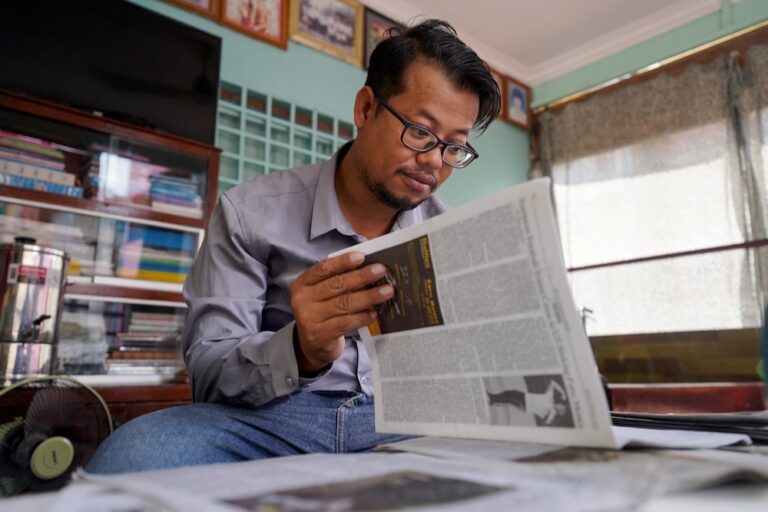

IFEX's Asia-Pacific editor Mong Palatino features the work of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights and civil society groups in promoting the empowerment of environmental activists and land rights defenders in Cambodia

The rise in land disputes across Cambodia in recent years coincided with the dismantling of opposition parties and the forced closure of independent media outlets. Amid these challenges, communities resisting displacement and development aggression have struggled hard to assert their Constitutionally-guaranteed rights. When authorities doubled down on repression, various stakeholders responded by extending solidarity to villagers and Indigenous Peoples who are defending their land and cultural resources.

Suppression of critical voices

Last July, ten members of the environmental group Mother Nature were sentenced to six to eight years in jail for allegedly plotting against the government and insulting the monarchy. Their “crime” was documenting a sewage flow from the royal palace into a river in 2021.

Reacting to the court verdict, more than 50 civil society organisations signed a statement describing the decision as a “national shame” and a “mockery of justice”. They added, “We should be honouring these activists, not imprisoning them.”

The event illustrates how laws are being weaponised to criminalise environmental advocacy in Cambodia. In the past two months, close to a hundred people have been arrested for criticising the massive Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Development Triangle Area. Even social media users have been targeted and demonised as “extremists” for articulating their concern about the grave impact of the project on the country’s territory and biodiversity.

“Please find this person and take legal action, because it is not freedom of expression.”

This was posted by former Prime Minister Hun Sen on his social media account after a Facebook user left a critical comment about the project. Predictably, the police treated it as a directive and arrested a 53-year-old woman who was subsequently charged with incitement.

Hun Sen was Cambodia’s prime minister for nearly four decades. He was replaced by his son last year but remains Senate president. Under the Hun Sen government, harassment cases were filed against independent media outlets, opposition figures were accused of conspiring with foreign powers, and major opposition parties were forced to disband. Hun Sen relied on these repressive measures to silence critics, especially those who have denounced the anomalies surrounding the land concessions awarded by the government to local and foreign corporations.

Between April 2019 and July 2023, IFEX member the Cambodian Center for Human Rights (CCHR) documented the arrest of 195 individuals, 22 of whom were convicted under various criminal charges, in connection with their land rights activism. During the same period, there were 25 instances when state forces used violence and disproportionate measures against peaceful assemblies related to land and environmental issues.

Almost half of the 33 incidents in 2021 involving press freedom violations were related to attacks against journalists reporting on land matters. In 2022, scores of people advocating for land rights and environmental protection were targeted with “strategic lawsuit against public participation” (SLAPP) suits.

In an e-mail interview, CCHR wrote to me of the worsening difficulties land rights campaigners face today.

“Local authorities impose restrictions on local land rights defenders, including tracking their movements, limiting their meetings, and suppressing their ability to speak out on their issues. These combined challenges significantly impede the ability of local land rights defenders to effectively advocate for their cause and mobilize support within Cambodia.”

Supporting community responses

When the work of media is constrained and the opposition to the ruling party is under attack, communities facing dislocation and their supporters have no choice but to step up their own work to garner public support, raise awareness, and put pressure on authorities. Despite the risk of triggering harsher state reprisals, communities have demonstrated their defiance.

CCHR underscores the connection between promoting free speech and environmental advocacy.

“Land and environmental activists have utilised their freedom of expression and right to information through peaceful assemblies, complaints, petitions, and social media to seek solutions and urge the government to protect the environment.”

Civil society groups like CCHR have amplified support to communities through trainings and workshops on the right to access information and relevant laws on environment and political advocacy.

“The trained community representatives then share their knowledge with their members, ensuring they understand their legal advocacy rights and the activities prohibited by law,” CCHR explained.

CCHR also emphasised that this knowledge empowers local communities to overcome fear and harassment in asserting their rights – including by seeking legal remedies for land grabs and the protection of encroached natural resources. If authorities attempt an illegal arrest or initiate legal harassment against individuals, “community members unite to protect them from unjust legal action.” In line with this, CCHR pointed out the peaceful advocacy of land rights and environmental defenders.

“In the event of a serious clash with state forces, we strive to maintain a non-violent approach, exercise patience, and seek a peaceful resolution to the conflict.”

CCHR summed up the work and partnership of human rights groups and community-based land rights defenders, stating:

- We empower community members by explaining their rights to freedom of expression, information, and assembly;

- We inform community members of their right to seek legal representation and social assistance from Non-Government-Organizations (NGOs);

- We communicate with partner NGOs, requesting legal consultation, representation, and social assistance;

- We issue press statements about instances of legal harassment, seeking endorsements from other relevant communities and partner NGOs, and disseminate these statements publicly; and

- We share information about cases of legal harassment with the media, enabling them to amplify our concerns and bring them to wider public attention.

After a year in power, Prime Minister Hun Manet has shown no inclination to reverse his father’s authoritarian policies. Harsh measures continue to be deployed against community activists and online critics are threatened with trumped-up cases.

This has only strengthened the resolve of civil society groups like the CCHR to remain steadfast in their call for substantial legal and political reforms at the national level, while promoting the empowerment of environmental defenders at the grassroots.

As for persecuted groups like Mother Nature, the words of one of its imprisoned members, Yim Leang Hy, carried a powerful message for fellow beleaguered green crusaders.

“Do not be discouraged, because the main intention of putting me in prison is to demoralise the youth and the people. The intention is to tell them not to care about the environment, empowerment or social justice. If we are discouraged, if my absence has an effect, if everyone is afraid, it means that evil can still happen in Cambodia. It means that our next generation will become a victim, like me and everyone else who is suffering today.”