Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is continuing to analyse the attacks on the Brazilian media by President Bolsonaro, his family and other members of his inner circle. Supported by key statistics, this latest analysis covers the first six months of 2021, in which the attacks have intensified.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 27 July 2021.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) is continuing to analyse the attacks on the Brazilian media by President Bolsonaro, his family and other members of his inner circle. Supported by key statistics, this latest analysis covers the first six months of 2021, in which the attacks have intensified.

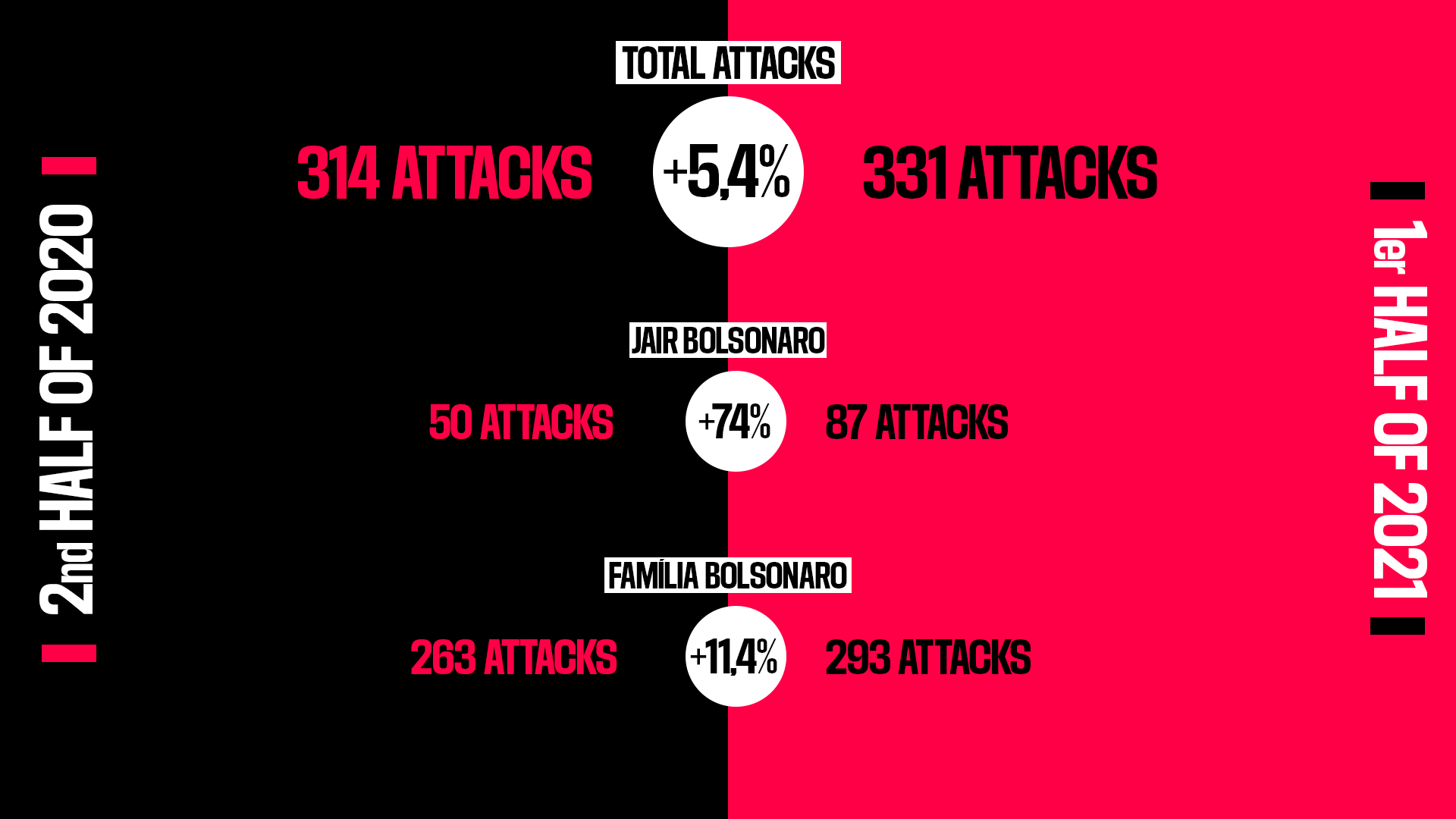

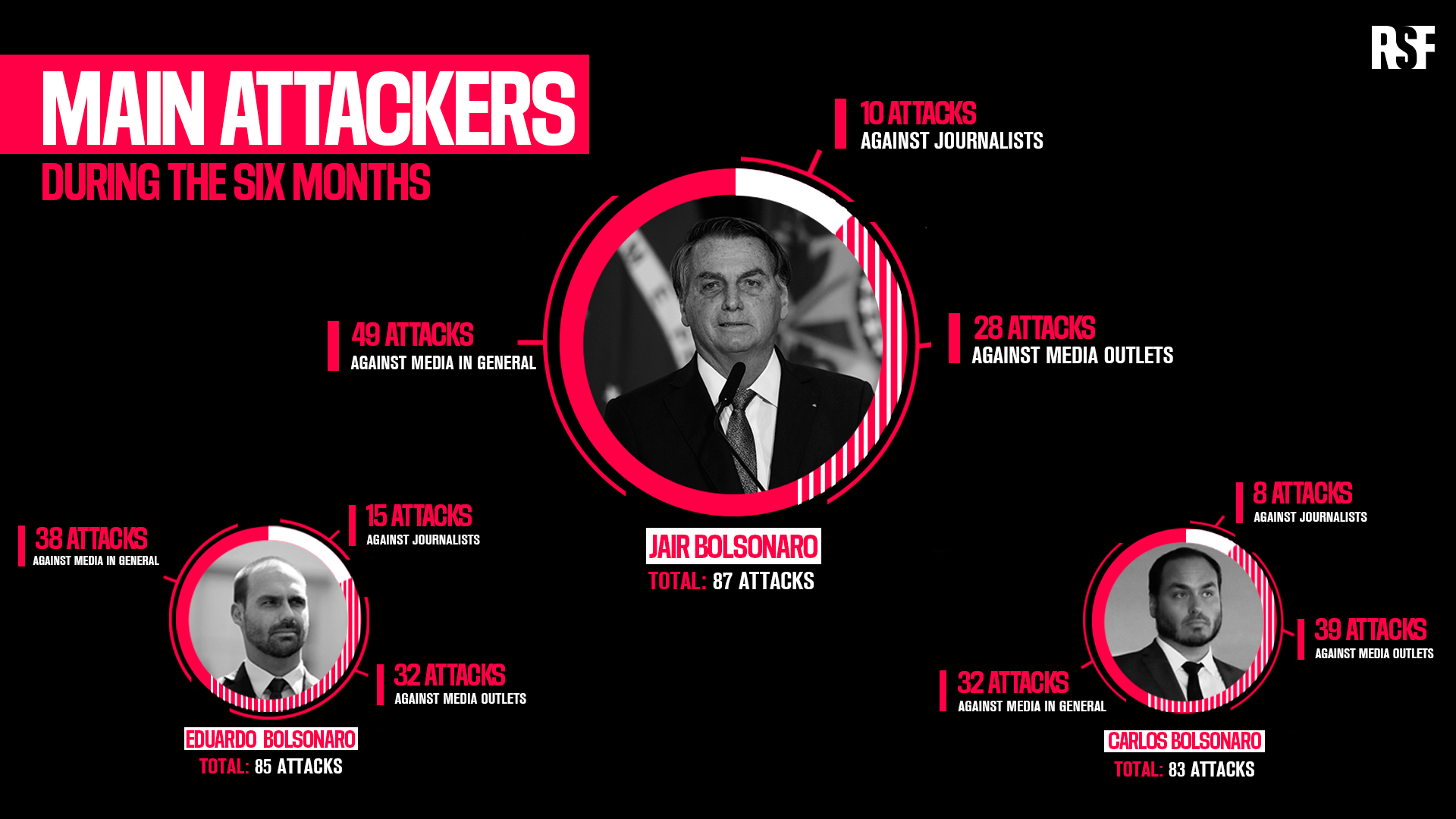

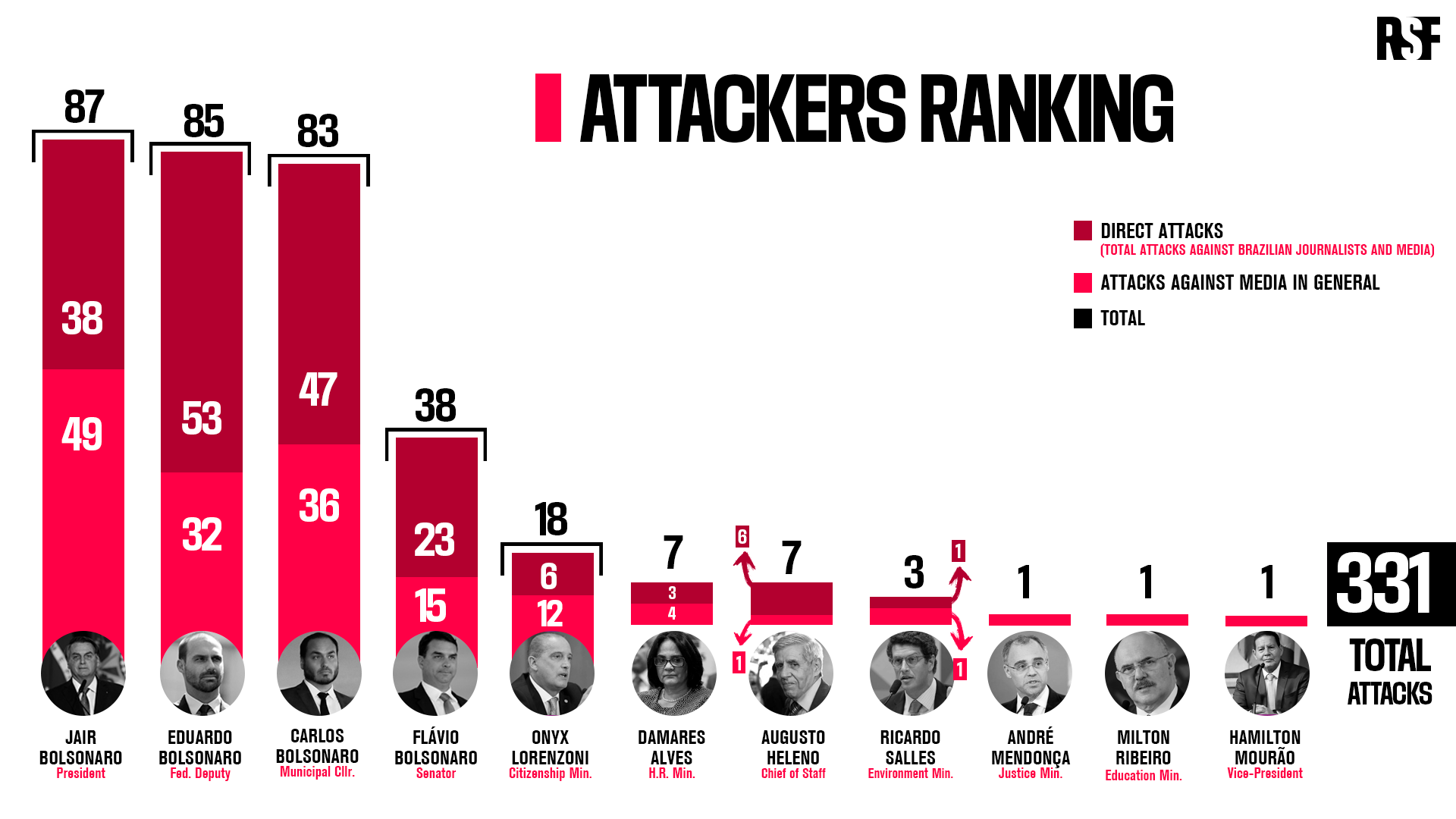

The figures are enough to make your head spin. The number of attacks on the media by President Bolsonaro in the first half of 2021 increased by 74% over the second half of 2020. Jair Bolsonaro targeted the media 87 times, which made him the system’s leader predator, although his sons were not far behind. Rio de Janeiro city councillor Carlos Bolsonaro was responsible for 83 attacks on the media (an 84.4% increase on the second half of 2020), while Federal deputy Eduardo Bolsonaro attacked the media 85 times, which – although a big score – was 41.4% down on the second half of 2020, when he was responsible for 145 attacks.

CHART 1: Total attacks in 1st half 2021 vs 2nd half 2020

CHART 2: Leading attackers podium

CHART 3: Attackers ranking

In all, RSF’s staff have tallied a total of 331 “Bolsonaro system” attacks by the Brazilian media, a 5.4% increase on the second half of 2020. The figures are bad enough but the content of the attacks are even worse. As the Covid-19 pandemic has continued to have a devastating effect in Brazil because of the federal government’s mishandling of the crisis (with a death toll of more than 550,000 on July 26th), the attacks by the president and his close allies against journalists have grown stronger and more varied, sometimes attaining an unimaginable level of vulgarity and violence.

For this report, RSF established a partnership with Cartooning For Peace, an international network of socially and politically committed cartoonists. Three Brazilian cartoonists, Aroeira, Amorim and Machado, were particularly interested in the subject of the Bolsonaro system’s attacks on the media and agreed to illustrate the report. See details here.

Cruder and more virulent attacks

President Bolsonaro began 2021 with a flourish. Surrounded by supporters at an event on 27 January about federal government spending (and amid a controversy about abnormally high spending on condensed milk), he said “condensed milk cans should be shoved up the backsides of the press” to cheers and applause from the crow, including then foreign minister Ernesto Araujo. He returned to the subject during his weekly Facebook Live broadcast on 5 February, displaying a big can of condensed milk and saying it was “better suited to the Fake News media.”

He lost all self-control at a press conference during a visit to Sao Paulo state on 21 June, insulting a journalist with the Globo media group’s TV Vanguarda who asked him why he was not wearing a mask when he arrived at the site of the visit. “Shut up (…) Globo is the shitty press, the rotten press,” he shouted, after deliberately removing his mask in order to reply.

He lost all control again on 25 June when asked about suspicions of federal government fraud in connection with the purchase of Covid-19 vaccines, telling Rádio CBN journalist Victória Abel to “go back to university, to high school, then to nursery and then you can be reborn.” During the same press conference, he told journalists to stop asking him stupid questions.

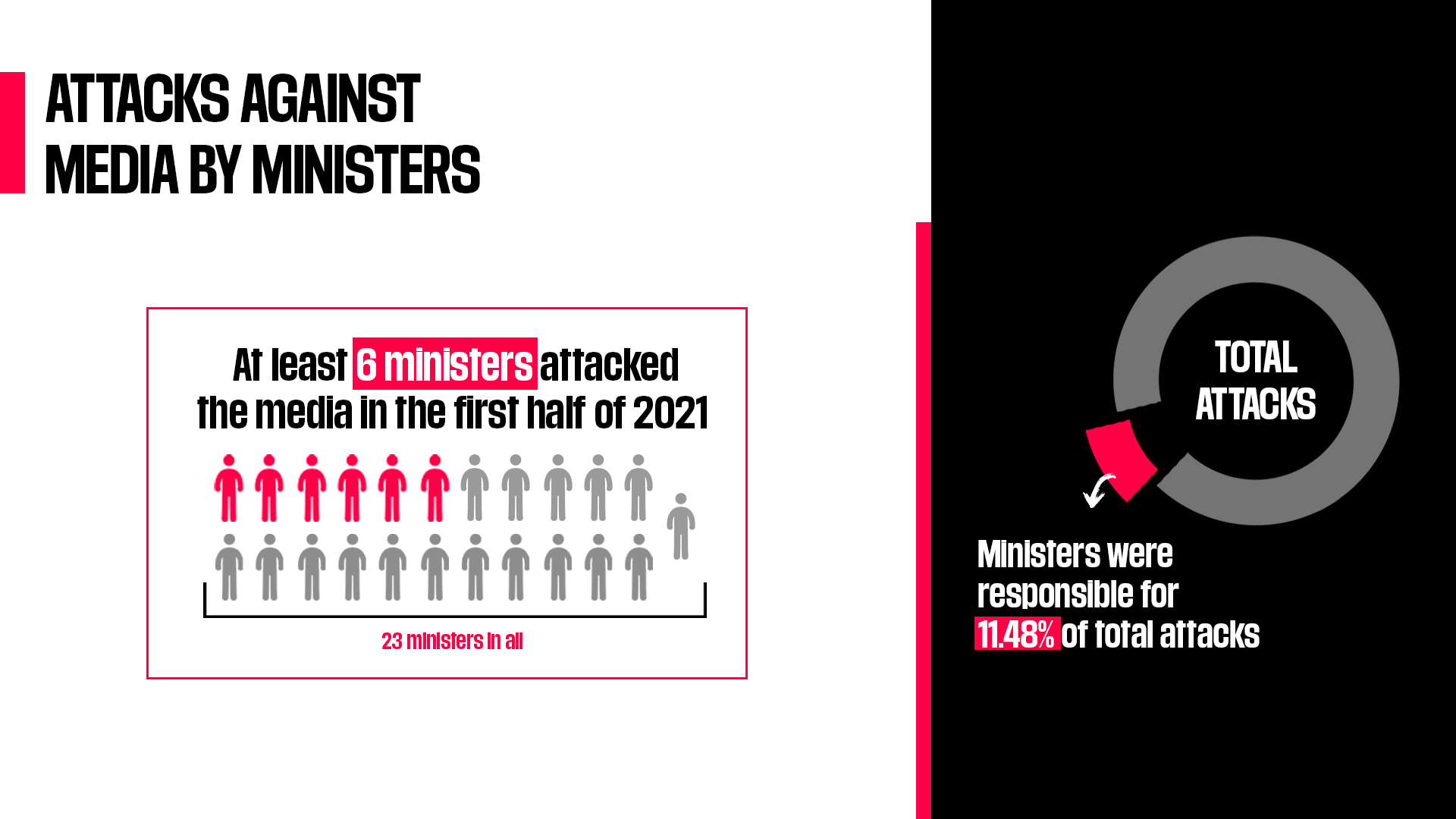

CHART 4: Attacks by ministers as share of total

The most offensive government ministers include Onyx Lorenzoni, who is the president’s chief of staff, and Damares Alves, the minister for women, family and human rights. The former was responsible for 18 attacks on the media during the past six months, while the latter was responsible for seven.

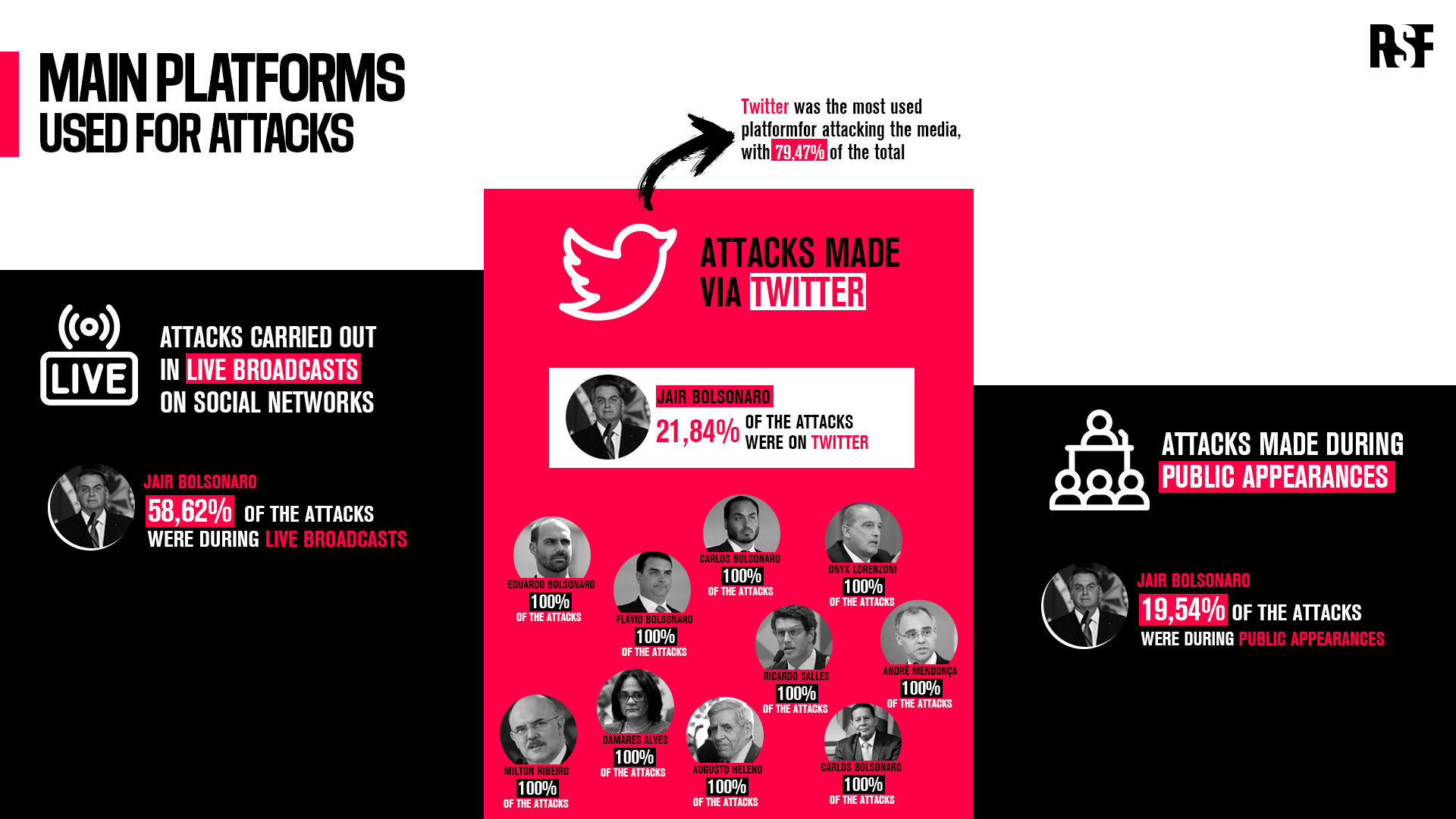

Twitter and Facebook Live – favourite attack platforms

CHART 5: Breakdown of attacks by platform

The platform preferred by the Bolsonaro system’s attackers is Twitter. This venting outlet for Bolsonaro supporters is where 80% of the attacks on the media take place. The president limits his own exposure on Twitter by blocking most of the accounts that annoy him. They have included RSF’s since it published its 2020 round-up of attacks. According to a survey by the Brazilian Investigative Journalism Association (ABRAJI), he is the public official who blocks the most journalists’ accounts on Twitter –240 more accounts than the average member of the Chamber of Deputies.

After being censored by Twitter several times in 2020, especially for violating lockdown measures, the president has made more use of another platform for insulting and attacking journalists in 2021. Every week he talks live from the Alvorada presidential palace on the presidential Facebook channel on the news topics of his choice. Retransmitted live on YouTube, this broadcast allows him to talk directly to his public without being questioned or contradicted, to spread his anti-media rhetoric, lambasting media which, according to him, constantly “lie and disinform,” especially about the pandemic’s impact in Brazil.

Jair Bolsonaro staged frontal attacks on the media during 19 of his 24 Facebook Lives during the first half of 2021. In all, 59% of Bolsonaro’s attacks on journalists took place on Facebook, as against 22% on Twitter and 19% during public appearances.

He has used this space to construct new narratives about controversial subjects, to play brazenly with the facts, to project his “truths” and to fabricate disinformation in the service of his and his government’s interests, systematically holding the media responsible for all the country’s problems – lockdown measures, vaccination and so on.

He has, for example, used it to provide false information and medically unsound recommendations about an early treatment for Covid-19 and the use of chloroquine. The Facebook Lives of 14 January and 12 February were blocked by YouTube, which regarded his statements as tantamount to disinformation. For the same reason, YouTube decided on 21 July to take down 14 of the Facebook Lives that he had broadcast in 2020 and 2021.

CHART 6: The most attacked media

CHART 7: The Bolsonaro system’s favourite female victims

Women journalists – still favourite targets

As in 2020, women have continued in 2021 to be the targets of the Bolsonaro family’s primitive and crass machismo (constituting 6.1% of the attacks by the president and his three sons). On 2 June, he described CNN Brasil anchor Daniela Lima – one of his favourite targets – as a quadruped, triggering an avalanche of misogynous and despicable attacks against her on social media. TV Vitória journalist Marla Bermudes was the target of a smear campaign and received death threats on 31 March after Carla Zambelli, a federal parliamentary and a strong supporter of President Bolsonaro, accused her in a video of “manipulation” and of “turning cemeteries into recording studios.”

Patricia Campos Mello, a regular target of attacks since the 2018 presidential election, meanwhile won two lawsuits – one on 21 January against Eduardo Bolsonaro and the other on 27 March against Jair Bolsonaro – as a result of which they were ordered to pay her damages for their sexist and degrading comments about her.

Journalists assigned to the presidential beat in Brasilia, who had been the victims of violent public humiliations by government supporters in 2020, were also subjected to the president’s hostility during the first six months of 2021. As a result of a complaint filed by RSF and its allies in Brazil in 2020 about the vulnerability of these journalists, the federal prosecutor’s office issued a request on 3 May for measures to be taken to reinforce their security.

Ranked 111th in RSF’s 2021 World Press Freedom Index, Brazil has joined those countries that are coloured red on the world press freedom map because their situation is classified as “bad.” President Bolsonaro was included in the list of predators of press freedom that RSF published on 2 July.