How do you fix a national intelligence system no one understands?

This statement was originally published on eff.org on 24 October 2016.

This post is part of the series “Unblinking Eyes: The State of Communications Surveillance in Latin America,” a collaborative project conducted with digital rights partners in Latin America, which documents and analyzes surveillance laws and practices in twelve countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Peru, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, and Uruguay. In addition to the individual country reports, EFF produced a comparative legal analysis of the surveillance laws in those twelve countries, as well as a regional legal analysis of the 13 Necessary and Proportionate Principles written with Derechos Digitales, and an interactive map that summarizes our findings.

In Peru, weak surveillance oversight brought down a prime minister. In 2015 the Peruvian magazine, Correo Semanal, alleged that Peru’s National Intelligence Directorate (DINI) had illegally spied on journalists, businessmen, policy makers, politicians, and members of the military and their families. The DINI purportedly accessed information stored in Peru’s national registry of properties.

The then Peruvian prime minister, Ana Jara, who was responsible for overseeing the DINI at the time, argued that the directorate was simply “copying information contained in public files and not violating tax secrecy or personal privacy.” Even so, Ms. Jara asked the Prosecutor’s Office to investigate the situation for criminal wrongdoing and fired the agency’s director, its’ counter-intelligence chief, and its’ national intelligence chief.

Congress felt the prime minister was to blame. Due to the political context at the time—for the upcoming presidential and congressional elections were only a year away—a Peruvian congressman argued that it was “obvious that the real goal [of the DINI’s data collection] was to filter information to the press in order to ‘eliminate’ the ruling contenders [for the upcoming elections].” Then-President Ollanta Humala was left to select a new prime minister and cabinet after Ms. Jara was forced to step down.

President Humala did little to heed Congress’s warning about unchecked surveillance of those in power. Just four months after Jara was ousted, the president enacted Legislative Decree Nº 1182, dubbed “Ley Stalker,” which forces telecommunications providers to retain communications data of their users for three years. Simply put, the decree shifted surveillance practices based on individualized suspicion to the mass, untargeted collection of communications of an entire population. Ley Stalker also allows warrantless access to location data in cases of blatant crimes.

Ley Stalker and the DINI are just part of a continuing patchwork of poor surveillance oversight and alleged misuse by the executive in Peru. You can hear more about that history from those who experienced it, in our video below.

To learn how to fix these problems, Peru’s leaders need to understand how their current system works—and what needs to be done to fix it.

Surveillance in Peru Today

The “State Communications Surveillance and the Protection of Fundamental Rights in Peru,” by Miguel Morachimo, director of the Peruvian NGO Hiperderecho, is part of the project “Unblinking Eyes: The State of Communications Surveillance in Latin America.” The Peru report analyzes surveillance law in Peru and provides recommendations. Here are some of its main findings:

On Peru’s Culture of Secrecy: In October 2015, Hiperderecho filed a freedom of information request to obtain the regulations that control the collaboration between the private sector and the government. Essentially the NGO was seeking the document that allows Ley Stalker to function. Hiperderecho’s request was denied; the government has kept this protocol secret from the public, categorizing it as “reserved information.”

On Location Privacy: Peru requires a judicial authorization for every interception of private communications, and courts have interpreted this requirement so that it is applied broadly. However, Legislative Decree Nº 1182 grants the National Police warrantless access to location data in real time, without a court order, in cases of blatant crimes. Hiperderecho argued that in such cases, a judicial authorization prior to the investigation should always be a constitutional requirement. The system like the one described in Legislative Decree Nº 1182 represents a shortfall in the guarantees of the right to privacy of all Peruvians. Peru’s lack of strong legal protection for location privacy must change.

On User Notification: Laws in Peru require that anyone affected by surveillance be notified. However, notification only occurs after an investigation closes. Peru allows the user to seek judicial re-examination of the surveillance order.

On Mandatory Data Retention: Requiring telecommunications companies and ISP’s to store data of an entire population is inherently a disproportionate measure. Adding insult to injury, the safeguards for the type of data to be retained are not clearly defined by law. Peru should repeal Legislative Decree Nº 1182, and reconsider the need to tie evidence to a place or persons in order to authorize any surveillance measure.

On Law vs. Practice: It is necessary for the legislation that applies to intelligence activities to be clear and detailed in order to establish a limit to the scope of intelligence activities and tasks. Regulations must specify what the intelligence collection activities are, and indicate the time period in which the collected information shall be destroyed, or the criteria under which it shall be shared with other institutions or foreign states. Peru must ensure that any written norms are translated into consistent practice and that any failure to uphold the law is discovered and remedied.

On Public Oversight: Finally, it is necessary for Congress’s Intelligence Commission to have more autonomy. This commission is the independent body with the greatest capability to control intelligence work. Nonetheless, little is known about its work, since the meetings and decisions are confidential. Thus, transparency obligations could be imposed on the commission without weakening its functions, so that it reports on the number of times its members or special judges are summoned and on the number of special procedures that have been conducted for information collection. These reports should be available to the public for auditing purposes.

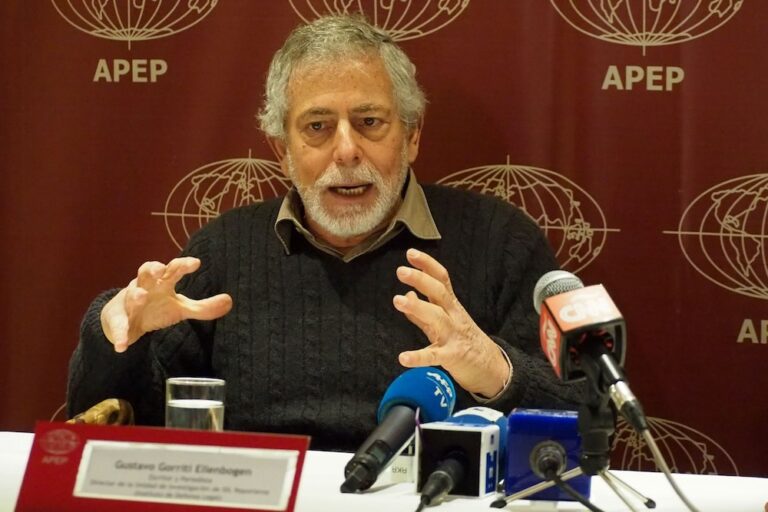

Overall, Miguel Morachimo of Hiperderecho is concerned with the lack of transparency and accountability of the intelligence system:

“Few things can be said with certainty about how to reform our national intelligence system mainly because no one really knows how the system has been working over the past ten years. This is precisely the first thing to fix. The national government should be more transparent about the scope of their intelligence work, the number of data requests it makes, and the kinds of information it obtains from Peruvians through intelligence channels. This isn’t about tipping off the bad guys, this is about allowing the public access to anonymized statistical information about their operations in order to ensure that those in power are properly overseen and held accountable.”

Peruvian politicians have already seen the consequences when surveillance grows out of hand; but it seems the temptation to grant greater powers without oversight remains. As with every country in our reports, the politicians and judges of Peru should understand that without careful limits, broad mass monitoring powers will ultimately undermine the safety of their own positions, and the human rights of the people of Peru.