The major challenge to the Filipino dominant media is the same today as it was under the dictatorship: defending free expression despite an ownership system that creates a conflict between the private interests of the media and the public interest of providing citizens with the information they need.

(CMFR/IFEX) – The Philippines has a long alternative press tradition that goes back to the reform and revolutionary movements of the late 19th century – from Marcelo H. Del Pilar’s Diariong Tagalog, to La Solidaridad, Kalayaan, El Heraldo de la Revolucion, and El Renacimiento. In contrast to the dominant press – conventionally and wrongly referred to as the “mainstream press” – controlled by narrow political and economic interests, the alternative press has not only been free of such entanglements. It has also been committed to the historic struggles for Philippine independence, human rights, and social and political change.

The alternative press, together with a number of individual journalists in what was then known as the “crony press,” played a significant role in the anti-dictatorship resistance from 1972 to 1986. But as things “normalized” – as the crisis seemed to wane and political stability restored – the alternative media receded into the background of Philippine events, leaving to the dominant press the task of providing the citizenry the information and analysis it needed.

Because of the political and economic interests behind them, however, the media organizations that constitute the dominant press have always been unequal to that urgent task. The major challenge to the dominant media remains the same today as it was 27 years ago: it is that of defending and enhancing press freedom and free expression despite an ownership system that creates and sustains a fundamental conflict between the private interests of the media, and the public interest of obtaining the information citizens need to discharge their duties as sovereigns in a political system that claims to be a democracy.

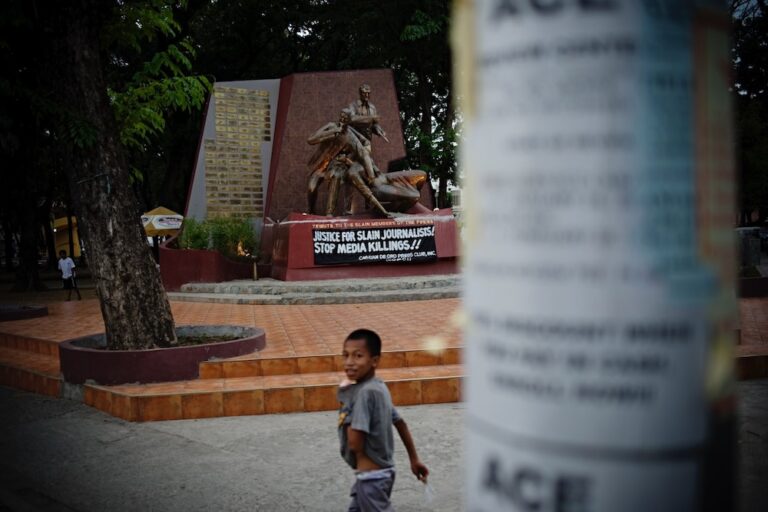

The challenge is especially severe because of a problematic media environment. The Marcos dictatorship collapsed in February 1986, or 27 years ago, but at least two bills restrictive of access to information, free expression, and press freedom became law in August and September last year. Despite a two decade campaign, the country still has no Freedom of Information Act. The killing of journalists is continuing, with 129 killed for their work since 1986. Harassments and threats including the filing of criminal libel suits based on an 82-year-old libel law to silence critical practitioners are similarly continuing.

The trial of a veritable handful of the hundreds suspected of masterminding, implementing and otherwise participating in the worst attack on the press and media in history – the Ampatuan Massacre of Nov. 23, 2009 – is proceeding so glacially some witnesses have already been killed with the same impunity as other slain journalists.

Meanwhile, corruption and personal conflicts of interest in the media have been blamed on the inadequacy of, or lack of training among, those practitioners who, it is alleged, are journalists only by accident. Impunity itself has been blamed on journalists’ lack of training – or on their being in the wrong place at the wrong time, or on their failure to scan their immediate surroundings for possible threats. But the unpleasant truth is that these problems persist because neither the fundamentals of the State nor those of the media as institutions have changed despite the overthrow of the Marcos regime in 1986.

In a pattern that has held since US colonial rule, political and economic interests with a stake in political power and commercial gain own and control media organizations. In both city and countryside, they keep practitioners in uncertainty and even poverty by refusing to regularize their employment or to pay half decent wages – or, as in so many cases in communities outside Manila, to even pay wages at all, expecting practitioners to survive on advertising commissions and even on corruption.

The numbers and the social evidence speak for themselves. Journalists whether in print or broadcast are still being killed, harassed and threatened, and in addition must contend with the added difficulties of obtaining the information on which their profession depends, and the additional perils of criminal libel over the Internet. Critical journalists have also been banned from local government press conferences, included in military “Orders of Battle,” and their organizations tagged as “enemies of the State.”

The consequence is press and media inadequacy in providing the information Filipinos need to transform Philippine society. Press freedom and free expression are explicitly protected by the Constitution on the assumption that they’re crucial to the democratic and development discourse: they are after all not their own reason for being, but only means to an end. But their full exercise, meaning in furtherance of citizen understanding of the Philippine crisis and what need to be done to address it, is hampered by both legal as well as extra legal constraints.

The challenge to the press and media if they are to be authentic participants in, and movers of the processes of national change and development is to overcome the limitations erected by a system of ownership sustained by often narrow political and business interests. The 27th anniversary of the EDSA mutiny should be, among others, an occasion for the practitioners in the dominant press and media to re-examine themselves and to find the means, despite their organizations’ primary focus on profit and political gain, to contribute to the realization of the promises of EDSA.