September saw protests and internet disruptions in Togo and Cameroon, an initiative to increase gender diversity in Nigeria's tech and media community, and an access to information report that could help countries work towards the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.

Gender in focus: The Naija Data Ladies

Sometimes the news doesn’t make sense until we see the numbers. Whether we’re learning about the magnitude of a drought, the rapid increase in literacy rates of a certain region, or the differences in pay between men and women, the public needs access to accurate, easily digestible data in order to fully grasp current events.

This is why an initiative like the Naija Data Ladies – a network of women data journalists in Nigeria – is so important. According to IJNET, the network was established in April 2017, with the goal of producing data-driven news stories on development and health issues across Nigeria.

Jacopo Ottaviani, who guided the creation of the Data Ladies Network, told IJNET that the inspiration for the project came from Chicas Poderosas, a project that seeks to empower women in digital media in Latin America. Ottaviani and his colleagues were also excited by “the idea of building the capacity and skill sets of journalists already working in Nigerian newsrooms, who can then disseminate the culture of data to their colleagues.”

“Being a part of the Naija Data Ladies team has made me a better data cruncher for the benefit of our audience,” Data Ladies team member Bukola Adebayo told IJNET. “I’m able to break down complex data in a way that makes it more relevant and applicable to our audiences’ lives and engages them in new ways.”

Operation censorship

On 12 September, soldiers in Umuahia, Abia state stormed the Nigerian Union of Journalists press centre, beating up journalists and seizing their equipment.

According to RSF, the attack came after reporters had documented Operation Python Dance – a military procession intended to show its dominance over People of Biafra, a local separatist group.

Local army commanders eventually apologised for the raid. But Clea Kahn-Sriber, head of RSF’s Africa desk, noted that remorse would be better replaced with preventive measures and education. “Instead of reacting after the event, the Nigerian government should make an effort to train the security forces about the role of journalists in society and thereby foster better relations between two sectors that are essential in a democracy.”

In Somalia, however, it seems like no level of training will lessen the amount of violence that journalists experience on a daily basis.

Somalia loses yet another journalist

On 10 September, a suicide bomb exploded at a cafe in Beledweyne, Somalia, killing at least 3 people and injuring 10 others, including reporters. News reports cited by CPJ state that militant group Al Shabaab claimed responsibility for the attack. 24-year-old reporter Abdullahi Osman Moallim died four days later from head injuries sustained in the bombing.

Sources told CPJ that Moallim and his colleagues had been at the restaurant waiting for a press conference that was scheduled at Hiiraan governor’s office nearby.

“Condemning this killing is not enough – authorities must do more to catch murderers who masterminded this heinous crime and deployed the suicide bomber” reads a joint statement issued by The National Union of Somali Journalists (NUSOJ) and the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ).

Age limits and parliamentary brawls in Uganda

Lawmakers, journalists and protestors alike have faced violence as lawmakers introduced a constitutional amendment that would remove the presidential age limit in Uganda.

President Yoweri Museveni – who has been in power since 1986 – is 72 years old. The age limit for presidents is 75, which means that under the current law, Museveni will not be able to run for another term in the 2021 elections. His supporters are looking to change that.

The Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) reports that on 20 September, police detained five journalists who were covering a press conference a group called Youth Against Dictatorship, which was protesting the constitutional amendment on the age limit. The police also confiscated their recording devices. One of the journalists told HRNJ-Uganda that police interrogated them on who mobilized them to cover the press conference. The journalists were eventually released and their equipment was returned to them.

A few days later, a brawl broke out in parliament as the bill was debated. According to Al Jazeera, “MPs brandished microphone stands, threw punches and clambered over benches as security officers sought to remove 25 legislators barred by Speaker Rebecca Kadaga…”

Protests that broke out on the streets over the bill were also met with tear gas in Kampala, according to Al Jazeera.

Journalists not terrorists

Ahmed Abba has become a household name in the free expression community for all the wrong reasons. In fact, the correspondent for Radio France Internationale’s Hausa service was recently named an honoree of CPJ’s 2017 International Press Freedom Awards, to be held on 15 November. Earlier this year, Abba was sentenced to ten years in prison in Cameroon on charges of “laundering the proceeds of a terrorist act” after reporting on activities by extremist group Boko Haram.

If CPJ’s new report is any indication, Abba is not the only journalist who will spend years of his life behind bars for doing his job. On 20 September, CPJ published Journalists not terrorists: In Cameroon, anti-terror legislation is used to silence critics and suppress dissent. The report shows that Cameroon’s anti-terror law is being used against reporters who simply report on Boko Haram, or on civil unrest in the English-speaking regions of Cameroon.

“When you equate journalism with terrorism, you create an environment where fewer journalists are willing to report on hard news for fear of reprisal,” said Angela Quintal, CPJ Africa Director and author of the report. “Cameroon must amend its laws and stop subjecting journalists – who are civilians – to military trial,” Quintal added.

Legislation is not the only tool being used to silence Cameroonians; limiting internet access is another.

On 30 September, activists in Cameroon’s anglophone areas began having trouble accessing Facebook and WhatsApp. According to Quartz Africa, activists in the state of Southern Cameroons/Ambazonia had been planning protests for 1 October to call for the independence of their region, which existed as its own entity prior to the unification of Cameroon.

Earlier this year, residents of Cameroon’s anglophone North-West and South-West regions endured a 93-day internet shut down, prompting international outcry and a campaign called #BringBackOurInternet.

In neighbouring Togo, internet access was not much better.

West Africa’s fear of Facebook

On 5 September, 3G service was disrupted in Togo; Facebook and WhatsApp were completely inaccessible on mobile applications. The following day, internet connectivity via cable was also disrupted, according to information obtained by the MFWA.

The disruptions come as the Togolese opposition coalition organised countrywide demonstrations demanding political reforms and protested police brutality that occurred at demonstrations the month before.

It’s no surprise, then, that Togo is among the countries being closely scrutinized by the MFWA in a report about internet access.

In September, the MFWA released the first edition of the West Africa Internet Rights Monitor. The report covered the period of April-June, 2017 and examined online access in Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Ghana, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, The Gambia and Togo. Some of its findings include a lack of effective internet-specific legal frameworks, inadequate infrastructure and a high cost of data within West Africa.

Access to information across Africa

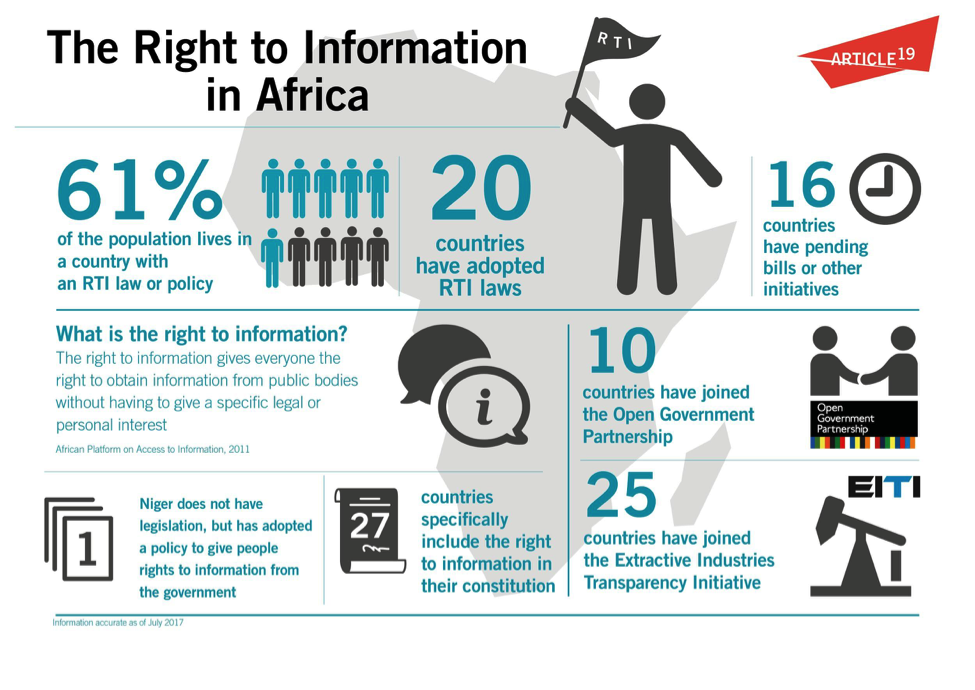

Conversations about internet access did not stop in West Africa; they featured prominently in initiatives launched by IFEX members across Africa in celebration of UNESCO’S International Day for Universal Access to Information (IDUAI), on 28 September.

For example, ARTICLE 19 created an infographic which shows “where right to know laws are in place, where governments are making commitments to transparency bodies, and where there’s still room for progress” across Africa. The infographic is also available in French.

Media Rights Agenda (MRA-Nigeria) hosted “FOI Week” from 25 to 28 September, 2017, which featured social media engagements on different FOI topics including citizen usage of the FOI Act, FOI and the media, and FOI and corruption. If you missed it, you can still engage with the three-day conversation by following this hashtag: #MRAFOIWk17.

Media Rights Agenda @MRA_Nigeria will be celebrating the #IDUAI2017 with its “FOI Week” from September 25 to 28, 2017. #MRAFOIWk17 pic.twitter.com/gVLXScOZQz

— Media Rights Agenda (@MRA_Nigeria) September 23, 2017

Ugandan opposition lawmakers fight with plain-clothes security personnel in the parliament while protesting a proposed age limit amendment bill debate to change the constitution for the extension of the president’s rule, in Kampala, 27 September 2017REUTERS/James Akena

ARTICLE 19