A new illegal spying scandal in Colombia involving the National Police has brought about the resignation of the Chief of the National Police, set off an investigation by the country’s Inspector General and brought the issue of illegal surveillance by Colombian authorities back into the national discussion.

This statement was originally published on privacyinternational.org on 8 March 2016.

A new illegal spying scandal in Colombia involving the National Police has brought about the resignation of the Chief of the National Police, set off an investigation by the country’s Inspector General and brought the issue of illegal surveillance by Colombian authorities back into the national discussion.

With another institution engulfed in a spying scandal, it begs the question: just how many more of these can Colombia take before something finally changes?

Privacy International’s report from September 2015, “Shadow State: Surveillance, Law and Order in Colombia”, showed that these scandalised institutions were using several surveillance technologies that no one knew they had.

The new chuzada scandal

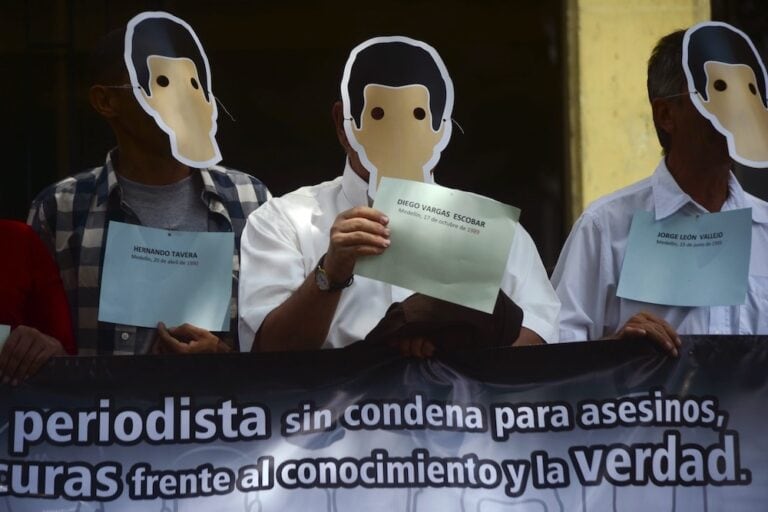

In early December 2015, journalists of the local radio station La FM received an anonymous tip that they were being surveilled by the National Police Directorate because of their investigation about alleged acts of corruption and sexual offences by top officials. This was quickly followed by Attorney General (Fiscal General de la Nación), Eduardo Montealegre announcing an investigation into national police corruption and sexual misconduct, as well as the surveillance and intimidation of journalists working on the story. On 9th December Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos announced a commission to investigate the claims.

The Government reacted quickly over the ensuing ten days, before its efforts screeched to a halt. Nearly two months passed with no news on the Commission. On 17th February, one day after Inspector General Alejandro Ordonez announced an investigation into the allegations against the head of the Police, General Rodolfo Palomino resigned as Chief of the National Police. He maintained his innocence, but to many observers, his tenure as the head of the country’s forces of order had become untenable.

On 17th February, the Colombian media reported that Inspector General Ordonez had requested from the Karisma Foundation – one of Privacy International’s partners in Colombia – a copy of Privacy International’s report Shadow State: Surveillance, Law and Order in Colombia to form part of the evidence for the investigation into the latest spying scandal. The report was submitted electronically and physically to the Inspector General’s office on 26th February.

What the Inspector General will see: DIPOL and the Integrated Recording System

The aspects of the report relating to the Directorate of Police Intelligence (DIPOL) should make for sobering reading for the Inspector General. The report reveals technologies purchased by DIPOL as far back as 2005. Our legal analysis suggests that DIPOL has no mandate to operate these technologies, which are capable of intercepting the same types if not more Colombians’ private communications data than the lawful, warrant-based interception system operated by the Attorney General’s office.

In 2005 DIPOL put out a call for tenders to provide equipment necessary to monitor 3G networks as part of an Integrated Recording System (IRS) – in Spanish, Sistema Integrado de Grabación Digital con destino a la Policía Nacional. This system was conceived to surpass the interception of pre-assigned targets and to automatically collect ‘massive’ communications traffic across 16 trunk communication lines. As DIPOL clarified to companies bidding to provide this ‘solution’, “the solution should include mass storage of traffic over all input E1 lines”.

The existence and procurement of this equipment should pique scepticism over the Police’s previous public statements concerning the nature of the communications surveillance infrastructure in Colombia.

The Government has consistently maintained that the surveillance system developed in the late 1990s and early 2000s known as Esperanza, administered by the Attorney General’s office, was the only method through which interceptions could take place legally and technically. In the past, police officials from the Police Directorate of Criminal Investigation and Interpol (DIJIN), have said exactly that: “We are subordinated to the administrative control of the Fiscalía (Attorney General’s) office…Nothing is activated if not technically authorised by Esperanza.”

If Esperanza was the only route through which surveillance could be operated technically and legally, why did DIPOL respond to questions about the IRS system’s connection to Esperanza that “In no place are we talking about applying this development to the Esperanza system”? And when asked again about the new system’s connections to the Attorney General’s warrant-based interception system: “No, they [the probes] don’t come from the Esperanza switch”?

In addition to the Integrated Recording System, there are suggestions that other types of surveillance technologies had been used to track and suppress the La FM investigation. According to a journalist working on the La FM story, his cursor had moved without him touching it while he was working with sensitive documents.

While this report in no way conclusively proves of the existence of hacking tools in Colombia, reports from Citizen Lab and information revealed in a leak of documents relating to Italian company Hacking Team suggest that their product ‘Remote Control System’ had been sold to Colombia. The description of a mouse cursor moving is highly unorthodox for operating intrusion software, but it is possible that Hacking Team equipment enables this, throwing another question into the mix about the use of hacking tools and how to effectively oversee the use of such clandestine technologies.

Unregulated surveillance

The procurement and purchase of these technologies by DIPOL should be enough to cause the President, the Commission, and the Attorney General concern. Based on Privacy International’s analysis of the available legislation to date in Colombia, DIPOL have no legal mandate to conduct what amount to mass interception of communications data surveillance.

The Attorney General’s office is the only body that can lawfully undertake interception of communications of this type in Colombia, pursuant to a court order authorised by a judge, following procedures established in laws contained in the Criminal Procedure Code. Why is it that DIPOL had access to surveillance technologies that had no connection to the Esperanza system and thus apparently no direct oversight from the Attorney General’s office? DIPOL – as an agency with a mandate to collect intelligence, rather than investigate for prosecution, has some ability to carry out surveillance activities, but these are limited. The powers they have granted themselves by acquiring such surveillance technologies far outstrip this mandate.

Time for some answers

In the recommendations of Shadow State, Privacy International and Karisma called for the Inspector General to investigate whether DIPOL had been operating outside its legal mandate by procuring, purchasing and deploying surveillance technologies. Those questions still remain and need to be answered.

The myriad responses from different offices in Colombia have come too late to prevent another scandal unfolding and further harm being done to the trust in the security services in Colombia. There are deep, wide ranging questions to be asked which may bring uncomfortable conclusions. But these are necessary.

This cannot be about merely changing the personnel in charge of the National Police. There must be a fundamental reconstruction of the practices of the agency, the oversight of those practices, and the laws underpinning the whole system. Only then can this new scandal begin to be properly dealt with, which is the very least Colombia deserves.