal prosecutor will examine the evidence and decide whether to proceed with the criminal case, the two journalists said.

“They revealed the names of intelligence agents that clearly must be kept secret,” Agustín Rossi, AFI interim director, said in a January 4 interview. “We filed the lawsuit so that people comply with the intelligence law.”

An AFI spokesperson, who spoke to CPJ on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly on the matter, told CPJ that the lawsuit aims to protect intelligence agents from having their names revealed to the public, which could put them in danger.

Santoro, who has worked at Clarín for 30 years, told CPJ that the lawsuit could lead to self-censorship, calling it “an effort to intimidate journalists so we don’t ask questions and stop investigating the intelligence agency.”

Morales told CPJ that the AFI “is accusing us of breaking the law because we denounced them for breaking the law.”

In a January 4 statement, the Association of Argentine Journalistic Entities said that because Morales and Santoro were investigating possible crimes by a government agency, their work was in the public interest and therefore protected under Argentina’s constitution, which guarantees free expression.

Martín Etchevers, a Clarín spokesperson, told CPJ that it was “disgusting that the AFI is going after journalists for publishing information in the public interest.” In a January 11 editorial, La Nación described the lawsuit as a “ridiculous” attack on press freedom.