(RSF/IFEX) – The following is an abridged version of a 27 September 2006 RSF press release: Spectre of Martin O’Hagan’s unsolved murder refuses to fade as press freedom takes a back seat on the road to peace On the eve of the fifth anniversary of the investigative journalist’s murder, Reporters Without Borders expresses its concern […]

(RSF/IFEX) – The following is an abridged version of a 27 September 2006 RSF press release:

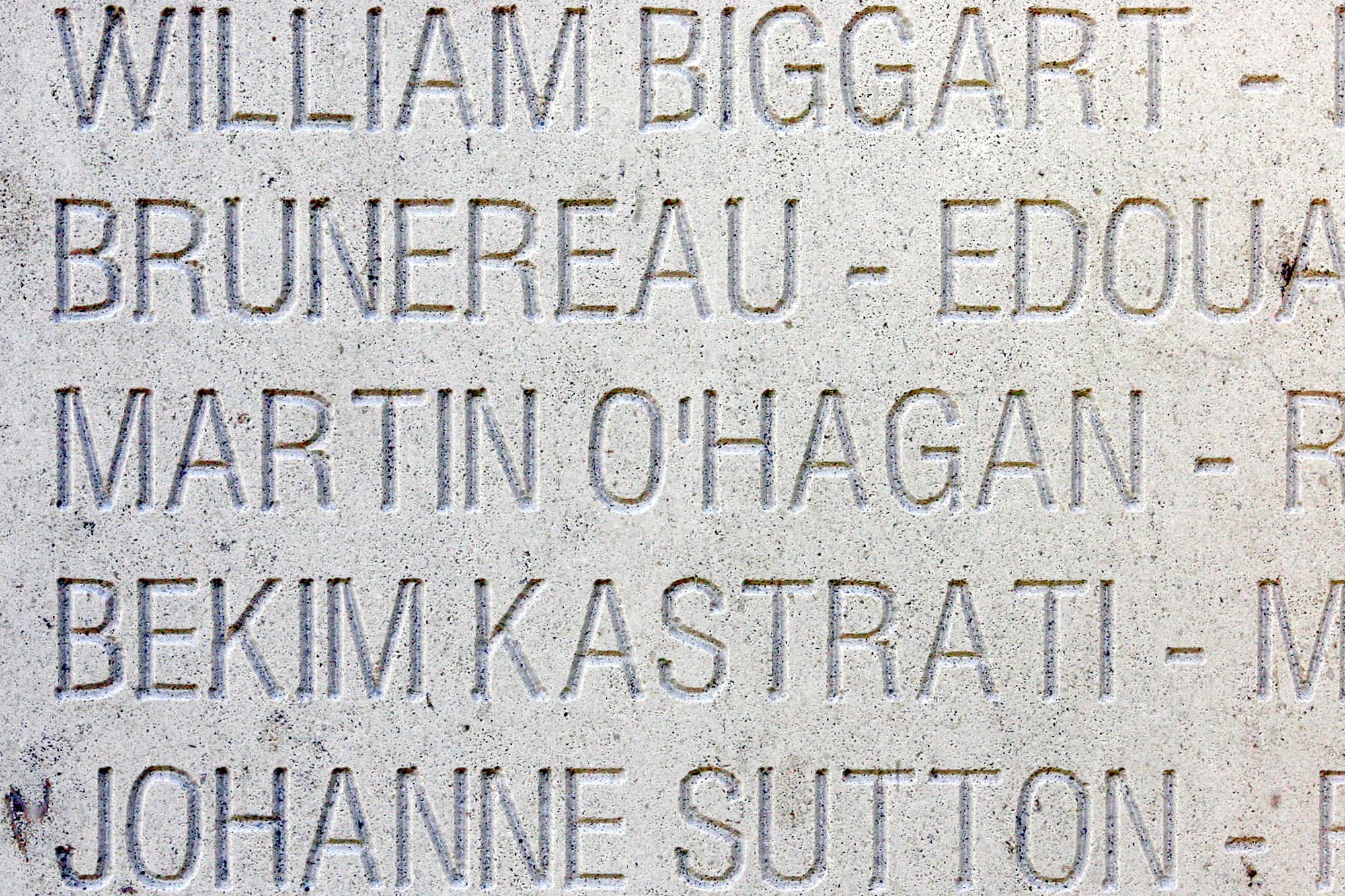

Spectre of Martin O’Hagan’s unsolved murder refuses to fade as press freedom takes a back seat on the road to peace

On the eve of the fifth anniversary of the investigative journalist’s murder, Reporters Without Borders expresses its concern about threats to press freedom in the peace building process in Northern Ireland. RWB’s UK correspondent, Glyn Roberts reports.

Five years after the investigative reporter, Martin O’Hagan, was shot dead outside his home, journalists in Northern Ireland have one simple question to ask police officers who have failed to bring anyone to justice: “Why?”

Why, they demand to know, has no one been prosecuted, despite the publication of considerable evidence pointing to a loyalist paramilitary gang operating near O’Hagan’s home in Lurgan, County Armagh? And why has the investigation failed despite the “absolute determination” of senior government and police officials at the time of the murder to catch the killers?

These questions will be delivered to the police by O’Hagan’s branch of the National Union of Journalists (NUJ) this week to mark the fifth anniversary of the drive-by shooting on September 28, 2001. A year ago, O’Hagan’s colleagues called for the investigation to be handed over to another police force. This has not happened. Many people now feel that the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) should itself be investigated for its failure to solve a murder that shocked the region – as O’Hagan was the first reporter killed during almost 40 years of strife there. There have been repeated allegations that the police failed to pursue inquiries with vigour for fear of exposing informers or agents within the murder gang.

Belfast and District NUJ branch officials will also hand a copy of their protest letter to the region’s police ombudsman, Nuala O’Loan, to draw her attention to their concerns. The ombudsman is empowered to hold independent investigations into clams of police misconduct and corruption. A report on one such inquiry will soon be published. No formal complaint has yet been lodged with Ms O’Loan regarding the O’Hagan murder, but his former colleagues say this is an option that could be pursued should the case remain stalled.

O’Hagan, 51, a father of three, was gunned down as he walked home from a pub with his wife, Marie. He was a short, cheerful man – known by his friends as “Marty” and the “wee man”. He was not short on courage, however, when reporting on the murky world of criminal fiefdoms, rooted in the long sectarian conflict, and on allegations of police collusion with paramilitaries.

His killers’ apparent impunity has not fostered press freedom in the region. Despite the peace process and IRA ceasefire of recent years, death threats continue to be made by shadowy groups against investigative journalists. At the time of the murder, perhaps three journalists were said to be working under death threat. That figure more than quadrupled in the following years, and all threats must now be treated deadly seriously.

Only last month, another reporter on O’Hagan’s newspaper, the Sunday World, was informed by police of a paramilitary threat against him and advised to take extra security measures. He had been inquiring into an unsolved murder linked to one of the loyalist gangs.

“I call them the para-mafia,” said Jim McDowell, 57, editor of the Northern Ireland edition of the Sunday World, one of two newspaper groups working under a general threat. “We’ve had several warnings over the past year or so. We regularly run stories exposing criminal activities and we’ve upset militants on both sides – republicans and loyalists. I’ve had 11 threats over the years, I think. My house is like a police station, with all the security devices.”

His office is similarly protected following past arson and bomb attacks. Last year, one loyalist gang – angry at the paper’s reporting – set out to intimidate newsagents stocking the Sunday World. “In one case, petrol was poured on bundles of papers, causing a fire that nearly killed two people in the shop,” he said. Sunday World staff have called for more effective police action to prevent such threats and violence, but McDowell says there is no question of self-censorship on his paper. “Martin O’Hagan never gave up and neither will we,” he said. They were determined to continue challenging the gangs. Eight years after the Good Friday peace agreement, their readers wanted to shake off the region’s violent past.

However, other journalists say that, despite the peace process, self-censorship remains a real threat. “The problems are as bad now or even worse since Marty’s death,” said Jim Campbell, who founded the northern edition of the Sunday World and who now writes a column for it. “Some reporters think to themselves, ‘Is this going to alienate someone?’ before they write an article.” Campbell, 63, who was once shot and seriously wounded for his reporting, points to subtler forms of pressure fuelling self-censorship. “Some reporters feel they have good police contacts or contacts with government officials and don’t want to jeopardise them,” he said.

There have been reports of a growing sense of antipathy among certain politicians and establishment figures – and even in the mainstream press – towards people branded “Journalists Against the Peace Process” (JAPPs). These are reporters who seek to unearth inconvenient truths that may be unpalatable to leading figures of the peace process. Even government officials have been heard referring pejoratively to certain journalists in such terms. One man who says he was called a JAPP for asking awkward questions is Ed Moloney, an award-winning Irish journalist and author, now based in New York. He recently accused certain media colleagues of wilfully turning a blind eye to IRA ceasefire breaches and of covering up the truth to “protect” the peace process.

Kevin Cooper, chairman of Belfast NUJ branch, of which O’Hagan was secretary, defends those who rock the boat. He said: “Genuine truth is not based on misconceptions. It is achieved through eyes wide open – not eyes wide shut.”

Sanctions against JAPPs can range from a petty lack of co-operation from officials to violent threats from thugs. “There are powerful vested interests that don’t want certain information dug out,” explained Cooper. “They would rather their past roles were kept secret.”

To read the full report, visit: http://www.rsf.org/article.php3?id_article=19011