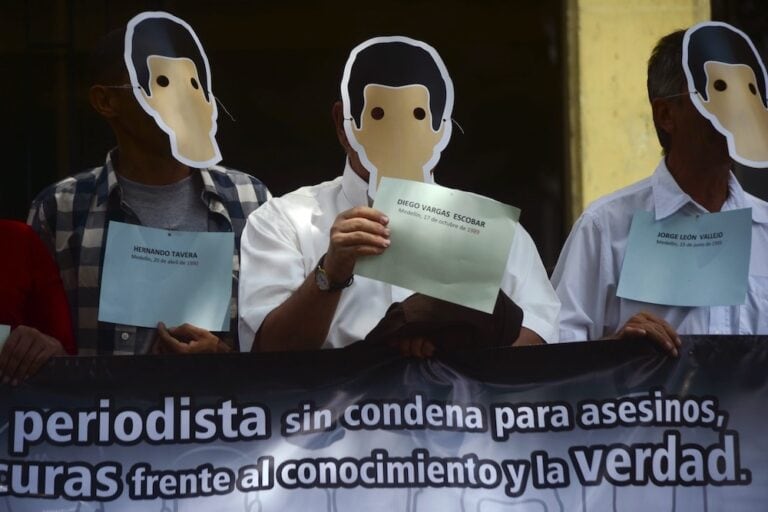

Communicators from across the country said they occupy a particularly precarious place in Colombia’s press corps as threats to their reporting and safety come from many sides.

This statement was originally published on cpj.org on 26 May 2022.

Mabel Quinto Salas is a reporter for Radio Pa’yumat, a station in the Northern Cauca region of Colombia. But she doesn’t identify as a journalist. Instead, she calls herself a “community communicator,” a category that is common among Colombia’s Indigenous communities.

“Communication is seen as a tool for visibility, for denunciation of human rights violations, but also for community and territorial defense,” Quinto, a member of the Nasa community in Colombia’s Çxhab Sala Kiwe Indigenous territory, told CPJ.

Communicators report on their own communities and the subjects that impact their lives, such as forced displacement due to land disputes between the government and multinational corporations, the climate crisis, and other issues. They say that their proximity to the people and issues they cover make them better at telling the community’s stories and relaying critical information to their audiences.

However, they say they face special challenges in their work. In interviews with CPJ, communicators from across the country said they occupy a particularly precarious place in Colombia’s press corps as threats to their reporting and safety come from many sides, including state security forces and non-state armed actors. Beyond physical violence, many say they face discrimination and attempts to discredit their work by both the non-Indigenous public and law enforcement.

Many communicators report for radio stations affiliated with Colombia’s Indigenous councils, and some are council members, blurring the line between journalist and authority that exists in many parts of the world. Quinto, for example, is a member of the Regional Indigenous Council of Cauca, or CRIC, an umbrella group promoting Indigenous self-governance.

But that blurring is part of the point as communicators see themselves as standing up for their rights, just as the councils do. “Self-determined communication,” as Quinto calls her reporting, fulfills a need that Colombia’s other media – whether state and military-run, private, or independent – has been unable or unwilling to fulfill, she said.

In the Pacific coast city of Buenaventura, Colombia’s busiest port, freelance documentary photographer and communicator, Jann Hurtado reports on the experiences and everyday life of the city’s predominantly Afro-Colombian residents. Hurtado told CPJ that the risks facing communicators are intensified at protests as law enforcement, which has a ruthless history of suppressing protests, sometimes confuse them with protesters.

“Many of my colleagues – documentary photographers or freelance photographers – are scared to go out and cover protests or events because we don’t know if we’ll be able to return to our homes… with our equipment and team intact,” said Hurtado.

Diana Mery Jembuel Morales, an Afro-Indigenous Misak communicator, told CPJ that authorities at protests don’t recognize communicators as legitimate journalists.

“When you attend a large protest and see a journalist with a [press] vest, the state authorities respect their presence… but when you see a communicator with a tape recorder or camera, they do not respect them,” said Jembuel, who is also a former leader of an Indigenous council.

Javier Mauricio García Jiménez, who in 2015 founded Teleafro, a Bogotá-based TV news channel produced by Afro-Colombians, agreed. “Although [the police] don’t touch you, you feel like at any moment a bullet could come at you and not only damage your camera but your head as well, so naturally you limit yourself in many street protests.”

CPJ emailed questions about police behavior toward journalists at protests to the office of the Colombian ministry of defense but did not receive answers.

Another issue facing communicators is lack of access. Jembuel described incidents in which officials never returned requests for information on territorial disputes or forced displacement, or were slow to do so. “We must be careful about who we interview, how we interview them, and why we are interviewing them, because many institutions refuse to give us any information at all,” she said.

Other communicators said authorities give preferential treatment to mainstream outlets. Afro-Indigenous communicator and Indigenous council member Erika Yuliana Giraldo Zamora from the Embera Chamí community in the Caldas department in Colombia’s central coffee region, said local communicators struggle to get interviews with state officials. On the other hand, she has seen reporters from Bogotá-based outlets like national television network RCN fly in police helicopters as part of their coverage.

Juan Pablo Madrid-Malo Bohórquez, a coordinator at the Bogotá-based Foundation for Press Freedom, or FLIP, told CPJ that during the 2019 military Operation Artemis, which has allegedly displaced people in the name of fighting deforestation, reporters from national outlets were accompanied to the site of the operation in police helicopters while communicators had to rely on WhatsApp communiques from the authorities.

While the communicators are not formally recognized as journalists, they still attract similarly unwanted attention from the authorities. CPJ has documented a long history of surveillance of journalists and other public figures by Colombian military and intelligence authorities, from a wiretapping scandal that led to the dissolution of the national intelligence agency in 2011, to revelations in 2020 that members of the military had illegally surveilled investigative journalists working for national newsweekly Semana.

Jembuel believes she and her colleagues have been among those monitored, recounting times that she and her colleagues detected interference on phone calls, or received anonymous calls from people seeking information about Indigenous activities. She said that she has mysteriously lost internet service, alleging that it was a way for authorities to silence her work.

CPJ emailed questions to the office of the Colombian Ministry of Defense and received confirmation of our inquiry but did not receive a response regarding the possibility of phone monitoring.

On top of these other obstacles, Colombia’s Indigenous communicators confront the constant barrier of discrimination. “It’s harder, because there is so much racism,” said Giraldo, “Apart from the fact that you are an independent, alternative communicator, you are also Indigenous.”

Laura Rodriguez is a former CPJ intern and an associate project manager at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston. She is an alumna of Northeastern University where she earned a bachelor’s degree in international affairs and journalism and a masters degree in international affairs with a focus on public policy and Latin America.