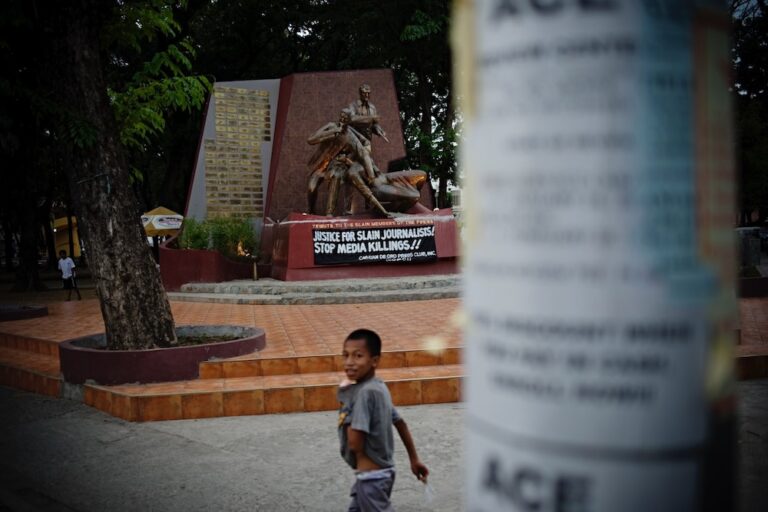

The 2009 Ampatuan massacre of 58 men and women, including 32 journalists, was a reminder and a warning to both the Philippine press and the entire country, CMFR notes.

(CMFR/IFEX) – 23 November 2010 – The 2009 Ampatuan Massacre of 58 men and women including 32 journalists was a reminder and a warning to both the Philippine press and the entire country.

The Philippines is officially a democracy, but the pockets of warlord power that have been allowed to flourish in at least a hundred localities mock that claim. In places like Maguindanao, private armies decide elections and also wield the power of life or death over the men and women under warlord rule.

In those places, the Massacre also demonstrated, the power of the written and spoken word that many assume protect journalists and media workers is already meaningless. The 32 journalists and media workers killed who had accompanied the wife and kin of the then candidate for Maguindanao governor in filing his certificate of candidacy were supposed to protect the group, despite the fact that before the massacre, 81 journalists had been killed in the line of duty since 1986.

Although the worst incident of violence against journalists, the Ampatuan Massacre occurred in the context of the culture of impunity that has persisted in the Philippines. That culture has allowed and encouraged not only the killing of journalists, but also of political activists, judges, lawyers, human rights workers and other citizens. While officially at peace, the killing of journalists and media workers, and of over a thousand others killed extrajudicially, has also made many localities virtual war zones.

The new Aquino administration has the opportunity – by increasing the budget for witness protection, improving police efficiency, and enhancing the prosecutorial capacity of the Department of Justice, among others – to help end impunity.

The state failure to address the killing of journalists, and state involvement in extra judicial killings (EJKs), have made the culture of impunity the biggest threat to free expression and democracy in the Philippines. The dismantling of that culture, CMFR has pointed out many times, is predicated on punishing the killers and masterminds in the killings, whether that of journalists or of political activists.

The sheer number of journalists killed in the Ampatuan Massacre, and the perils of warlord rule it demonstrated, have made the apprehension, trial and punishment of the killers and masterminds especially crucial. If its perpetrators are not punished, not only will it prove once more that warlord rule cannot be uprooted; it will also be the strongest signal yet that anyone may kill journalists and activists with impunity.

And yet the progress of the trial of those accused of planning and carrying out the Ampatuan Massacre has been agonizingly slow, once more demonstrating that the complexities of the legal system meant to protect the innocent have been effectively functioning on behalf of murderers and other criminals. Many of the rules governing court proceedings, it has also been pointed out, were put in place 50 years ago and need to be amended, or thrown out all together. Under existing conditions, the trial of the accused could take a decade or more.

These conditions impose on the press the responsibility of keeping the Massacre and the trial of those accused of it in the public mind. But both the media and the citizenry must also seek and support amendments to the rules of court proposed by progressive lawyers so as to accelerate the judicial processes for the sake of that goal, so elusive in this country, of justice.