December: World authors campaign to release Chinese writers; relative calm in Nepal's media; targeted killings in Philippines and Burma; recognition of digital journalists in Hong Kong.

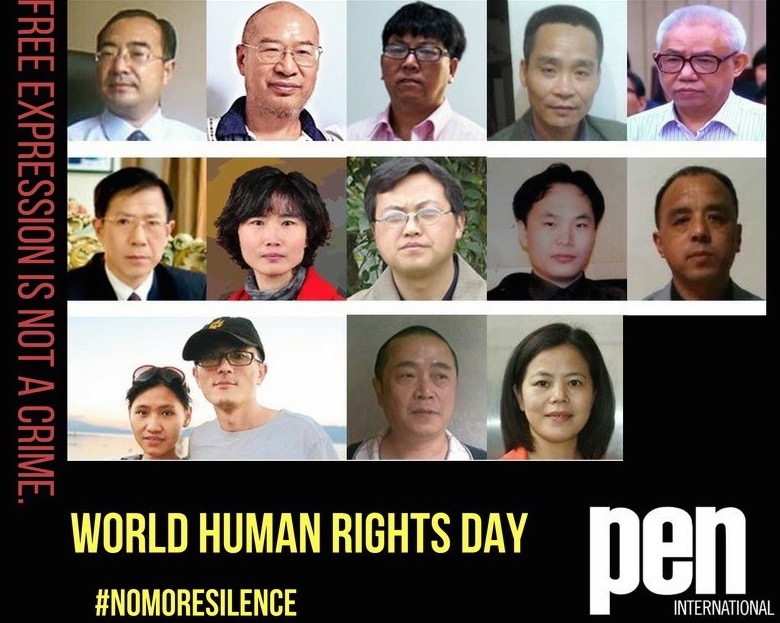

International authors, poets and artists called on President Xi Jinping and the government of China to release imprisoned writers, in conjunction with Human Rights Day on 10 December 2016. Organised by PEN International, the signatories of the letter included Ai WeiWei, Nobel Laureate JM Coetzee, Salman Rushdie, Ma Thida, Margaret Atwood, Salil Tripathi and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who said they couldn’t stand by as “more and more of our friends and colleagues are silenced.” China has among the highest numbers of detained and imprisoned writers; the letter highlights those who are either serving long sentences or under house arrest, like Nobel Peace Laureate Liu Xiaobo and his wife and poet Liu Xia, Uighur scholar Ilham Tohti and veteran journalist Gao Yu, as well as disappeared publisher Gui Minhai. The campaign is an ongoing effort by the global literary community in support of the Chinese writers.

Turkish author Elif Safak tweeted the campaign:

On #humanrightsday international authors & poets ask #China to release silenced critical voices @pen_int @englishpen https://t.co/sad1fHefHI

— Elif Şafak / Shafak (@Elif_Safak) December 10, 2016

Journalists’ safety

In 2016, more journalists were killed in conflict areas and while covering dangerous protests in the year globally, compared to those who were targeted for their work.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, historically, more journalists were murdered as retaliation for their work, but in 2016, the trend had reversed: of the 48 recorded killings, 26 died while covering the conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, Afghanistan and Somalia, while 18 were victims of target killing.

In a third category, those killed while covering political unrests, CPJ noted the two journalists in Pakistan who were killed, along with at least 70 other people, when a bomb was detonated while they were covering a crowd of mourners at a hospital in Quetta. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) said in its year-end report that 93 journalists were killed as a result of bomb attacks and targeted and cross-fire killings during the year, down from 112 in 2015. Twenty-eight of those took place in the Asia Pacific region.

24 media professionals killed in South Asia in 2016: Afghanistan 13, India 5, Pakistan 5, Bangladesh 1 @IFJGlobal https://t.co/JqmOqjYmlJ

— Ujjwal Acharya (@UjjwalAcharya) December 31, 2016

While state agencies and political parties continued to be major violators of press freedom, in Nepal, media freedom groups concluded that there were fewer attacks on the media in 2016, compared to previous years. Freedom Forum (FF) said there were 25 incidents of press freedom violations affecting 75 journalists. This was significantly lower than the 83 cases noted in the previous year.

The Federation for Nepali Journalists also issued its year-end report on press freedom in which it recorded 56 cases of violations, including the hostile takeover of media outlets by political party members. Both organisations agreed that while journalists were still under threat, there were notable positive developments. For example, the introduction of minimum wages for media workers, insurance for working journalists and access to more affordable treatment at government hospitals would go a long way to support the industry, they said.

Targeted killings continued; the Philippines recorded its first journalist killing under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, according to the IFJ. Larry Que, a columnist and the new publisher of Catadunanes News Now was shot in the head on 19 December, as he was entering his office in central Philippines. The killing came after his column criticising local officials for negligence in allowing a shabu (crystal meth) laboratory to be set up in the region. The Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility said that, if proven work-related, Que will be the 153rd case of a journalist killed in the line of duty in the country since 1986.

Reporting on drug-related stories is particularly challenging as Duterte has launched a deadly crackdown on drug offenders. The National Union of Journalists Philippines called on the Presidential Task Force on Violations of the Right to Life, Liberty and Security of the Members of the Media, to immediately investigate Que’s murder.

NUJP urges Duterte admin to solve killing of Catanduanes journo https://t.co/PqEOZyI6v7

— NUJP (@nujp) December 21, 2016

In Burma, Soe Moe Tun, a reporter with Daily Eleven, was killed in the northwestern city of Monywa on 13 December. According to media reports, he is believed to have been targeted for his reports on the proliferation of illegal karaoke bars and illegal logging in the region. Reporters Without Borders called on the authorities to redouble efforts to identify the mastermind behind the killing, as the risk of not identifying the perpetrators increases with time. Three people have been arrested so far. Despite a new democratically-elected government in place, critics say press freedom, access to information and safety of journalists have not seen significant improvements.

Access to information

In a positive development in Hong Kong, the Ombudsman’s office ruled against government policy to deny journalists working with digital only media, access to official government press events. The move was welcomed by the Hong Kong Journalists Association, which had filed a complaint following restrictions imposed on online journalists covering October’s legislative council elections and other official functions. One of the affected media outlets was the Hong Kong Free Press, which issued a joint statement with seven other online media organisations calling on the government to immediately review its restrictions.

I asked GovHK if HKFP will be able to cover the March election, how long their “review” will take & if we can get press releases. Response: pic.twitter.com/KhiMkLys4l

— Tom Grundy (@tomgrundy) December 29, 2016

More censorship on the horizon?

Freedom House warns that given the trends of last year, 2017 could witness increased censorship in China, especially around the party congress later in the year and on any topics that touch on internal struggles for the leadership. It noted that, in 2016, the government issued more directives to protect official reputations and influence coverage of foreign affairs than of domestic economic issues, which had dominated censors the year before.

Freedom House’s Sarah Cook predicts a negative impact on free expression and online privacy as two laws will come into effect – the Cybersecurity Law and the Foreign NGO Management Law. Human Rights Watch said that in an environment where the Chinese government already applied high-handed tactics against its critics, the Cybersecurity Law provided a “veneer of legal legitimacy when it imprisons online critics or shuts down companies.”

China’s growing global influence using soft power has also been observed in Australia. Citing a report by media professor Wanning Sun at the University of Technology, Sydney, Hong Kong Free Press’s Andrew Barclay wrote of the discernible shift in the Australian media from a more critical to a more supportive stance on China. According to the media report, other experts have expressed concern with the lack of critical, political stories on China-Australia relations in the media and the possibility of the Chinese Community Party extending its influence over social media platforms like WeChat, popular among the migrant community.

PEN International