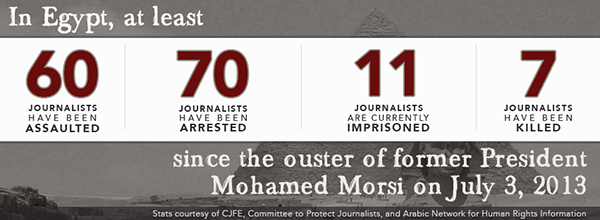

Since the ouster of Mohamed Morsi, at least 60 journalists have been assaulted, 70 journalists arrested, and seven journalists killed, all in the course of their reporting

This article was originally published on cjfe.org on 26 September 2014.

By Alexandra Zakreski

Although they’re arguably the highest-profile detainees, Al Jazeera English journalists Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed are only three of at least 11 journalists currently imprisoned in Egypt.

Since the ouster of Mohamed Morsi, at least 60 journalists have been assaulted, 70 journalists arrested, and seven journalists killed, all in the course of their reporting, according to statistics collected by CJFE, the Committee to Protect Journalists and the Cairo-based Arabic Network for Human Rights Information.

These numbers are disturbing, to say the least. What is perhaps even more distressing is that journalists represent only a small fraction of the total number of prisoners of conscience in Egypt, where security forces have detained students, civil society activists, academics, religious leaders, and human rights defenders in staggering numbers.

The government of President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has at times appeared to soften its stance against free expression and press freedom. Al Jazeera Arabic journalist Abdullah el-Shamy was released in June on medical grounds, after a hunger strike that lasted nearly five months. On September 17, two more journalists were released on bail. Yet for every sign of positive action, there is an opposite reaction; only days after El-Shamy’s release, Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed were convicted of terrorism charges. Similarly, prominent blogger and activist Alaa Abd El Fattah was released on bail September 15, but the draconian anti-protest law which imprisoned him remains extant, and recently sparked a “nation-wide hunger strike” by numerous political parties and journalists.

In an encouraging development, Egyptian government representatives met with members of the National Council for Human Rights (NCHR) and the Ministry of Transitional Justice to discuss the anti-protest law. Following the meeting, it was reported that the government would be drastically amending the law. The next day a cabinet spokesman backtracked, saying that “there are no signs the law will be reviewed for discussion or amendment.” The move was described by an NCHR member as “a political manipulation that we should not see after the revolution.”

In July, the Egyptian Social Solidarity Ministry announced that all non-governmental organizations (NGOs) would need to register themselves with the government before September 2 or their operations in the country would be considered illegal. Registration would empower the government to freeze the assets of these groups and shut them down at a whim, thus stripping them of their independence and ability to remain critical. Following widespread outcry from civil society the deadline for registration was extended, buying NGOs valuable time to contest the policy.

In another example of backsliding, the government then amended Article 78 of Egypt’s penal code to punish any groups (among them NGOs) who accept foreign funding “to commit acts against the state’s interests,” with life imprisonment. In instances where a public servant is involved, the accused can now face the death penalty. Considering that the Egyptian regime is inclined to interpret any criticism as an attack on the state, it’s not hard to see how the amended Article 78 could be used to ensnare human rights groups, civil society activists, and more.

Overall, the Egyptian government has perpetrated extensive human rights violations against countless individuals exercising their legitimate right to free expression, and they appear to be more concerned with keeping up appearances than establishing substantive democracy. A recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) revealed that Egyptian security forces premeditated the violent killing of demonstrators protesting the ouster of former president Mohamed Morsi outside of Rab’a al-Adawiya Mosque on August 14, 2013. In response to the report, the Egyptian government accused HRW of conducting an illegal investigation and violating Egypt’s state sovereignty, and then prevented two HRW executives from entering the country to deliver the report.

To this day, no security officer present at the “Rab’a Massacre” has been investigated for their part in the slaughter of at least 817 largely peaceful protesters.

International attention has recently turned to the escalating crisis of Islamic State militants in Syria and Iraq; with Egypt’s role as an “important partner” in the coalition fighting them, there is an acute danger that the human rights violations perpetrated by the Egyptian government will fade into the background. Fundamental rights and freedoms cannot be made secondary to security.

Share the graphic above and lend your voice to the call for greater respect for free expression in Egypt.