In the run up to elections, Ugandan authorities are honing in on regulations meant to curb COVID-19 and using them to restrict online digital rights.

This statement was originally published on cipesa.org on 15 December 2020.

The outbreak of coronavirus disease (Covid-19) could not have come at a worse time for Uganda, as the country prepares for what is being referred to as a “scientific election”, where physical rallies are severely restricted, with candidates advised to rely more on the media to canvass support.

Various measures adopted by the government to fight Covid-19 are hampering the enjoyment of various rights and freedoms, and the conduct of the election. The onslaught on the media, the political opposition and social media users has undermined citizens’ right to freely express themselves, and to access to a variety of news and information, which is critical to their informed decision making during this electoral process.

The right of individuals to peaceful assembly and association is linked to their ability to freely express their opinions, and to share and have access to information, both offline and online. However, in response to the pandemic, the government, adopted a series of statutory instruments which quickly suspended constitutional guarantees without reasonable justification or meaningful stakeholder consultation.

Uganda instituted the first set of measures to contain the spread of Covid-19 on March 18, 2020, which included the closure of schools and a ban on all political, religious and social gatherings. A week after the March 22, 2020 confirmation of the first case in the country, the ministry of health issued The Public Health (Control of COVID-19) (No. 2) Rules, 2020 that introduced further restrictions including a dusk-to-dawn curfew, the closure of institutions of learning and places of worship, the suspension of public gatherings, a ban on public transport and the closure of the country’s borders and international airport to passenger traffic.

Many of these measures, including the opening of the country’s international borders, easing of public transport, and allowing public gatherings of up to 200 people, have since been relaxed. However, in the run-up to the January 14, 2021 elections the state has continued to invoke the repressive Covid-19-related laws and regulations, as well as those predating the pandemic, as a tool to intimidate, arrest, and detain persons, including critics and political opponents. Consequently, it is increasingly looking like Covid-19 has handed the government a ready excuse to trample citizens’ digital rights and hinder civic engagement and mobilisation by its opponents.

The January elections will pit the incumbent president Yoweri Museveni, who is seeking to extend his 35-year rule, against 10 other candidates.

Curbing Freedom of Expression

Like many other countries, Uganda was hit by cases of Covid-19 related misinformation, and as early as February 2020, the Ministry of Health had moved to dispel reports that cases of Covid-19 had been confirmed in the country.

In March. the communication regulator, Uganda Communication Commission (UCC), issued a public advisory notice against individuals misusing digital platforms to publish, distribute and forward false, unverified, or misleading stories and reports. The regulator warned that any suspects would be prosecuted for offending the Computer Misuse Act 2011, the Data Protection and Privacy Act 2019 and Section 171 of the Penal Code Act Cap 120.

Also in March 2020, the UCC wrote to three media houses – BBS, NTV, and Spark TV – demanding that they show cause why regulatory sanctions should not be taken against them. The regulator accused the media houses of airing content that had the potential “to confuse, divert and mislead unsuspecting members of the public against complying with the guidelines issued by Government authorities on the coronavirus.”

In April 2020, Adam Obec of the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) was arrested on allegations of “spreading false information regarding coronavirus.” According to the police, Obec had circulated information on social media claiming that Uganda had recorded its first Covid-19 death, an action that had purportedly triggered fear and panic in the public and undermined government’s efforts to contain the pandemic.

In the same month, Pastor Augustine Yiga (now deceased) of Revival Church in Kampala was arrested and charged for uttering false information and spreading harmful propaganda in relation to Covid-19. He was later released on a non-cash bail pending trial.

On April 21, the Ugandan military arrested and detained Kakwenza Rukirabashaija, a writer, over an April 6 Facebook post that allegedly urged the public not to comply with Covid-19 public health guidelines. The post suggested that the president needed to “be serious” about enforcing directives, and that “if the country plunges into the abyss of famine … never blame Coronavirus but yourself and [your] bigoted methods.” The author was charged with committing an act likely to spread a disease, contrary to section 171 of the Penal Code Act and transferred to civil detention on remand. He was later released on a non-cash bail.

Increased Surveillance and Processing of Personal Data

The on-set of Covid-19 led to an increase in incidents of personal data collection and processing as the government traced suspected Covid-19 patients and their contacts. As part of efforts to Covid-19, the government passed various statutory instruments that can be interpreted to be the legal basis for contact tracing. These included the Public Health (Control of COVID-19) Rules, 2020 under the Public Health Act, which gave powers to a medical officer or a health inspector to enter any premises in order to search for any cases of Covid-19 or inquire whether there is or has been on the premises, any cases of Covid-19. Additionally, section 5 of the rules empowers the medical officer to order the quarantine or isolation of all contacts of the suspected Covid-19 patients.

Also introduced was the Public Health (Prevention of COVID-19) (Requirements and Conditions of Entry into Uganda) Order, 2020 that allows a medical officer to examine for Covid–19, any person arriving in Uganda. The medical officer may board any vehicle, aircraft or vessel arriving in Uganda and examine any person on board.

In the same month, the Ministry of Health also issued additional Guidelines on Quarantine of Individuals in the context of Covid-19 in Uganda, which required all quarantined persons to provide their name, physical address, and telephone contact to the healthy ministry monitoring team.

Earlier in March 2020, the government reportedly struggled to trace and contact returnees for testing and possible quarantine, as many of them had chosen not to present themselves to the authorities. However, the ministry of health said that it was in possession of the contact details of all returnees, which it was using to trace them.

However, in what appears to be a breach of individual privacy, there were reports of some Ugandans using online platforms, mainly Facebook and WhatsApp to share personal contact details of the suspected returnees, with threats of further exposure should they fail to report for testing.

It remains unclear how the public got access to the personal details of the suspected individual returnees that led to some targeted physical attack and threats of eviction and online exposure that breached the right to personal privacy of these individuals as provided for in the Data Protection and Privacy Act, 2019.

Clampdown on Opposition Rallies and Meetings

In October 2020, Uganda’s Electoral Commission (EC) issued campaign guidelines requiring candidates to ensure that their rallies do not exceed 70 attendees and to ensure they maintain a two metres distance, so as to contain the spread of the coronavirus. The number was later revised to a maximum of 200 people. Contestants were also encouraged to use the media as a primary campaign channel.

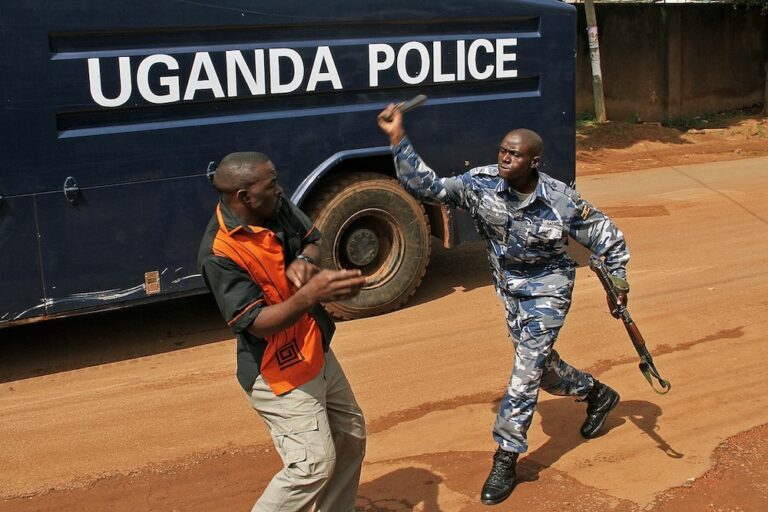

However, it has proved a challenge for contestants to adhere to the electoral body’s guidelines on the numbers of attendees. Worse still is that security agents have been accused of breaking up opposition meetings and rallies with less numbers than those prescribed in the guidelines, while turning a blind eye to the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM) party, whose candidates’ rallies and processions often gather more than 200 people.

On November 18, 2020, the National Unity Platform (NUP) presidential candidate Robert Kyagulanyi a.k.a. Bobi Wine was arrested in Luuka District where he was scheduled to address his supporters. Police accused him of having more than 200 attendees. In ensuing protests, mostly in the capital Kampala, security forces shot more than 50 people and arrested over 800 people.

Under the guise of controlling the spread of the virus, opposition presidential candidates are regularly stopped from accessing major towns and are forced to abandon their plans of campaigning in some districts, or only hold meetings in low population centres with limited voter numbers. That leaves the mass media as their main means of spreading their messages and reaching voters.

As part of efforts to discourage mass rallies, the UCC in November 2020 issued the Guidelines on the Use of Media during the General Elections and Campaigns 2021. According to the guidelines, all media stations shall not discriminate against any political party or candidate, or subject any political party or candidate to any prejudice in the broadcasting of political adverts. Additionally, all state-owned media stations, in accordance with the Presidential Elections Act, 2005, and the Parliamentary Elections Act, are required to schedule meetings with nominated presidential candidates, parliamentary candidates and other political contenders or their representatives to agree on the schedule or timetable for campaigns, and how it can be shared equitably among the contenders.

On the other hand, all private media stations are required to ensure that all their advertising space and air time is not bought out by one party. Moreover, all political parties, organisations and candidates must be given an opportunity to purchase airtime for political adverts or campaigning where they so request.

However, for several contestants, attempts to use broadcast media, especially radio talk-shows, have been frustrated as they have been denied access. In Soroti district, the FDC presidential candidate, Patrick Oboi Amuriat, was denied access to any of the radio stations. Amuriat said that radio stations including “Etop, Delta and Kyoga Veritas where he had booked for talk shows declined to host him citing intimidation from (the) government.” In Kotido, Amuriat was also denied airtime in any of the radio stations while in Agago, a radio station which was hosting him was switched off air for about 30 minutes during the show.

Kyagulanyi, another presidential candidate, was on November 25, 2020 told to leave Spice FM radio premises in Hoima City, where he was set to address residents of that area, a few minutes after his arrival. Last August, Kyagulanyi dragged the government to court for blocking his radio talk shows.

These patterns are not new. Dr. Kiiza Besigye, who contested against Museveni for the presidency in the last four presidential elections, was on multiple occasions denied access to radio airtime, with the radio stations often warned not to host him.

In 2016, the state broadcaster UBC was found by the Supreme Court, in the presidential election petition by then presidential candidate Amama Mbabazi, to have flouted Article 67(3) of the Constitution and Section 24(1) of the Presidential Elections Act. The provisions require that all presidential candidates be given equal time and space on state-owned media to present their programmes to the people.

Impact on Citizen Democratic Participation

With just a few weeks left until the January 14 election), the government of Uganda should restrain itself from further affronts on civil liberties, especially the rights to freedom of expression, access to information, assembly and association, the lifeblood of any democratic society. Efforts to combat and contain the pandemic should not be used as an excuse or tool to stifle democracy.