While Cambodia has accepted the majority of the UN member states’ recommendations, questions remain about the country’s commitment to fostering a free and enabling environment for civil society and the media.

The Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC) has accepted 173 out of 198 recommendations made by 73 member states of the United Nations during the country’s third Universal Periodic Review (UPR). Cambodia’s report was discussed in January 2019, and the recommendations were officially adopted by the UN Human Rights Council this week, in Geneva.

(Read this IFEX explainer to learn more about the UPR process)

The 173 accepted recommendations focus on a wide range of important human rights issues in Cambodia, including ensuring protection of the rights of vulnerable groups, addressing the issue of discrimination against women, rule of law and fair trial rights, and the protection of human rights defenders, journalists, and members of civil society.

Civil society groups welcomed the decision of Cambodia to accept the majority of the recommendations.

Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR), noted that “It is very encouraging that Cambodia accepted all the recommendations related to the protection of SOGIE rights, which include amending the Constitution to allow for marriage equality for same-sex couples, enacting laws and policies explicitly prohibiting discrimination on the basis of SOGIE, and enabling legal gender recognition.”

The country’s commitment to fulfilling its international treaty obligations has been called into question. Since its second UPR, in 2014, when it accepted 162 of 205 proposed recommendations, Cambodia has enacted legislation that excessively restricts fundamental freedoms, and misapplied laws to undermine civil society, leaving civic space severely curtailed, as documented in our joint civil society submission to the UPR.

Cambodia’s third UPR took place six months after a landslide victory by the ruling party – a victory which followed the dissolution of the main opposition party Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) and the arrest of its senior leader, allegedly for conspiring with foreign powers to remove the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen. In recent months, at least 140 members and supporters of the former opposition party were summoned and detained by the police in what civil society groups have described as a clear form of judicial harassment.

So it is perhaps not surprising that the release of senior opposition leader Kem Sokha and the reinstatement of CNRP were among the recommendations ‘noted’ rather than accepted by the government.

“We cannot accept them and we cannot implement them because they go against Cambodia’s laws and violate Supreme Court rulings,” the government told the media. “[T]here are no political prisoners [in Cambodia], but only politicians who committed criminal acts in violation of the Criminal Code.” It added that charging Kem Sokha and other opposition leaders who committed “treason” is the “only legitimate way to protect peace and democracy under the rule of law”.

A paradise?

The government also ‘noted’ certain recommendations related to the Law on Associations and Non-Governmental Organizations (LANGO). It explained that LANGO was formulated in conformity with the provisions of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Nevertheless, it accepted other recommendations that included amending the LANGO and the Trade Union Law.

The government described Cambodia as a ‘paradise for non-governmental organizations’, by citing the high number of registered local and international associations in the country.

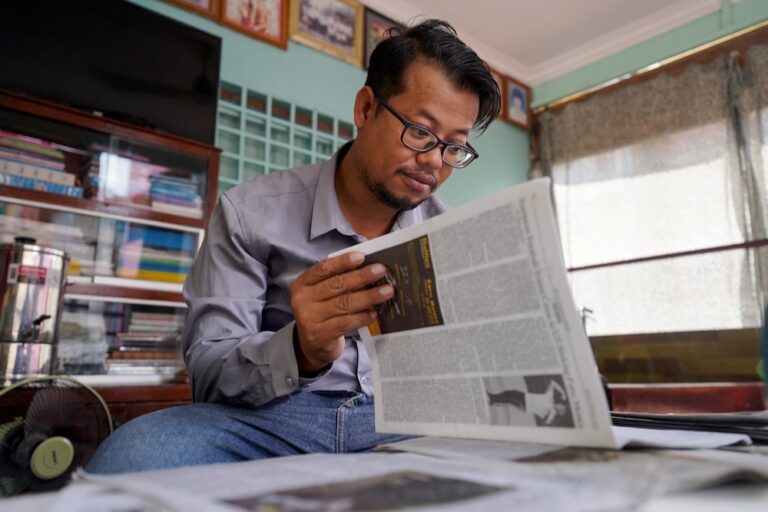

Sophal Sek, communications officer of Cambodian Center for Independent Media (CCIM), suggests that the government should be reminded that the number of registered NGOs “does not necessarily reflect the reality and quality of democracy, human rights and media freedom” in the country. “Let’s not ask how many NGOs we have, but ask how many NGOs are actively working without fear and intimidation? Very few.”

With respect to media freedom, the 5 April Report of the Working Group on the UPR mentioned that “no journalist had been killed for political reasons since 2000.” It said that imprisonment as a penalty for defamation was already removed from the Criminal Code, and provided a guarantee that no individual would be imprisoned for expressing his or her opinion. “The media are free to publish without advance censorship or restriction from the government. However, like every other citizen, journalists shall be responsible under the laws if they commit any illegal acts,” the report indicated.

In a conversation I had with Rohit Mahajan, spokesperson for Radio Free Asia (RFA), he recalled how “authorities prosecuted two former RFA reporters on false charges of espionage” and how this “prompted others to flee the country as they feared for the safety of themselves and their families.” He urged the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to remember its December 2018 statement about the government’s commitment to improve the democratic space in the country and the promotion of freedom of the press and freedom of expression.

“Human rights should not be politicized”

Asserting that “human rights should not be politicized” in the UPR, the government stated that the latter “is not a forum for political propaganda benefiting one group or one political party at the expense of others.”

Prime Minister Hun Sen reiterated this during his speech at the Human Rights Council on 4 July. He also criticized other countries for using ‘human rights as a hostage’ in trying to undermine his government.

“We are deeply sad to learn that human rights have been used nowadays by some powerful countries as a political tool, or as a new operational norm or an excuse for them to interfere in weaker states with sovereignty, full independence and territorial integrity.”

Nevertheless, he said Cambodia “remains committed to strengthening close cooperation and constructive partnership” with the UN and other stakeholders in promoting human rights.

Civil society appeals

CIVICUS, CCHR, Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC) and IFEX delivered a statement at the Human Rights Council’s session, urging the government “to take proactive and immediate measures to restore civic space, foster a free and enabling environment for civil society, and ensure that all Cambodians can freely exercise their fundamental freedoms.”

According to Sopheap Chak of CCHR, the government could still take certain measures to implement some of the recommendations that were noted, rather than accepted.

“It is disheartening that the government decided to note certain recommendations regarding the amendment of laws which currently excessively restrict fundamental freedoms, and some recommendations regarding media freedoms. Although these UPR recommendations are noted, we nevertheless encourage the RGC to seriously consider them. They could still take certain steps to implement some of them in order to meaningfully restore civic space, uphold respect for fundamental freedoms and overall improve the human rights situation in the country.”