March 2020 in Asia-Pacific: A round up of key free expression news, based on IFEX member reports and news from the region.

What we saw spreading quickly across the region in March was not just the dreaded coronavirus, but the mainstreaming of laws, regulations, and other emergency measures deemed essential in fighting it. These measures are also – perhaps not coincidentally – very useful in suppressing critical voices. In short, the fear, disruption, and confusion caused by the pandemic are enabling various governments to attack freedom of expression in the name of addressing a public health crisis.

How China censored reports on coronavirus

China’s censorship machinery has been systematically deployed to control narratives about the spread of COVID-19. Its strategy to contain the virus has included a sustained campaign to mute whistleblowers, monitor and censor conversations in messaging apps, and aggressively promote the government’s supposed success against COVID-19.

Freedom House has extensively reviewed the propaganda tactics of the Beijing government and the surveillance tools it used to censor online content about the virus. It also raised the concerns of other media groups about the alarming disappearance of citizen journalists and other ‘information heroes’ who reported the conditions in Wuhan and people’s critical perspectives about the government’s response to the virus outbreak.

Meanwhile, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) interviewed Citizen Lab researcher Lotus Ruan, who was part of a team that investigated China’s censorship of certain keywords on social media and messaging platforms. The researcher noted that the strict control of reports about COVID-19 prevented people from sharing information vital to family and friends: “Broad censorship of neutral and even factual information related to the virus might have limited the public’s ability to share and discuss knowledge of the prevention of the disease.”

Kashmir: Living in the time of COVID-19 and an internet blackout

Internet remains largely restricted in Kashmir seven months after Article 370 of the Indian Constitution – which used to guarantee the region’s autonomy status – was revoked .

Despite the Supreme Court ruling in January 2020 which invalidated the indefinite internet shutdown orders of the government, Kashmir has been limited to the use of 2G services, which basically allows only an exchange of text messages.

This has prevented eight million Kashmiri residents from accessing reliable health information about COVID-19. The devastating potential impact cannot be overstated. Media cannot properly report about public health and medical services are disrupted, including the delivery of other basic services that need online processing.

A petition is calling on the government to urgently restore internet networks in Kashmir.

Appeals for media protection

Journalists across the region are asking media owners and governments to provide greater protection for reporters and other workers we rely on to inform the public about the pandemic.

In Sri Lanka, six groups of journalists have issued a joint statement asking the owners of electronic and print media companies to ensure the protection of their workers, especially those involved in the distribution of newspapers.

In Indonesia, IFEX member the Alliance of Independent Journalists (AJI) reminded media companies “to develop safety guidelines and provide journalists with health products, such as hand sanitizers, to protect them while in the field and in their office.” AJI made the demand after it was reported that several officials who participated in press conferences had tested positive for COVID-19.

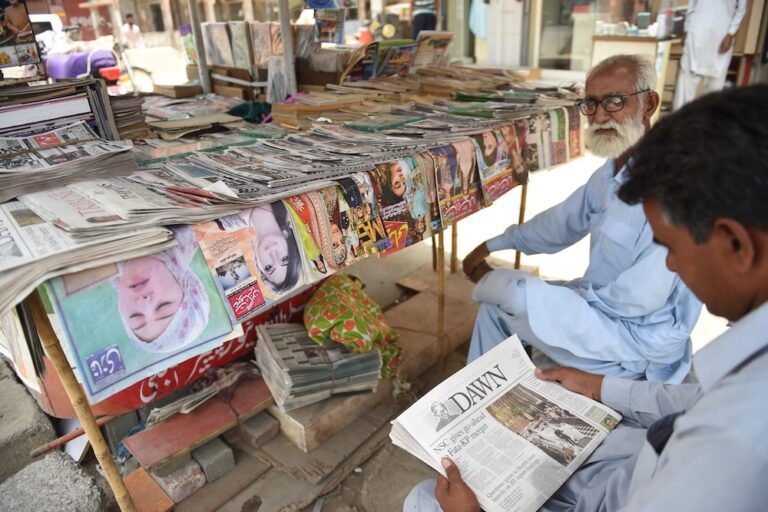

In Pakistan, TV journalists in Lahore were infected with the disease which they probably acquired during field reporting. Media executives were told to prioritize the health of reporters in drafting guidelines for COVID-19 coverage.

In China, the government is being urged to extend leniency to detained journalists by releasing them and preventing the spread of COVID-19 in prisons. According to Reporters Without Borders (RSF), there are at least 108 journalists, political commentators, bloggers and publishers who are currently languishing in jails and camps across the country.

In India, several journalists were harassed and attacked by the police while covering the impact of the government order placing the country under lockdown. Media groups have asked the government to probe the violence and allow reporters to perform their work without restrictions.

Australia: Support for regional papers and performing artists

In Australia, IFEX member the Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance (MEAA) has sent an appeal to the Australian Associated Press (AAP) about the decision of the latter to close operations after 85 years of operating in the country. MEAA said AAP should reconsider the closure, and instead continue its valuable service of providing the public with credible reporting as the country and the rest of the world struggle to defeat COVID-19.

MEAA has also asked the Federal government to unlock the allocation for the Regional and Small Publishers Jobs and Innovation Package and repurpose it into a survival fund to prevent local and regional publishers from closing their operations. MEAA said the closure of some regional newspapers led to job losses and is undermining the public’s right to accurate information about COVID-19 and other issues.

Meanwhile, the performing arts and screen sectors have been gravely affected by venue closures, show cancellations, and movement restrictions in response to COVID-19. MEAA has called for a wage subsidy and other forms of assistance to freelancers, self-employed contractors, and casual workers who lost their jobs, and, in light of income subsidies and business support announcements, calling on media houses to re-employ staff they had let go.

Some of those affected artists have organized a campaign to offer hope to fellow performers and to demand support from the government.

Others participated in a creative protest to save their jobs.

Philippines: Media accreditation and ‘fake news’ legislation

IFEX member the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) joined colleagues from the media sector in the Philippines in opposing a government accreditation process for journalists who wish to be exempted from the ‘enhanced community quarantine’ so that they can move around in order to do their work.

The joint statement of various media groups described the imposition as “unnecessary, unreasonable and unconstitutional.”

“What concerns us most is the possible misuse or abuse of accreditation to try and control the free flow of information, a concern rooted in this administration’s record of open hostility toward critical media.”

Indeed, some alternative media groups were refused accreditation; the government limited the number of special passes it issued in favour of select mainstream media groups.

Another worrying development is the passage of a law granting special powers to President Duterte in handling the COVID-19 pandemic. A provision was inserted in the bill criminalizing the publication of “false information” which human rights advocates criticized as a threat to free speech. They warned that “the law will leave it up to the government to be the arbiter of what is true or false, a prospect that cannot invite confidence given the fact that many administration officials, including the chief executive, have been sources of disinformation and misinformation.”

Thailand’s emergency decree gives unlimited powers to the government

Thailand’s prime minister has signed an emergency decree in response to the COVID-19 outbreak but human rights groups said it’s also being used to silence critics of the government.

It includes a ban on communications that are deemed by authorities to be “false” or “misleading”. It also prohibits “any kind of assembly and activity in a congested place or any kind of seditious act”. It empowers the government to order the closure of public venues, ban international visitors, and stop the hoarding of goods.

Based on local reports, at least 10 internet users have been charged in relation to social media posts about COVID-19, including a Phuket-based artist who was arrested for writing on Facebook that there was no thermal screening of passengers at Bangkok airport. Health workers were also censored for alleging corruption in the hoarding of surgical masks and for criticizing the government’s response to the pandemic.

Critics fear that the government will use the emergency decree to tighten its grip on power, threaten opposition forces, and instil fear among the local population.

Cambodia uses COVID-19 measures to attack opposition members

Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that 17 people have been arrested in Cambodia for sharing online information about COVID-19. Four of the 17 were members of the dissolved opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party.

Cambodia’s Information Ministry said it has identified 47 Facebook users and pages which have been spreading misinformation about COVID-19 “with the intention of causing fear in the country and damaging the government’s reputation.” The prime minister even reportedly compared those who post ‘fake news’ with terrorists.

HRW said authorities are “misusing the COVID-19 outbreak to lock up opposition activists and others expressing concern about the virus and the government’s response.”

Focus on gender: Pakistan’s Aurat March

Despite legal obstacles and violent threats, Aurat March (Women’s March) protest actions were held for the third straight year across Pakistan in time for International Women’s Day. The marches were successfully organized in Lahore, Karachi, Islamabad, Multan, Quetta, Peshawar and Sukkur which gathered thousands of women, LGBTQI+, and other members of the community who support gender equality and human rights. The peaceful march in Islamabad was violently challenged and attacked by conservative forces, but the women-led action in the city remained the biggest assembly in the country that day.