(CMFR/IFEX) – The following is a statement by Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, Inc. (FFFJ), of which CMFR is a member: Primer on the Marlene Esperat case trial Prepared by the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, Inc. (FFFJ), June 23, 2006 Who is Marlene Esperat? Marlene Esperat was a columnist for Sultan Kudarat paper The […]

(CMFR/IFEX) – The following is a statement by Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, Inc. (FFFJ), of which CMFR is a member:

Primer on the Marlene Esperat case trial

Prepared by the Freedom Fund for Filipino Journalists, Inc. (FFFJ), June 23, 2006

Who is Marlene Esperat?

Marlene Esperat was a columnist for Sultan Kudarat paper The Midland Review. She also had a stint as a block-time radio broadcaster. Popularly known as “Madame Witness” because of her public service media exposés, she was also elected president of Region 12’s Tri-Media Association by her peers.

During her employment in the Department of Agriculture (DA) Region 12 from 1987 to 2004, she uncovered numerous cases of graft and corrupt practices allegedly committed by public officials, involving rampant misuse of public funds intended for the use of marginalized farmers.

She accused Osmeña Montañer and Estrella Sabay, Region 12 Finance Officer and Regional Accountant, respectively, of being “corrupt” DA officials. Esperat worked on numerous cases, such as the unremitted government’s share of GSIS premiums of DA 12 employees from January to December 1997.

Esperat, along with several witnesses, also exposed the allegedly deliberate burning of a DA office in Cotabato City on May 7, 1998, to destroy the hard evidence in the cases against Montañer and his companions.

In early 2005, Montañer and Sabay purportedly drew up a plan to permanently silence Esperat, through ex-military intelligence officer Rowie Barua. On March 24, self-confessed killer Gerry Cabayag fatally shot Esperat in the head in front of the journalist’s shocked children, while they were at supper.

Esperat completed a degree in Chemistry in Iloilo, where she met her first husband, radio journalist Severino Arcones, in the early 1980s. Arcones was a hard-hitting commentator who lambasted local government officials in the province. He was killed in 1989 for his work as a journalist. It was Arcones who stirred Esperat’s interest in using journalism as a tool to fight corruption in society.

Prior to commencing her work as a journalist in 1999, Esperat worked as a chemist and later as a resident ombudsman for the DA. While inside the DA, Esperat discovered that the fertilizers that the regional office were giving to the local farmers were insufficient, inferior, and far cheaper than what was originally listed in the official budget of the department.

Frustrated by the country’s slow due process, Esperat turned to the power of the pen and airwaves to expose her bothersome discoveries, which, in turn, led to her brutal death.

Why is this case significant?

“Unlike in the other slain journalists’ cases, this one [the Esperat case] seems to have a very promising outcome as there is a clear identification of the masterminds and full cooperation from the witnesses,” said private prosecutor Attorney Nena Santos.

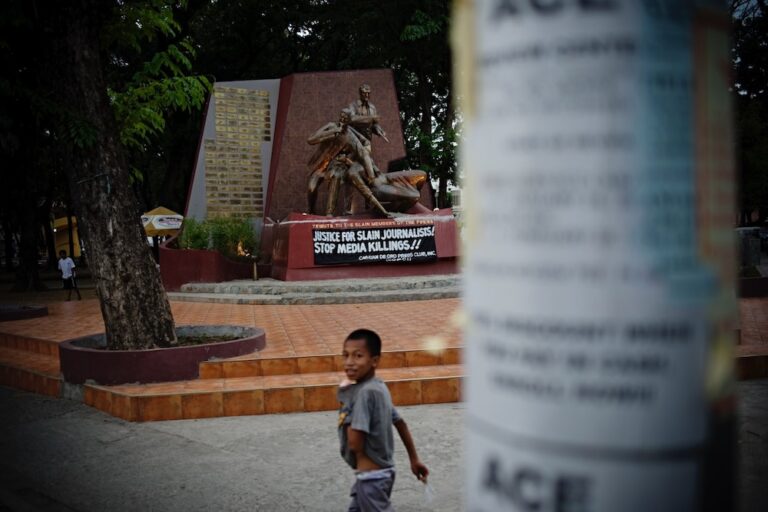

Since 1986, 59 journalists have been killed in the line of duty. Not a single mastermind has been successfully prosecuted in any of these cases.

To date, there are only two convictions – in the cases of Nesino Paulin Toling and Edgar Damalerio. Toling’s family, however, proclaims that the killer was just a “fall guy”. Until now, there has been no indication of the identity of the real author of, or of the motive for, the murder.

In the Damalerio case, it was clear from the outset that ex-policeman Guillermo Wapile was the one who gunned down the Pagadian-based journalist. Eights months have passed since Wapile was convicted by a Cebu City court, but everybody remains in the dark about the real motive behind Damalerio’s slaying, and more so on the question of the possible mastermind behind the crime.

In contrast, the Esperat case marks the first time that a real mastermind (in this case, two) can be pinned down.

With the strong testimonies of suspect-turned-state witness Barua and consistent pressure from media organizations, both local and international, the cases against masterminds Montañer and Sabay remain strong.

The success of the Esperat case trial may very well hinge on the involvement and successful prosecution of the suspected masterminds, as this will prove that the government and the justice system are still steadfast in bringing a real resolution to the continued attacks against the country’s battered press freedom.

Moreover, the issue is not only one of press freedom. Montañer and Sabay’s connection to the killing of Esperat and the cases left by the journalist could pave the way for deeper scrutiny into the alleged massive corruption inside the DA up to the highest posts. Based on the exposés made and cases filed by Esperat with the Ombudsman when she was still alive, the corruption inside the DA not only involves the two suspected masterminds of her murder, but also several high-ranking national officials involved with the so-called multi-million peso fertilizer scam.

What is the status of the case?

Barely two weeks after the killing of Esperat, suspect Randy Grecia surrendered, and identified his three companions – Barua as coordinator, ex-Sgt. Estanislao Bismanos as lookout and Jerry Cabayag as gunman.

An amended murder complaint was filed against two of the suspected masterminds, DA Region XI employees Sabay and Montañer as additional accused, on April 15, 2005.

A Department of Justice (DOJ)-formed prosecution panel – led by Cotabato City prosecutor Tocod Ronda, a known ally of Montañer – endorsed the dismissal of charges against the two officials on June 29, 2005. A month later, DOJ reorganized the prosecution panel, now excluding Ronda, and eventually re-filed the murder charges. Ronda was later sacked from his Cotabato City prosecutor post.

On July 4, 2005, Bismanos, Grecia, and Cabayag all pleaded guilty. Barua, on the other hand, turned into a state witness.

Last August 31, the judge originally handling the case, Francis Palmones of the Tacurong City Regional Trial Court, dismissed the murder charges against Montañer and Sabay, despite the strong testimony of Barua and the support of the DOJ.

In a resolution dated November 23, 2005, the High Court approved the transfer of the case from Tacurong to a safer, more neutral court in Cebu City – the city where the Damalerio case and, just recently, slain photojournalist Allan Dizon’s case, were resolved in a span of less than two months.

The case, as earlier noted, was previously tried in a Tacurong, Sultan Kudarat court, but was transferred to Cebu through the endorsement of the Supreme Court, which, in turn, acted upon the requests of the family and the FFFJ to move the trial to a more neutral location.

Esperat’s head legal counsel, Attorney Nena Santos, said they were expecting a favorable trial, despite enduring several setbacks before the case’s transfer to Cebu.

The trial in Cebu City started last February 15 under Regional Trial Court Branch 21 Judge Eric Menchavez. It started on a low note as Menchavez rejected the motion filed by the prosecution to reconsider the dismissed murder charges against suspected masterminds Montañer and Sabay.

The first formal hearing took place last April 2-5. It involved testimonies made by a CIDG police investigator, Esperat’s son Kevin George (who positively identified Cabayag as the triggerman), and daughter Rynche Arcones (who narrated the events prior to the killing). Rynche told the court about the cases filed by her mother before the Ombudsman and the difficulties they have been facing without their mother.

The next marathon hearing was held just a month ago, from May 22 to 25. A police inspector told the court that the extra-judicial confessions made by the suspects under police custody were done without coercion and were not extracted with compulsion – indicating that all their confessions and admissions to the killing of Esperat were made of their own free will and volition.

Both the ballistic expert and firearm examinations officer reported that the pistol used to kill Esperat on March 24, 2005 was the same pistol recovered eight days later during a motorcycle accident that involved Cabayag, the triggerman.

But the highlight of the hearing was the presentation of Barua at the witness stand. The lengthy direct examination made of Barua (and the revelation he openly told in court from May 23-25) strongly refuted the defense’s argument that he and Sabay were mere acquaintances.

Barua told the court, in detail, how he was asked by Montañer and Sabay to plan and undertake the killing of Esperat – a period of more than two months from the planning stages early 2005, to the point of hiring Bismanos and company to “silence” the journalist, up to the time of payment.

For the whole exercise, it was very apparent that the prosecution had succeeded in telling the judge that Barua indeed was the vital link between the killers and the mastermind and that the motive of the murder goes beyond the money received by the killers.

What to expect and what could the media do to support the case?

The next marathon hearing is set for June 26-30, in which the prosecution will present at least six more witnesses to further augment the case and convince Menchavez to reconsider the charges against Montañer and Sabay.

The main concern for the coming marathon hearing is whether Menchavez will finally reconsider the case against Montañer and Sabay, and possibly order arrest warrants against the two, in view of the strong testimonies made by Barua. A source inside the Supreme Court recently revealed that Menchavez has a habit of not reconsidering cases previously held by a court of similar level.

Arguably one of the key factors for the case to be successful is the consistent coverage by both the national and local media. If we make our presence felt inside the courtroom, it will send a strong message to the court and the accused that the whole country, through its media entities, is closely watching the case. It would also show that the media are hell-bent on ensuring that justice is done for the courageous heroine-journalist.

Making room for this story in news dailies and network news programs will help put constant pressure on government entities and the justice system to end this culture of impunity.