Civil society groups said the continued investigation points to the "complete lack of evidence in support of the baseless charges" filed against the two Cambodian journalists.

This statement was originally published on cchrcambodia.org on 4 October 2019.

We, the undersigned civil society organizations strongly condemn the decision by the Municipal Court judge to continue the investigation into unsubstantiated espionage charges against Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin. The pair were arbitrarily arrested, detained and charged for the peaceful exercise of their freedom of expression and for their work as investigative journalists on issues of social justice. Yesterday’s hearing showed that there is a complete lack of evidence in support of these baseless charges exposing fair trial rights violations and highlighting the trial as a blatant affront to freedom of expression and media freedom in Cambodia. We urge the authorities to immediately drop all charges against the pair.

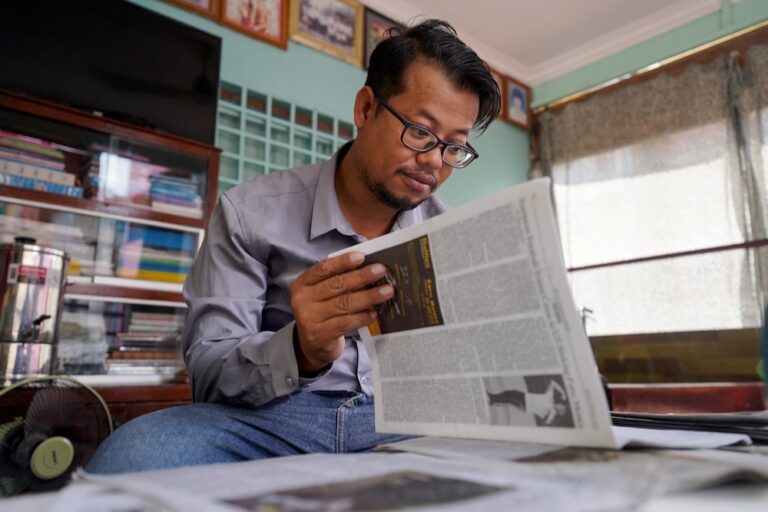

Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin, former Radio Free Asia (RFA) journalists, were arrested on 14 November 2017 and detained in Prey Sar prison. They were provisionally charged four days later with ‘supplying a foreign state with information prejudicial to national defence’, under Article 445 of Cambodia’s Criminal Code. The pair – who worked for RFA’s, now closed, Cambodia bureau – were denied their first bail application on appeal before the Supreme Court on 16 March 2018 and soon afterwards were charged by the Phnom Penh Municipal Court with the alleged production of pornography under Article 39 of the Law on the Suppression of Human Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation. As a result of the accumulated charges, each face 16 years in prison. On 21 August 2018 they were both released from Prey Sar prison on bail, after more than nine months in pre-trial detention, however they remain under judicial supervision.

The original verdict hearing was scheduled for 30 August 2019 but on the morning of the hearing it was delayed due to an unannounced absence of the judge. It was subsequently scheduled for 3 October 2019, however the Phnom Penh Municipal Court Court again failed to deliver a verdict on the grounds that further investigation was required. The failure to reach a verdict is indicative of a lack of credible evidence against the pair and as such illustrates that there is insufficient evidence to hold them criminally liable as per the burden of proof standards enshrined in Article 38 of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Cambodia (Constitution). Throughout the process of their arrest, detention, and ongoing trial, Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin have been denied the rights to fair trial, liberty and security protected under domestic and international human rights law.

Article 9(1) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), incorporated into domestic law by the Constitution, states that ‘no one shall be deprived of his liberty except on such grounds and in accordance with such procedures as are established by law.’ Article 14 thereafter preserves the rights to ‘be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law’ and to presumption of innocence. The charges levelled against Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin are unsubstantiated and lack a clear legal basis. Instead, they have been employed as a means to punish the legitimate exercise of the right to freedom of expression and silence journalism critical of the government. The pair had previously reported on a wide range of

human rights issues.

In addition to baseless charges, the holding of these two men in pre-trial detention in deplorable conditions for more than nine months, and their continued placement under judicial supervision of already 12 months, violates their right to liberty and to a fair trial guaranteed under international law and the Constitution. International law stipulates that people charged with criminal offenses should not, as a general rule, be held in custody pending trial – a requirement not adhered to in Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin’s case.

In May 2019, the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention issued an opinion on the case, finding that the Cambodian government had failed to (1) establish a legal basis for arrest and detention, and (2) provide proof that it had considered alternatives to pre-trial detention. Concluding that the pre-trial detention of the journalists resulted from their peaceful exercise of the right to freedom of association and the freedom of expression, the Working Group found their deprivation of liberty to be arbitrary.

The prosecution of Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin is but one piece of the broader legal assault on journalists, human rights defenders, members of the political opposition, union leaders, activists, civil society representatives and individuals expressing their views on matters of public interest, including expressions of critical dissent. While the situation of press freedom was already constricted prior to 2017, since then Cambodia has seen almost all of its independent and local media silenced. Critical Khmer-language media outlets have had their activities severely restricted, including via the closure of 32 radio stations relaying RFA, Voice of America (VOA) and Voice of Democracy (VOD). RFA closed its Cambodia bureau in September 2017, citing the repressive environment and ongoing harassment of their journalists. The change of ownership of the Phnom Penh Post in May 2018, Cambodia’s last remaining independent English-Khmer language daily, was widely regarded as the last blow to press freedom in Cambodia. The space for freedom of expression online is also severely curtailed, illustrated through the increase in harassment of individuals who merely peacefully dissent or express their opinions through shares, posts or likes on Facebook.

The right to freedom of expression, protected by Article 19 of the ICCPR and Article 41 of the Constitution, is essential for the guarantee of the exercise of all human rights, including the rights to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, freedom of information, and the right to develop one’s personality and private life. As such, the importance of creating an enabling environment in which journalists are free to conduct their work – including by exposing corruption, expressing diverse viewpoints and shedding light on human rights violations – cannot be understated.

The failure to vacate the charges against Yeang Sothearin and Uon Chhin strikes yet another blow against what little remains of freedom of expression and media freedom in Cambodia. This case sends a clear warning to individuals who dare to exercise their fundamental right to freedom of expression and fosters an environment of intimidation and censorship. The legitimate and invaluable work of these individuals should be recognized, in line with Cambodia’s human rights obligations, and they should be able to carry out their activities in the future without fear of reprisal, obstruction or threat of prosecution. We encourage the Royal Government of Cambodia to cease its intimidation and harassment of all individuals exercising their right to freedom of expression and to re-establish an enabling environment for a free and pluralistic media and a thriving civil society in line with its obligations under the Constitution and international human rights law.

– END –

This joint statement is endorsed by:

1. Alliance for Conflict Transformation (ACT)

2. Amnesty International

3. Article 19

4. ASEAN Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR)

5. Asian Forum for Human Rights and Development (FORUM-ASIA)

6. Asian Network for Free Elections (ANFREL)

7. CamAsean Youth’s Future (CamASEAN)

8. Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR)

9. Cambodian Center for Independent Media (CCIM)

10. Cambodian Food And Service Workers Federation (CFSWF)

11. Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC)

12. Cambodian Independent Teachers’ Association (CITA)

13. Cambodian Volunteers for Society (CVS)

14. Cambodian Youth Network (CYN)

15. Coalition for Integrity & Social Accountability (CISA)

16. Committee for Free and Fair Elections in Cambodia (COMFREL)

17. Community Legal Education Center (CLEC)

18. Center for Alliance of Labor and Human Rights (CENTRAL)

19. CIVICUS: World Alliance for Citizen Participation

20. Human Rights Watch (HRW)

21. Independent Democracy of Informal Economy Association (IDEA)

22. Independent Trade Union Federation

23. Indradevi Association (IDA)

24. International Commission of Jurists (ICJ)

25. International Freedom of Expression Exchange (IFEX)

26. Khmer Kampuchea Krom for Human Rights and Development Association (KKKHRDA)

27. Klahaan

28. Labor Rights Supported Union of Khmer Employees of Naga World (L.R.S.U)

29. Minority Rights Organization (MIRO)

30. People Center for Development and Peace (PDP-Center)

31. Ponlok Khmer (PKH)

32. Reporters Without Borders (RSF)

33. Sahmakum Teang Tnaut (STT)

34. Urban Poor Women Development (UPWD)

35. World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT)

36. Youth Education for Development and Peace (YEDP)

37. Youth Resource Development Program (YRDP)