Suna Venter's broken heart, silencing Sudan's FIFA suspension, the unsolved case of Burundi's Jean Bigirimana, policing police in Zimbabwe and more from Somalia, Senegal, Nigeria and South Sudan.

July was an ominous month for free expression on the continent. In Southern Africa, the trend was reflected in legislation as much as it was in attacks on journalists.

Emergency censorship

On 5 July 2017, Zambian President Edgar Lungu initiated a “state of threatened public emergency” following a series of arson attacks that Lungu believes opposition party supporters backed.

The International Press Institute (IPI) warns that the emergency powers – in place for 90 days – could have a significant impact on publications’ abilities to publish freely.

“During this period, police will regulate and prohibit publication and dissemination of matters [that are] pre-judicial to public safety,” Inspector General Kakomana Kanganja said on 15 July, noting that they may limit certain publications and social media later “when people are abusing.”

“Given developments in Zambia in the last year, the partial state of emergency would seem to be part of a broader effort that we have observed to silence critical voices, including the country’s remaining independent media outlets,” IPI Director of Advocacy and Communications Steven M. Ellis warned in a statement.

Policing police

In neighbouring Zimbabwe, reporters asked police to offer them protection…from police officers themselves.

On 27 July 2017, NewsDay journalists Obey Manayiti, Shepherd Tozvireva, Abigail Mutsikidze, and their driver, Raphael Phiri were attacked and detained by police after documenting an encounter between police and members of the public in Harare’s business district.

The journalists marched to Harare Central Police station the following day, where they discussed the incident with Inspector Ziburubudu and Media Institute of Southern Africa (MISA)-Zimbabwe Legal Officer Farai Nhende. In a statement, MISA Zimbabwe condemned the events of 27 July, noting that “this abuse of authority by the police [is] seemingly aimed at blocking their unflattering law enforcement practices from filtering into the public domain.”

Suna Venter’s broken heart

“I’m angry at the line managers who ignored each and every e-mail I wrote about your safety… The spokespeople who used the mighty platform of the SABC to belittle you; who said the death threats against you were a police matter and not concerning the corporation…They ignored you when you asked for advice on your health situation. And now you’re dead.”

The quote above is from an open letter written by South African Broadcasting Corporation journalist Foeta Krige to his colleague Suna Venter, who was found dead in her apartment on 29 June 2017.

The 32-year-old news producer died after being diagnosed with a condition called stress cardiomyopathy, also known as “broken heart syndrome.”

Venter’s family believes that her condition – caused by prolonged periods of intense stress – was a direct result of the numerous attacks, threats and legal battles that she had endured since 2016.

Venter was part of a group known as the “SABC 8” who were fired last year after speaking out against an order that prohibited SABC journalists from broadcasting footage of violent protests.

In a statement released in May 2016, SABC Chief Operating Officer Hlaudi Motsoeneng said that airing videos of violence directed at public institutions “could encourage further violence.”

South Africa’s high court subsequently ordered a lift on the footage ban and declared the journalists’ dismissal to be unlawful, but the threats against Venter and her colleagues continued. Venter’s family released a statement detailing what the young journalist endured over a year: “Her flat was broken into on numerous occasions, the brake cables of her car were cut and her car’s tyres were slashed. She was shot at and abducted – tied to a tree at Melville Koppies while the grass around her was set alight.”

Venter’s death provoked outcry from fellow journalists and civil society at large, as is evidenced by the tweets below:

Suna Venter’s family calls for end to intimidation of journos https://t.co/Dhv1Z4cEfi pic.twitter.com/vo8AK5aaMR

— Eyewitness News (@ewnupdates) July 7, 2017

Anti-media sentiment is dangerous in these tense times. Journalists must be protected. What happened to #SunaVenter cannot happen again. https://t.co/5ShOVb94ee

— The Media Online (@MediaTMO) July 10, 2017

Venter’s death was not the only shocking event to happen to South African journalists on 29 June.

On the same day, the home of Tiso Blackstar Group editor Peter Bruce was picketed by Black Land First (BLF) activists, IPI reports. The activists wrote “land or death” on Bruce’s door and assaulted Business Day journalist Tim Cohen on site.

The following day, BLF released a statement announcing that they were targeting “racist” journalists and the “covering up of white corruption under the guise of journalists.”

The South African National Editors Forum (SANEF) Chairperson perceived the threats as an attempt to silence the media on numerous issues, including the Gupta family – who are reportedly very influential on government affairs. Numerous South African publications postulate that BLF has ties to the Guptas.

On 7 July 2017, a Johannesburg court granted SANEF a legal request to prevent BLF from “gathering outside threatened journalists’ homes, from threatening them with violence in social media and from inciting harm against them in public interviews.”

Lawrence Okojie’s mysterious death

Suna Venter was not the only journalist who was mourned in July.

On 9 July 2017, Lawrence Okojie’s body was found in a morgue in Benin City, Nigeria.

Reports cited by the International Press Centre (IPC) say that the Nigerian Television Authority journalist was last seen on his way home from work on the evening of 8 July. The search team later discovered his body with gunshot wounds.

Okojie is the second Nigerian journalist to be killed since April 2017, according to the Media Foundation for West Africa (MFWA).

Lanre Arogundade, Director of IPC, commented on the killing in a statement: “It is one killing too many. It is very sad that journalists are still being murdered in cold blood with no one so far prosecuted and convicted for the acts.”

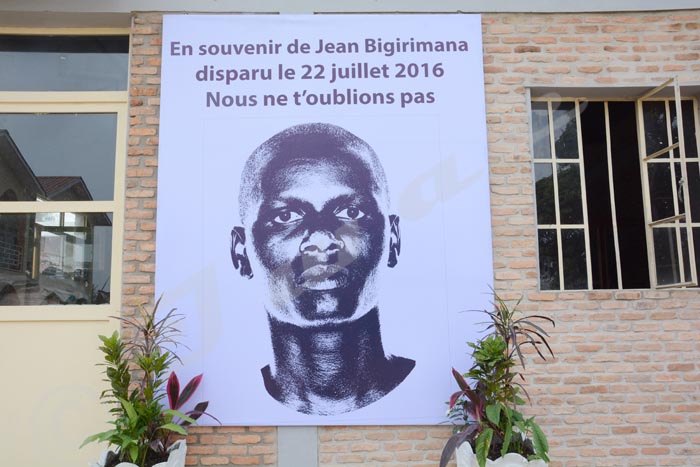

Where is Jean Bigirimana?

July marked one year since Iwacu news website journalist Jean Bigirimana disappeared in Burundi.

On 22 July 2016, the journalist left his home to meet a contact and told his wife he would be home in time for lunch, but she never saw him again. Witnesses say they saw Bigirimana being arrested by members of the National Intelligence Service, and, a few days later, Iwacu employees found two unidentifiable bodies in a ravine.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) reports that authorities have failed to conduct a proper investigation into his case; in advocating for one, Bigirimana’s wife has herself become the target of threats.

“It is high time for this investigation to be completed so that we can finally find out what happened to Jean Bigirimana,” said Clea Kahn-Sriber, the head of RSF’s Africa desk.

Football and “insurrections”

July was rife with censorship in Sudan and South Sudan.

FIFA’s suspension of the Sudan Football Association’s membership on 6 July 2017 was not a development that Sudanese authorities wanted to shout from the rooftops – or read about, for that matter. CPJ reports that the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) ordered the editors of sports newspaper Al-Sada to remove reports about the FIFA suspension. The NISS also confiscated all copies of other sports newspapers from printers on 10 July, and subsequently instructed all publications not to publish information that “targeted” officials associated with the dispute. The FIFA suspension was lifted on 13 July 2017.

The free expression landscape was not much better south of the border. On 17 July 2017, South Sudan authorities blocked the Sudan Tribune and Radio Tamazuj’s websites. Minister of Information Michael Makuei Lueth told CPJ that the sites had been blocked for publishing content that was “subversive” and that the situation would not change until “those institutions behave well”.

In a statement, the Association for Media Development in South Sudan (AMDISS) called the website bans “an attack on freedom of expression [that] does not encourage the spirit of national dialogue and cohesion.”

The website blocks came after the Director of the South Sudan Broadcasting Corporation was detained for over a week after failing to broadcast a state of the nation speech by President Salva Kiir.

Hard pressed for words

On 13 July 2017, Somalia’s council of ministers endorsed a new media bill that the National Union of Somali Journalists (NUSOJ) has described as “harsh” and “seriously damaging for the media.”

In a statement, NUSOJ described certain provisions they are concerned about, including hefty fines for defamation, a requirement for all journalists to register with the Federal Ministry of Information, and the need for professional certification for someone to be considered a journalist.

On 19 July 2017, members of the African Freedom of Expression Exchange (AFEX) petitioned the Somali president to not pass the bill into law by parliament and to “adopt policies and measure suitable for the practice of journalism in Somalia.”

West Africa is not without its share of controversial media laws. In late June, Senegal passed a new press code that the MFWA has described as being “one step forward, two steps back” for media freedom.

In a statement, the MFWA highlighted that of Article 192 of Senegal’s new press code is of particular concern to the media community. Article 192 states that “a district chief executive and other authorities can suspend a media house if a publication is deemed to be a ‘threat to the national security.'”

Suna Venter, part of the SABC 8, campaigned against censorship in South AfricaSuna Venter/Facebook

A photo of disappeared Burundian journalist Jean Bigirimana hangs on the wall of the Iwacu building. “In memory of Jean Bigirimana who disappeared on 22 July 2016. We will never forget you.”Iwacu