Facebook's removal of posts critical of Philippines president-elect and other political personalities sparks outcry.

This statement was published on cmfr-phil.org on 17 June 2016.

President-elect Rodrigo Duterte and his camp have been roundly praised for their adept social-media strategy during the campaign. He rose to the presidency, it is said, on the back of social media, whose power his team harnessed in unprecedented and highly effective ways. Perhaps it does not come as a surprise that, this early, the public is now seeing the dark side of this convergence between politics and social media.

In late May and early June 2016, after Duterte’s victory was already apparent, Facebook took down posts critical of Duterte and other political personalities, sparking an outcry not only from the journalists affected but also from other social media users.

News broke on June 1 that Facebook had deleted veteran journalist Ed Lingao’s May 24 post that criticized Duterte’s statement that he would allow the burial of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Lingao said the post was deleted for allegedly violating Facebook’s “community standards.” A follow-up post documenting the comments he received from social media users was also deleted. Lingao posted an edited version of his original post but it was also taken down. Facebook restored it later, apologizing for the “mistake.”

Lingao, however, was not the only affected Facebook user. Journalists Nonoy Espina and Inday Espina-Varona were barred from posting and commenting in their own Facebook accounts. Espina-Varona said “some other friends in the media, some artists and social activists” had also been suspended from using their account.

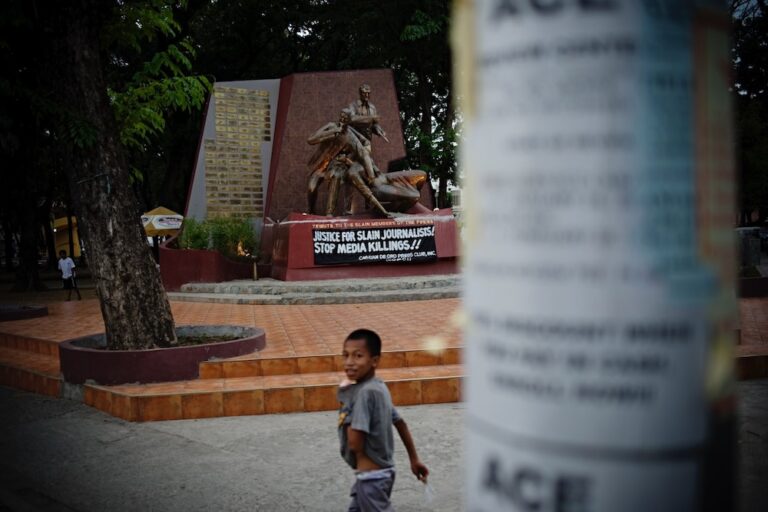

The Economic Journalists Association of the Philippines’ (EJAP) official Facebook account, Ejap Pilipinas, was also taken down on June 4 for allegedly violating Facebook’s “authenticity policy.” On June 3, prior to the takedown, EJAP released a statement criticizing Duterte’s remarks about the killing of journalists. Following its removal, the statement circulated in other social media accounts and pages, including that of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP).

Similarly, Juan Nationalist, a Facebook page that posted numerous criticisms about Duterte, was shut down but later restored after one of the page’s administrators appealed to Facebook’s Katie Harbath, outreach director for Global Politics and Government.

Keeping the Platform Safe?

In its defense, Facebook cited its “community standards” protocol as the basis for the takedown of the posts. This prohibits posts that are considered hate speech, that constitute direct threats, that tend to bully and harass, that feature violent and graphic content, that promote criminal activity, sexual violence and exploitation, dangerous organizations, regulated goods and self-injury, among others. While Facebook says it respects differences in opinions, the social network “may remove certain kinds of sensitive content or limit the audience that sees it” in the interest of the website’s diverse community.

These rules set by Facebook appear reasonable at first glance. But these have implications on the right to free expression. That the social media giant can take down a critical post by a legitimate journalist about a legitimate issue should call attention to the process used in identifying what can and cannot be allowed.

What constitutes unallowable content in the first place? What are the parameters and requirements taken into consideration by Facebook administrators in determining what should be taken down? Who are the people in charge of reviewing reported content and what are their qualifications? In Lingao’s case, which of the prohibitions did his post violate and how and why was it categorized as such?

Online Mobs

The issue of “online mobs” was brought up by some of the affected parties as well, which raised the possibility of organized attacks by groups with economic, political and other interests – in this case, supporters of Duterte and Marcos. But Facebook denied that that is what happened, while also reiterating that multiple abuse reports by users offended by these posts do not matter when they decide whether to take down a post or impose restrictions.

That denial notwithstanding, Facebook needs to make clear how it wields its immense censorship powers. Surely, it is not an accident that posts critical of Duterte and Marcos were the only ones taken down. This suggests, again, that online supporters of the two politicians flexed their collective muscle– and Facebook took notice.

In any case, as AlterMidya – a network of independent and progressive media outfits, institutions and individuals – put it, the actions of Facebook are “disturbing” and should be of concern, as they indicate that the social network can “summarily censor certain posts, especially those of a political or journalistic nature, without due process…”

This is certainly not going to be the last time incidents like this will happen, and that brings up a lot of anxiety among the media community, especially since we have a president-elect who doesn’t hide his disdain for the press. That Duterte even appointed as spokesman Ernesto Abella, one of his social media volunteers during the campaign, is telling. What would this mean for journalists who use and value Facebook as an extension of their journalistic platforms?

The takedown incidents bring to the fore a possible media censorship issue, even if Facebook is, strictly speaking, not a media outlet in the usual sense but a community of users. Still, the fact that journalists and media companies have been gravitating to the popular social network because of its reach and influence does make attempts to silence journalists and users on Facebook a serious freedom of expression issue.