The New Year is arriving with little to celebrate in Brazil: activists are warning that the new president poses a serious threat to human rights.

For Jair Bolsonaro everything is black and white. There is nothing in between, no middle way, no consultation, no dialogue. At least that’s the way a half dozen human rights organisations that spoke with IFEX described the incoming Brazilian president, who will take power on 1 January.

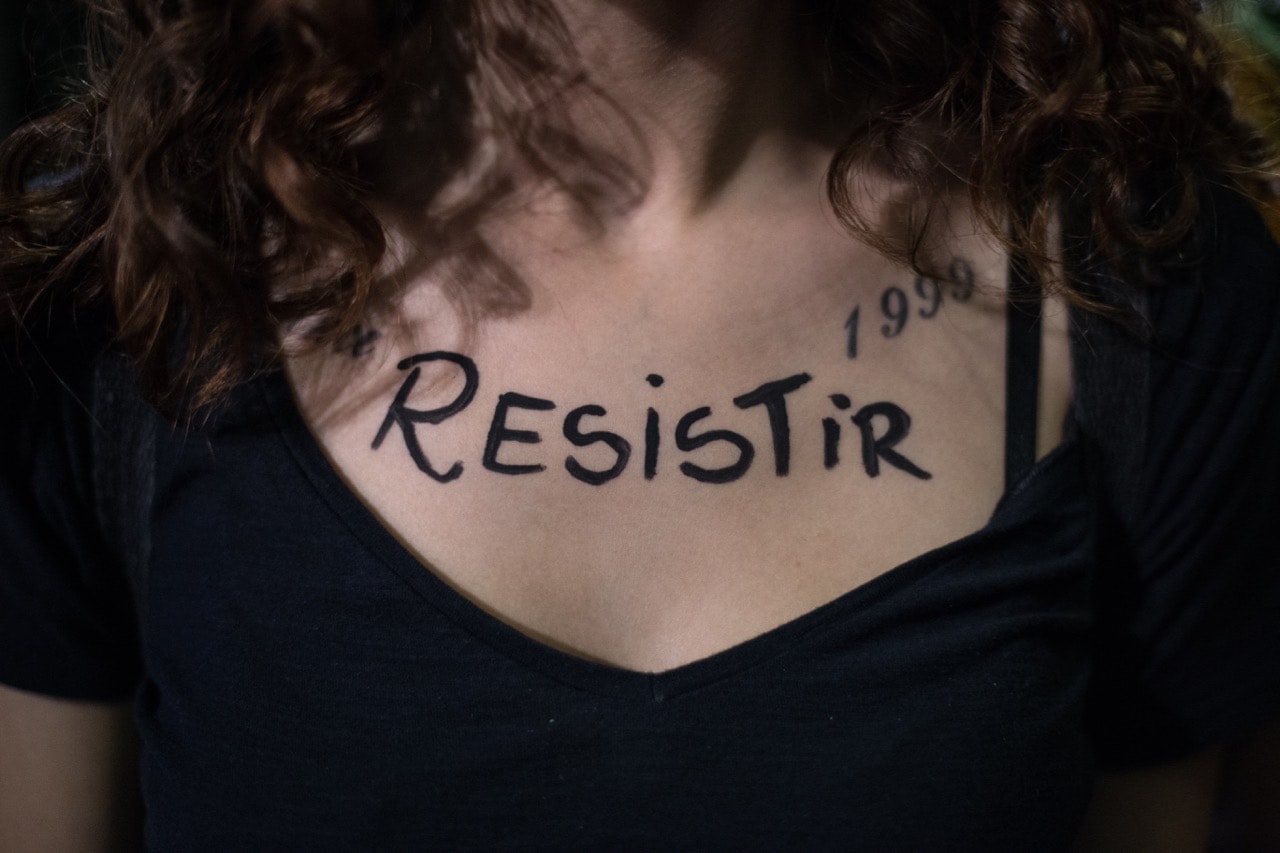

With this in mind, Brazilian activists are preparing to face what they say will be four long years of “organised resistance”. Gone are the days of promoting greater openness for the rights to free expression and non-discrimination against minorities, as well as equality of conditions and respect for journalists and the press.

Now there has to be “resistance” to the “ultra-right” onslaught and the “hate speech” promoted by Bolsonaro, in an effort to avoid losing ground. This is the way the specialists who spoke to IFEX see it, describing the country as “shuddering” and deep in “uncertainty.”

The greatest fear? Not knowing if the new president will carry out everything he said during his election campaign.

Bolsonaro’s attitudes toward minorities and the free press are similar to those of US President Donald Trump. This is disconcerting to organisations that have “never before seen” attitudes in Brazil such as direct and specific attacks on a journalist, constant confrontations with the press or “intolerant” and “homophobic” statements.

Thus far, Bolsonaro has been true to his word, announcing the elimination of the Ministry of Labour, the government body in charge of regulating labour relations.

The “Bolsonaro effect” is not a warm sensation: fearful of what could happen in 2019, hundreds of homosexual couples are rushing through the paperwork and moving their wedding dates up in order to marry in 2018.

In addition, real and on-line attacks on journalists and activists who are critical of Bolsonaro have increased, generating fear and self-censorship within an “atmosphere of hate” that, according to the organisations’ warnings, is encouraged by the incoming president.

Hate speech and attacks. “Everything is in turmoil. The president elect is threatening the press all the time. He has already announced that the São Paulo-based newspaper Folha will not carry government announcements. These types of comments are making us very concerned,” Cristina Zahar told IFEX. Zahar is the executive secretary of IFEX member, the Brazilian Association for Investigative Journalism (ABRAJI).

“The situation is very difficult. We don’t know if he is going to carry out what he says. Some members of the press have folded in the face of his discourse, but others are remaining firm. And we as an organisation are in the middle, expectant without know if he is going to carry out everything he says, which is malicious. We are preparing for four very combative years,” Zahar said.

“The situation is going to be very tough. The word that now defines Brazil is uncertainty, which is the worst. We still don’t know what is going to happen,” she added.

Zahar believes that activists will not abandon the country with the arrival of Bolsonaro and his ideology against the rights agenda. “I think the dominant position will be one of resistance,” she added. “These will be years of struggle to try to avoid losing ground that was previously won.”

According to the activist, the “hate speech” promoted by the president elect, which was a fundamental part of his campaign, “has already had a negative effect” as evidenced by an increase in aggressive actions against journalists and the press.

“In our monitoring we have documented about 150 cases of violence against journalists. If the hate speech continues, the violence will not diminish. What is peculiar in Brazil is not that the president is bothered by some media outlets, but rather that he promotes this hate speech against them,” she said.

“This signifies the rebirth of right-wing populism in Brazil. We already lived through more than 20 years of dictatorship. It is as though they are now taking up that stance once again, stimulating hate speech against the media and minorities,” she added.

Increase in violence. Laura Tresca, the executive director of ARTICLE 19 Brazil, also an IFEX member, explained that “there will be an increase in violence in general, but in particular when it comes to issues related to land and the environment. Activists working in those areas will be the most affected. We will have to strengthen our actions to protect both them and human rights defenders.”

She went on to say that “another thing that has been assessed is that the hate speech will continue. Hatred has a different effect in our culture because we are typically very cordial. To deal with this hate speech we will have develop different, non-European standards. The LGBTIQ population will be the most affected, given the homophobic stance adopted by Bolsonaro.”

According to Tresca, “Press freedom will be threatened at the institutional level. Like Donald Trump, Bolsonaro uses the term fake news to discredit the press. Having the president attack a specific journalist is a new phenomenon in Brazil.”

She further added that this type of administration and its “prejudiced and hateful discourse against human rights” means that organisations will have to take on a more active role, with a range of strategies. “Bolsonaro will try to create an uproar with strong statements, while implementing horrible policies. We need to be attentive to this with observation and constant monitoring.”

Tresca said that the role of digital platforms “will be fundamental” in ensuring protection of minorities and their rights.

“We feel ready to face these violations, the increase in repression of social action. We are going to carry out workshops on holistic security, which will include the issue of on-line violence. We will keep working with women and commentators, as well as the LGBTIQ community,” she noted.

Bolsominions and Trump. Journalist Andrew Downie, the Committee to Protect Journalists’ (CPJ) Brazil correspondent, told IFEX, “There is certainly concern over Bolsonaro’s tone and discourse, especially when it comes to fake news and its growth on WhatsApp.”

“There have been attacks on journalists who are critical of Bolsonaro, mainly on-line attacks. This has been going on for a number of years with the growing polarisation of society, especially since the dismissal of (former president) Dilma Rousseff,” he noted.

According to Downie, “Journalists think twice before giving an opinion and stating their position. There is even a name for the Bolsonaro’s army of followers: Bolsominions, referring to the animated film characters. They form an on-line attack troop that goes after journalists who criticise the president elect. They don’t generally attack the content, but rather the person.”

“There is real concern because the situation is very complicated, there is a lot of tension. We will see what happens with journalists and media when Bolsonaro takes office. He is not a person who measures his words before speaking. Like Trump, he threatens the media and this influences the general public,” Downie said.

The head of Reporters Without Borders’ (RSF) Latin America desk, Emmanuel Colombié, told IFEX that Brazil “continues to be one of the most violent countries in Latin America when it comes to practicing journalism.”

“In 2018 four radio station journalists were killed. There is also a climate of impunity that is fed by the omnipresent corruption, which makes the work of journalists even more difficult,” he noted.

Colombié is based out of Río de Janeiro, where the RSF office is located.

“Bolsonaro’s election was marked by a large number of attacks on press freedom. The country is immersed in hate speech, which makes journalism work more and more complicated. RSF is very concerned about this situation. We call on the new president to understand the value of a free and independent press, instead of vilifying it,” he added.

“We have received many reports of attacks on the press. And attacks on the international press are a new phenomenon, in which Bolsonaro supporters have told them to go back to their countries or called them communists,” Colombié said.

RSF’s action plan will consist of “waiting to see how the new government will organise itself”, seeing what its attitude regarding freedom of expression will be. The organisation is, however, also involved in strategic planning, preparing itself for “the worst scenario.” Its strategy will be characterised, among other thing, by demonstrations, new alliances between organisations and reports and conferences to denounce specific issues.

A unpleasant mystery. According to the programme coordinator for Conectas Human Rights, Camila Asano, “Bolsonaro found a space to grow his platform as a candidate in the midst of a climate in which the country’s citizens are deeply disenchanted with Brazilian politics.”

“How things will be under the Bolsonaro government is still, however, a mystery. Judging by his speeches, the panorama that is being drawn is not at all pleasant: repression of social movements and restrictions on the space in which civil society can act are on the agenda. The challenge now is to strengthen strategies for action and monitor the government’s actions even more closely, including not just the Executive but also the elected senators and members of the Chamber of Deputies,” Asano noted. She also agreed with the other colleagues who were interviewed in noting a rise in threats and violence against minorities.

“There are reports of violence perpetrated by unidentified individuals in the streets or even by relatives or work colleagues. We hope the wave of violence does not gain strength, but we know that this could happen. Bolsonaro’s violent discourse legitimises hate speech and acts of hatred that should be condemned and punished immediately,” she added.

According to Asano, Bolsonaro “already gave indications that treatment of the press will follow the tradition of Donald Trump.”

In addition, Asano warns that proposed legislation that had been halted and that aims to criminalise social movement actions is being resurrected. “If these scenarios come to fruition, they will constitute a strong blow to freedom of expression and freedom of association. Brazilian civil society is already united and is working on ways to stop the progress of laws that restrict rights.”

Finally, Asano added that “thus far we have been successful, but it is difficult to predict how things will be next year.”