Burundi's landscape, prior to the referendum to revise its constitution, featured divisive language, hate speech, intimidation, threats and violence against the media, including the banning of broadcasting stations.

This statement was originally published on rsf.org on 16 May 2018.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) condemns the intimidation and arrests of journalists and the broadcast bans that have reinforced the climate of fear for Burundi’s media, increased the constraints on reporting and prevented proper coverage of the campaign for tomorrow’s referendum on a controversial constitutional amendment.

President Pierre Nkurunziza, who now has his party call him the “eternal supreme guide,” will be able to rule until 2034 if the proposed amendment is adopted.

The start of the official campaign on 4 May 2018 was marked by a new turn of the screw by Burundi’s authorities in the form of a six-month ban on local broadcasting by the BBC and VOA, two of the country’s main international radio stations, for “breaches in professional ethics.”

Since then, acts of intimidation of journalists have occurred throughout the campaign. The reporter Jean Bosco Ndarurenze was expelled from a ruling party meeting in the northern city of Kirundo on 7 May. His audio recorder was confiscated and was then returned on the condition that its contents were deleted.

Radio Insanganiro reporter Pacifique Cubahiro and his cameraman suffered a similar fate last weekend when they tried to do a report on the massacre of 26 residents of a village in the northwest of the country. They were briefly arrested and their recorded video material was seized.

On 9 May, journalists with the Renouveau Burundi newspaper were prevented from covering members of the public collecting their voter cards from the city hall in the capital, Bujumbura.

“Interviewing government opponents means exposing yourself to the risk of reprisals by the authorities,” a Burundian journalist told RSF. “Since the start of the crisis in 2015, we have gone from fear to resignation.”

“Journalists who have tried to cover this campaign in an impartial manner have been called enemies of the nation at a time when the media are already heavily muzzled,” said Arnaud Froger, the head of RSF’s Africa desk. “A democratic and credible referendum is impossible in a country in which the media are gagged and journalists are subjected to constant intimidation.”

A few media outlets survive

Dozens of Burundian journalists fled into exile after an attempted coup d’état against President Nkurunziza in May 2015. Since then, Burundi’s once rich and varied media landscape has been reduced to a few outlets that still manage to provide independent local news coverage.

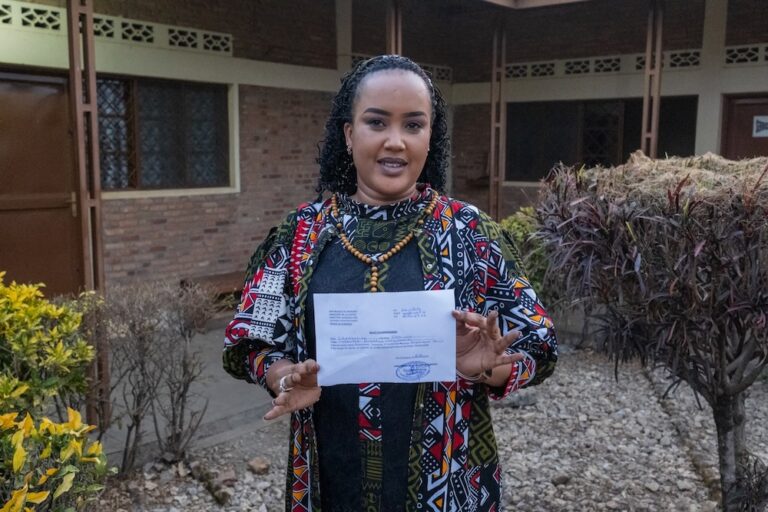

They include SOS Médias Burundi, which is celebrating the third anniversary of its creation this week. It has survived harassment and violence thanks to a network of anonymous reporters who work independently and use smartphones to send their stories. Its Facebook page, which now has more than 47,000 followers, is one of the few sources of credible and verified news reports from within the country.

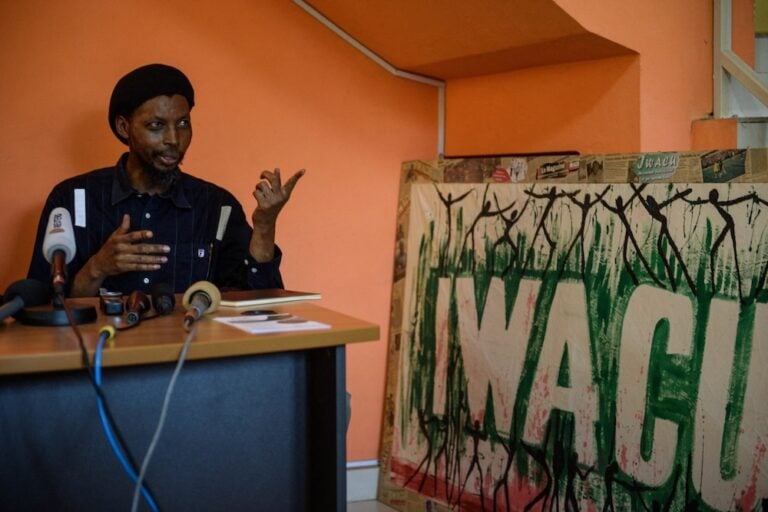

They also include the online weekly newspaper Iwacu, whose website has been “mirrored” as part of RSF’s Collateral Freedom operation since 12 March, World Day Against Cyber-Censorship. The original website has been inaccessible within Burundi since October 2017.

Iwacu reporter Jean Bigirimana has been missing since July 2016. Several witnesses said they saw him being arrested by members of the National Intelligence Service (SNR). The authorities have never said anything about his disappearance.

Burundi continues to languish in the bottom sixth of the RSF’s World Press Freedom Index, and is ranked 159th out of 180 countries in the 2018 Index.